The following interview is part five of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Becoming the Harvest

On a grassy field glistening with dew

the doe chose to give in to gravity.A frequent guest.

One I fed greens and carrots

whenever the ground

was snow shrouded.I discovered her one morning

quiet, composed,

her legs extended,

her neck stretched in repose.For her, dying was as natural as living.

As natural as lying down.Can it really be this simple?

Will my animal body know what to do?When my time comes, will I sing

lay me down, lay me down under the apple tree?

Reprinted with permission from

Becoming the Harvest

(Caitlin Press, 2024).

Rob Taylor: In the first stanza of the opening (and title) poem in Becoming the Harvest, excerpted above, a doe chooses “to give in to gravity.” Death is not something done to the doe as a powerless recipient, but an active choice. This feels like an important introduction to the book’s larger themes, especially to the story of your sister Suzanne’s death. Could you tell us a little about your choice to open the book in this way?

Pauline Le Bel: It just seemed right to give the reader—from the beginning—a glimpse of how I have come to view death. Not as the enemy, not as a tragic interruption to life, but as a natural part of life that follows old age. Death as a reminder to live life as thoughtfully and lovingly as possible.

I had observed the doe over several years. She had lived a good life, chomping on the flowers in my garden, birthing several spotted fawns, giving me and my friends the pleasure of her gentle presence. She knew it was time to lay down and go back to the land. I hope my animal body will also know when that time is near. In another poem, “The Angel of Death,” I ask if death might arrive in the form of an elegant angel, dressed in fine Italian leather shoes, tapping you on the shoulder, asking you for the last dance. As a dancer, I fancy that idea. It’s much more interesting to me than the image of the Grim Reaper. You get to say yes.

I remember hearing one woman say: “Here comes Pauline, she’s going to try to get us to sing,” as she left the room! These days, someone might say: “Here comes Pauline, she’s going to try to get us to talk about death.”

Pauline Le Bel

RT: In Becoming the Harvest you look at aging from a variety of perspectives. Aging feels gradual and gentle, but also turbulent: a source of power. The aging women in these poems take on the same characteristics, graceful and forceful at once. Could you talk a little about how you see these two energies come together in the aging process?

PLB: Wow! I’m delighted you picked up on that, Rob. Over the past 25 years, I’ve been writing books, poems, songs and plays to reframe what it means to be an old woman in this culture. It didn’t look too appealing to me, so I researched other cultures to learn from their perspectives. I discovered that in ancient matriarchal societies, old women—“crones”—were honoured. My first CD was called, Dancing with the Crone, a reclamation of the fierce and thoughtful energy of old women. On fire with these ideas, I gave “Kiss the Crone” workshops in the U.S. and Canada, helping women find grace, acceptance, and even joy as they aged.

One of the songs I wrote was inspired by a Hopi prophecy: “When the Grandmothers Speak, the World will be Healed.” In the song, I encourage old women to lift up their voices and weave a new world: “Love’s your needle, truth your thread.” I also sing about the Grandmothers on the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires who appeared every day at noon to demand the return of their grandchildren who were kidnapped and illegally adopted during the 1976-1983 military dictatorship. They were graceful and forceful.

Gracefulness and forcefulness do not necessarily come together as one ages. I think one must have the courage to see life as it is, to become comfortable with uncertainty, and to be determined to do something about what needs to change. Holding what might seem unbearable and allowing ourselves to find the beauty, joy, and humour that are also there.

RT: In “The Harpy,” you compare an aging woman to a harpy whose “breasts fill with honey” and whose “mind swells with possibility,” then add that the Greeks were “afraid of old women. / Rightly so.” Why do you think we should be afraid of you, Pauline? And is it a good fear? A productive one?

PLB: Ha! That harpy poem was so fun to write because it contradicts everything I was taught to be, which is nice, declawed and quiet, very quiet. Her breasts are not filling with milk, as she is much too old. They are filling with honey to sweeten life. Oh yeah, the Ancient Greeks were very afraid of old women. Our culture is too, in many ways, which is why so many older women are medicated, tranquilized. This is such a suppression of strength and wisdom.

Imagine my delighted surprise when I attended my first Squamish Nation ceremony fifteen years ago. As it came time to approach the spectacular buffet table, I was nudged forward. Elders eat first, I was told. In most Indigenous cultures, Elders are honoured. They are the repository of knowledge, living libraries.

People might experience some kind of fear or trepidation when an old woman dares to tell the truth, to start a difficult conversation, to talk about something we all try to avoid. When I was in my middle years, I created many events and opportunities to get people singing: solstice celebrations, vocal playshops, even singing at Board meetings. I had experienced how singing, making music, changes the room, changes people’s hearts and minds. Not everyone approved of this. I remember hearing one woman say: “Here comes Pauline, she’s going to try to get us to sing,” as she left the room! These days, someone might say: “Here comes Pauline, she’s going to try to get us to talk about death.” I guess it can be a productive fear, if people acknowledge the fear and have the courage to move through it.

Humans didn’t invent music, it’s ancient and wild.

Pauline Le Bel

RT: Becoming the Harvest features a suite of “lesson” poems, in which you describe important people from your life and suggest lessons that they gave you, directly or indirectly, on how to live a good life. (From Aunt Pauline: “A good life can be flashy and brief.” From the “old country woman” Marta: “Hard work never hurt anyone, / thinking about it did.”) This book feels like both a gathering of those life lessons and an offering of your own. Could you talk about those dual motivations: to record lessons you’ve received and to pass on lessons of your own? Did each motivate you to the page equally?

PLB: Thanks for noticing my appetite for learning. I find lessons everywhere, especially in nature. I don’t believe my loved ones were giving me lessons directly; I learned from the way they responded to life, dealing with hardship through humour and grace. (I hope I was able to capture their humour.) I may not even be conscious of the learning until much later. If the reader plucks a lesson from one of my poems, well, that’s a bonus.

I’ve been fortunate to live my entire life as an artist. No day job, unless you count caring for two children (a day-and-night job). I believed my job as an artist was to look at the world, see how things were, and imagine other possibilities. I even created a little jingle for myself: Reclaim, reframe, rename, without shame. It comes so easily to me. Sometimes my new perspective can be a bit idyllic and perhaps unreachable, but I carry on anyway.

In my book, Becoming Intimate with the Earth, I share the lessons I learned from Joanna Macy, Buddhist teacher and environmental activist, and Brian Swimme, physicist and cosmologist, as well as from the trees and mountains of Bowen Island. My fourth CD, Rescue Joy, is a compilation of songs I wrote a few years after my sister died. Songs full of lessons learned while my heart was breaking.

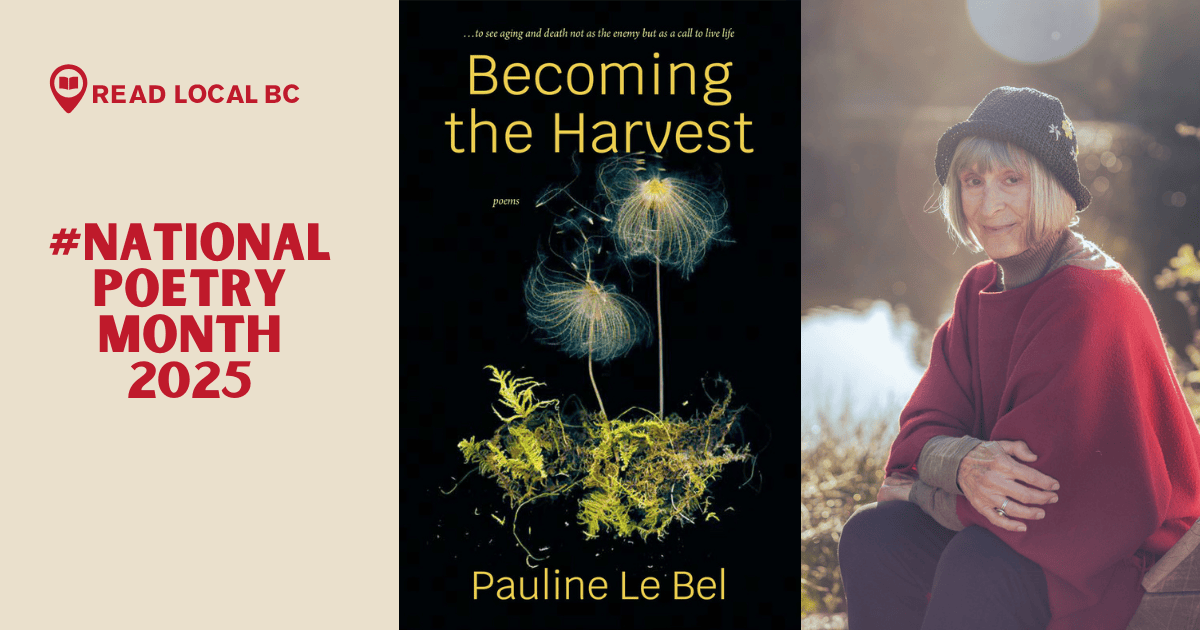

The most important lesson I learned from my elders is that aging is about going to seed—seed for the next generation. Seeds that contain lessons for the young ones about how to live a good life. For the cover of Becoming the Harvest, I chose a powerful image created by a young artist and friend, Julya Hajnoczky. It’s a Mountain Aven—a lovely white-petalled flower—going to seed. That’s how we become the harvest. That’s what I aspire to. I’m an ancestor-in-training.

Rhythm, tension and silence are essential to both song and poem… I want to feel that frisson, find the music in the poem.

Pauline Le Bel

RT: As we’ve been discussing, you are a celebrated musician with five albums to your name. Your first poetry collection was even called They Ask Me Why I Sing So Loud! I’m curious how your music has shaped your approach to poetry. In Becoming the Harvest, you write that Jacques Brel taught you “to sing with the blood rising inside me.” How would you say that lesson translates to poetry?

PLB: As a student of music for over 65 years, I’ve experienced a deep initiation into the magical world of sound that exists everywhere in the universe: wind, whales, birds, even black holes emit sound. Humans didn’t invent music, it’s ancient and wild. And Jacques Brel—another flashy, brief life— knew that better than most singer/songwriters.

You could say music was my mother tongue. Music and poetry are completely intertwined, and they have always been a part of my life. As a child, I sang Gregorian chant in the church on Sunday mornings before going back home to sing romantic French love songs in the living room. I was experiencing the spell cast by melody and rhythm long before I received a Bachelor of Music in Voice and Piano. Song has been my medicine. Music and poetry have pulled me through many a dark night. I enjoy improvisational singing on my daily walks. It’s good training for living with uncertainty. Singing without a net. You make it up as the spirit moves you. I approach writing a poem in the same way.

“The Song Spinner,” my screenplay for a Showtime movie of the week in 1995, was a fantasy that allowed me to imagine my worst nightmare: a world without music. In the Land of Pindrop, music is forbidden. Zantalalia, an old gypsy woman, banished to the Water World when she refused to stop singing, returns to Pindrop to teach young Aurora the truth about music and pass on the gift of singing. People loved this story, so I wrote three other versions, each slightly different: a novel for young readers, a CBC radio drama (I played Zantalalia, which was a blast) and a play for Vancouver Youth Theatre.

Rhythm, tension and silence are essential to both song and poem. I also write poems with the blood rising in me. I want to feel that frisson, find the music in the poem. Otherwise it becomes an intellectual endeavour. Pleasing, perhaps, but without soul. I rarely write a decent poem from a prompt.

RT: How has performing your music (as Zantalalia or otherwise!) influenced your approach to poetry?

PLB: When I was in my thirties, I took on the persona of Edith Piaf in theatre productions across the country. I worked hard to evoke the nuance, the contradictions, the essence of her character. In writing poems about the loved ones I admired, I looked for the same contradictions: their gentleness, their fierceness, their graciousness and their humour. Performing these poems adds another element. I’ve been recording them in the little studio up the hill, with my cello player, Corbin Keep, laying down some exquisite melodies. When I listen to them afterwards, I hear what’s working and what isn’t. I also pay attention to how Corbin is interpreting them and make a few revisions. I think the poems are better for it.

The most important lesson I learned from my elders is that aging is about going to seed—seed for the next generation.

Pauline Le Bel

RT: While most of your poems are closer to a page in length, some (such as “Crickets” and “Memories”) are very short, minimalistic offerings. What drew you to writing these shorter poems?

PLB: When you get older you know you have less time left. So short poems become desirable. It’s the same reason old people don’t buy green bananas, I guess.

RT: Ha! Becoming the Harvest closes with an essay, “Zig-Zag Bridges,” about your sister Suzanne’s decline and death from ALS. Why was it important for you to explore this subject in prose, instead of poetry? What did the essay form open up for you in exploring the story of your sister’s final years?

PLB: Caring for my sister Suzanne took place over almost two years. Prose gave me the spaciousness to hold the experience, to contemplate, to include her voice, and the deepening of our relationship. It was such an intense time, an intimate dance with her gradually aging body and the eventual letting go. It was my primary education in watching a life end and being surprised by the beauty of it.

The essay form gave me more flexibility to include the humour that Suzanne and I experienced as we lived through the more difficult moments. It was such a blessing to spend that much time with her again while I was writing, calling up memories of her courage, her love, reminding me it is possible to simultaneously hold joy in one hand, sorrow in the other. I suppose I could have written a suite of poems but that never occurred to me. After the essay, I return to poetry to conclude the book with one last poem, “Blessing the Body.” I needed the lyrical, chant-like quality of poetry to say goodbye.

Pauline Le Bel is an award-winning novelist, Emmy-nominated screen writer, playwright, poet, journalist, actor, singer/songwriter with five CDs of her original songs. She has previously authored two non-fiction books, Becoming Intimate with the Earth (Collins Foundation Press 2013), Whale in the Door, an environmental and spiritual history of Howe Sound (Caitlin Press 2017), and a poetry book, They Ask Me Why I Sing So Loud.

Rob Taylor’s fifth poetry collection is Weather (Gaspereau Press, 2024). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews on his website.