The following interview is part three of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

excerpt from “A&Ws”

we will conjugate surprise in each of the hundred

cardinal directions to imply her

body occurring to and in a world and otherwise

Her sobbing for example and me consoling

no one would ask how it shook my hand

let alone the air in the hallway they shared

Puke and no paraphernalia

one of those never settled

As property grew they moved

forever to outside edge of the fence

even after they were out of sight

of bend in the river they

liked so much

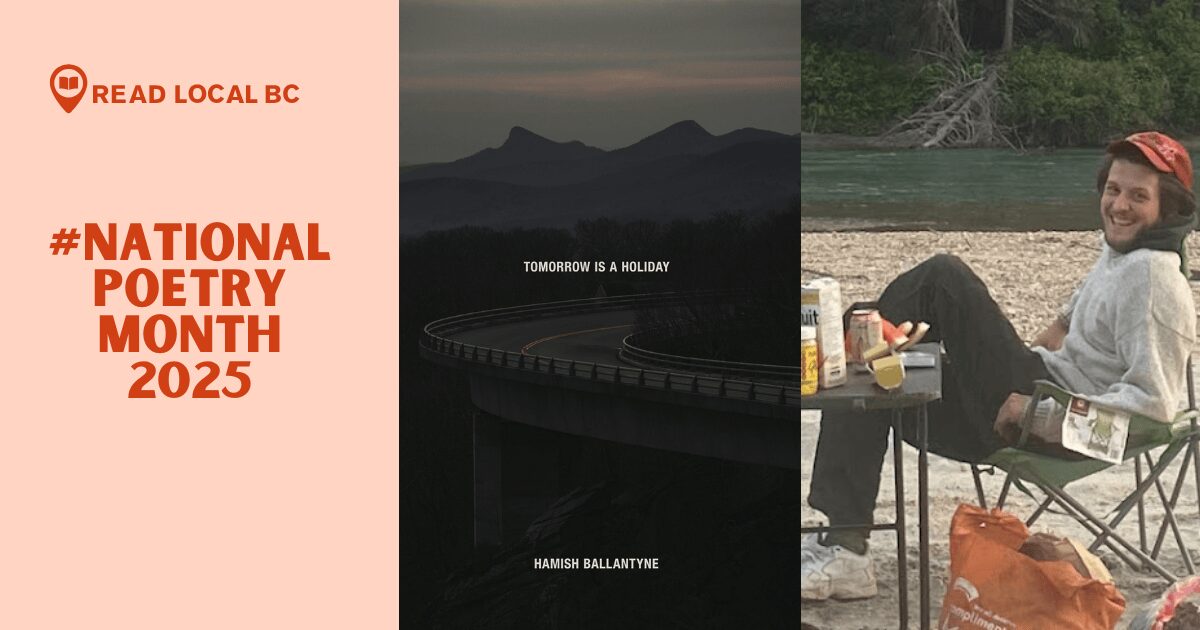

Reprinted with permission from

Tomorrow is a Holiday

(New Star Books, 2024).

Rob Taylor: The promotional copy for Tomorrow is a Holiday describes its poems as “resisting the urge of revelation in favour of idiomatic observation.” Authors rarely write their own copy, so I’m curious about your thoughts on it: in what ways do you see your poems as observing without revealing? Is this something you consciously aimed for while writing these poems, or did you come to see it in the work after the fact?

Hamish Ballantyne: I think a lot about something Daphne Marlatt said, where she contrasts a traditional lyric image—a flying bird from the perspective of a person standing on the bank—to her field of inquiry, which has no reference point; “because the bird’s in flight, you’re in flight. Whoever’s reading.” Maybe similarly I am thinking about speech and writing not as an ideal transmission of intention-meaning-reception but a process of accretion with significant loss, distortion, mishearing, stuttering; a deluded rot that extends right back to the initial thought which is itself not whole. In the end, seeing can’t be primary in the poems because its mediators, speaking and hearing, are activated as sites of breakdown. In this vein, I take a lot of direction from music. I imitate techniques of sampling and covering and draw out the sonic strangeness of each word.

I wrote this book at an early peak of the drug-poisoning epidemic, when a lot of people I knew and loved from my life and also from my work in harm reduction had recently died. Maybe the book is a testament to a resulting fracturing effect.

RT: You’ve translated The Solitudes by seventeenth-century Spanish poet Luis de Góngora. In long con magazine you wrote, of Góngora’s unfinished book, “so little is revealed about the protagonist… that language is the real hero of the tale.”

Here, again, a choice away from revelation to focus attention on the sonic demands of language, and their arrangement on the page (In the opening poem, for instance: “wound knit with white hot / strips of tuna / can”). How did working closely with Góngora’s poetry influence the writing of your own?

HB: Góngora has had a massive influence on me, both in his own writing and via the writing of the many Spanish-language writers he influenced, including Lorca, Machado, Lezama Lima, Juan Rulfo, Cesar Vallejo, Borges. I love the horizontality and ornamentation of baroque writing, its tendency to flood and encompass anything and everything. From Góngora I was most excited with the way he wraps a phrase around his finger and inverts typical sentence structure: a stanza will open as usual with a subject/verb and the object won’t turn up for five lines.

I take a lot of direction from music. I imitate techniques of sampling and covering and draw out the sonic strangeness of each word.

Hamish Ballantyne

RT: In that same essay for long con, you described your approach to translating Góngora as aiming “to reproduce elements of Góngora’s poetic forms (rhyme, metre) in fragmentary, stilted glimpses. I make interpretive leaps of bad faith. I treat Góngora… as a loose cannon whose work constantly escaped his designs for it, and I seek to follow him in this.”

This kind of translation, focused on the energy or “spirit” of the poems rather than the literal meaning or sounds, reminded me of another New Star poet and translator, Roger Farr. In his interview with me a couple years back about his translations of François Villon, Farr said he “was generally more interested in translating things like addressivity, the conspiratorial tone, the pleading for mercy, the warnings, etc. Even where sound and sense are separated, those rhetorical features and the poem’s overall “hum” remain intact.”

Does that resonate with your own approach to translation, maintaining the “hum” of the original, even if most/all else is left behind?

HB: Yes and no. I don’t always honour the spirit of the poems—in fact in some translations I actively work against the original. At a methodological level, my translation process is sometimes so word-for-word as to be highly myopic. I enjoy fertilizing these accidents of misdirection by deliberately pursuing a false cognate or phonic translation, weaving in and out of proximity to the sense of the text.

Similar to Farr, there are central elements of the original poem that are most attractive to me—the mythic register, the anticolonial undercurrent, the wacko sense of time travel (highlighted in Adolfo Bioy Casares’ The Invention of Morel, a 20th century remix of The Solitudes). But I’m mostly interested in translating Spanish Golden Age writing because it is so thoroughly canonized, translated widely and repeatedly over the centuries and subject to enormous academic scrutiny. This creates an interesting back and forth between the work’s historical reception in English and Spanish and the reception of its literary descendants. On top of that, it allows me to be destructive with the original when I want to be. The Spanish Golden Age was a period of intense literary flowering, facilitated by the genocidal expansion of Spain’s empire. The Solitudes is a work with visible commitments and high political stakes—not, as one of its most influential critics called it, “a pure delight in forms.” I think it is important to translate it with more than a plodding obedience to language.

RT: Tomorrow is a Holiday features translations not of Góngora but of his contemporary, San Juan de la Cruz. From amongst the writers of the Spanish Golden Age, what drew you to de la Cruz’s work in particular?

HB: San Juan de la Cruz is a mystic. His writing envisions a semi-sexual physical union with God (which landed him in jail). I am drawn to the ecstatic heart of the work, the possibility of standing outside the self, of escape, the sense of speeding up.

I was also drawn to the poems because of similarities to the form of serial poems I was writing while making this book. Short stanzas, repeating images between sections of his work—for example, in “Fountain,” the element of the original that I worked hardest to maintain is the line that ends every stanza, which temporally locates the poem’s articulation at nighttime. Working toward a sense of meaning as a flickering or stuttering, I tweaked San Juan’s repetition of the image of night and darkness to repeatedly emerge or be encountered in different images.

I love the horizontality and ornamentation of baroque writing, its tendency to flood and encompass anything and everything.

Hamish Ballantyne

RT: Your translations of de la Cruz seem, like your translations of Góngora, very loose—more the “hum” than the content (both Chinese-Canadian cafes and the Halq’eméylem language make appearances in your translation, for instance!). Did you take a similar approach to translating both poets, or did working with de la Cruz require you to change tack a bit, even if subtly?

HB: I had to change tack. San Juan de la Cruz’s poetry is very sparse. Góngora’s is brutally ornate and dense. The San Juan translations also inhabit a recognizably local geography.

RT: Speaking of local geography, you split your working life, seasonally, between picking mushrooms and working in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. How does the labour of each of those distinct “seasons” influence what you write at that time? Are you more productive as a poet during one season or the other?

HB: Summer and mushroom picking is conducive to thinking and writing, whereas the long weekends afforded by shift work in the Downtown Eastside have allowed me to read a lot during the winter, and to rework material from my notebooks.

RT: The second long poem in the book, “Luthier,” opens with an epigraphy from fellow New Star poet George Stanley, who I interviewed for this series a few years back. I see a number of connections between his work and yours, especially in your interest in serial/long poems, in “idiomatic observation,” and in writing on Vancouver. How has Stanley’s poetry influenced your own? Are there other poets whose long or serial poems have been vital to shaping your approach to yours?

HB: I love George Stanley’s writing. George Stanley and the work of other poets who have lived on the West Coast—including Cecily Nicholson, Maxine Gadd, Peter Culley, Clint Burnham, Mercedes Eng, Michael Turner, Jeff Derksen, Rob Manery, facilitated my introduction to and understanding of Vancouver. There’s a romantic turn to George Stanley’s work that I love, a kind of quiet glory, which I think is an extremely difficult tone to finesse. The long poems about Terrace are among my favourite writing I’ve ever read.

In terms of the long/serial poem: Bernadette Mayer, Claudia Lars, Marosa di Giorgio, Alejandra Pizarnik, Aime Cesaire, Lorine Niedecker, Philip Whalen, Michael Cavuto.

Hamish Ballantyne is a poet and translator based on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples (Vancouver, Canada). He works in the Downtown Eastside and as a commercial mushroom picker. Ballantyne has published two chapbooks, Imitation Crab (Knife/Fork/Book, 2020) and Blue Knight (Auric Press, 2022). Tomorrow is a Holiday is his first full length collection.

Rob Taylor’s fifth poetry collection is Weather (Gaspereau Press, 2024). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews on his website.