The following interview is part two of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Here It Will Be Spring

Here it will be spring in February—

here nothing will be as it always was.

Here the barges are not locked in ice,

and the trees do not know my dreams.

The waves come to shore quietly

with rain, the clouds breathe

the ocean over the city, the sickle moon

is hidden down the avenues,

totems sleep on the silver backs

of the river-climbing fish, the lungs fill

with the scents of cedar and fir.

Instead of the wings of cranes,

here the dark boughs rustle for us,

here the fishing nets catch us,

and we push the leaden waves.

Here the salt air covers our bodies,

and swimming to the shallows,

we embrace the world

as with sets of a new kind of fin.

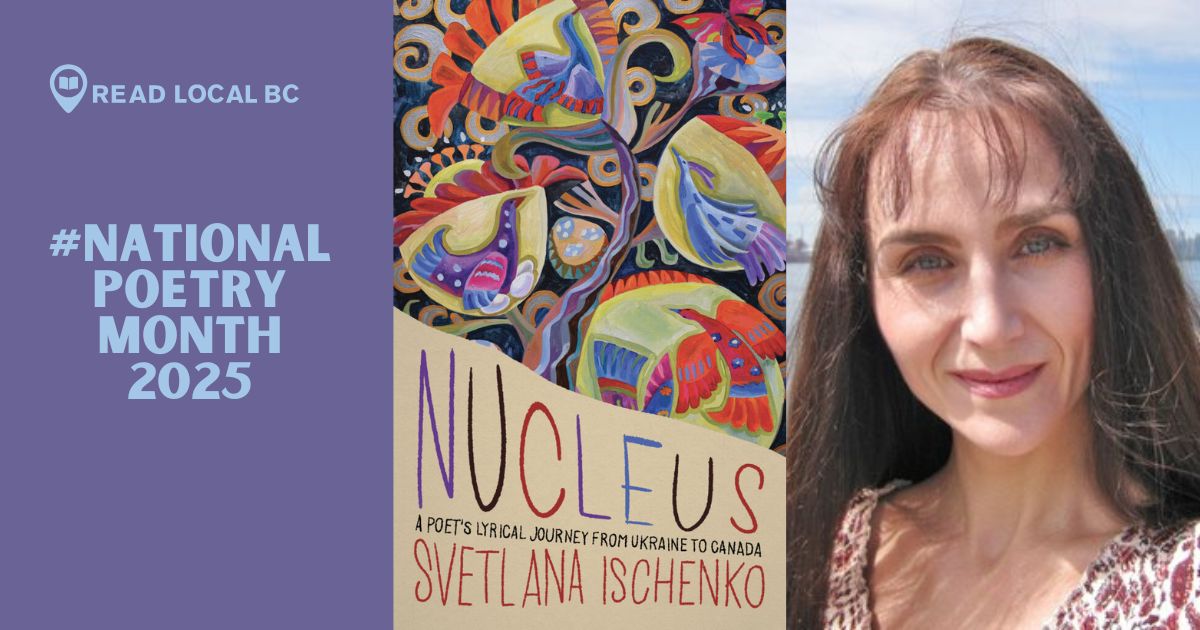

Reprinted with permission from

Nucleus: A Poet’s Lyrical Journey from Ukraine to Canada

(Ronsdale Press, 2024).

Rob Taylor: Nucleus: A Poet’s Lyrical Journey From Ukraine to Canada is your first English-language trade collection, but it comes almost twenty years after your first English-language chapbook, In the Mornings I Find a Crane’s Feathers in My Damp Braids (Leaf Press, 2005). Could you talk about that long gap between English-language publications?

Svetlana Ischenko: It took me that length of time to make a life after coming from Ukraine to Canada. I had to find work to survive as a new immigrant, then had to revamp myself over a period of a few years to find better work. My eldest child was just a small girl then, and I had to take care of her. I didn’t have enough free time to develop English-language skills to the level where I could produce a full-length manuscript in English. Later I gave birth to two more children and, of course, they along with my various jobs took over my life. I had little time to work on writing poems in English, though I continued to write in Ukrainian. I knew I couldn’t rush towards English publication even if I wanted to! So, for several years, as time permitted, most of the writing I did in English was translations of the well-known Ukrainian poet Dmytro Kremin into English (I also translated several English-language Canadian poets into Ukrainian for a couple of Ukrainian magazines). I published work I produced in Ukrainian in Ukraine. I think my translation work between Ukrainian and English was a lucky thing. It helped me become a lot more fluent in English. In any case, yes, it took me quite a while to get to where I had a manuscript of my poetry in English.

RT: Nucleus celebrates both Ukrainian and Canadian cultures, your homeland and your “new” home (“new” in quotation marks, as you’ve been here for 23 years!). Did you feel an increased sense of urgency to publish a first English-language collection following Russia’s war on Ukraine? To celebrate Ukrainian lives and culture at a time when they are imperiled?

SI: I prepared Nucleus and sent it out to a couple of publishers in 2020-2021, a little before the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. One of the poems (“Amazons of the Steppes”) reflects in a specific way the events of 2014 when Russia invaded and annexed parts of Ukraine in the south and east. Much of the rest of the book is my attempt to evoke Ukrainian culture and identity alongside an exploration of what it has meant to me to be a Ukrainian-Canadian. I think I’ve felt a need to celebrate Ukrainian culture as a component in a book of my poetry in English ever since I arrived in Canada, but this intensified around 2014. It became even more important to me in 2022.

When Wendy Atkinson accepted my manuscript for Ronsdale Press in 2023, the full Russian invasion of Ukraine was in its second year. My friends and family in Ukraine were suffering the consequences of the invasion, seeing their homes destroyed and losing loved ones. It was beyond a nightmare. My mother was living alone in Mykolaiv (my hometown in the south of Ukraine) in an old apartment building with shelling often going on all around her. Luckily, a friend of mine brought her drinking water and groceries once a week. When I heard from Ronsdale Press that my book would be published, it lifted not only my spirits but also my mother’s and the people I am close to in Ukraine. It meant that more people in Canada might come to know about Ukraine and its culture and traditions, through a Ukrainian-Canadian’s eyes. Though the poems in Nucleus aren’t about the war in Ukraine, the invasion and the threat to the life of the country made me feel that the publication of the book was a kind of justification.

To say a few words about these poets and their deaths is to say almost nothing because each of them contained in themselves a universe of knowledge, history, art, poetry, and circles of friends and families, and readers across Ukraine.

Svetlana Ischenko

RT: Can we talk a little more about “Amazons of the Steppes”? In it you describe Ukrainian women fighting the Russian invasion as “present-day Amazons.” I can only imagine how difficult it must be to watch the war unfold, particularly when the battle for Mykolaiv was fought in the days following the invasion.

In an interview, you mentioned that two Mykolaiv poets you knew had already died in the conflict, and that many other friends and colleagues are struggling to keep Ukrainian arts and literature alive under very difficult circumstances. Could you speak more about your experience of the war, watching and writing from a distance?

SI: Both the poets who died were members of the Mykolaiv branch of the National Writer’s Union of Ukraine (an organization I still belong to). Their names were Nadia Agafonova and Hlib Babich. Nadia, a young poet and visual artist, was killed on March 29, 2022, during a Russian missile strike at her workplace, the Mykolaiv Regional State Administration’s headquarters. Hlib Babich, a military officer, a poet and a songwriter in a well-known group called Kozak System, was killed on July 29, 2022, by a Russian anti-tank mine in the battle for the city of Izium in the Kharkiv region of Ukraine. Hlib’s poetry is truly incredible. To say a few words about these poets and their deaths is to say almost nothing because each of them contained in themselves a universe of knowledge, history, art, poetry, and circles of friends and families, and readers across Ukraine.

Yes, I watch this war from a distance, and therefore I can’t write about the ongoing experience first-hand. Only writers who have been living through the war from the beginning can do that. But I can write of what I witnessed and felt when I travelled to Ukraine in January of 2024, going from Vancouver through London and Krakow to the Polish border along western Ukraine, and then going by bus across southern Ukraine to Mykolaiv. My mother was quite ill. I was hoping to see her before she died. Unfortunately, she passed away while I was in Poland buying a bus ticket from Krakow to Mykolaiv, so I missed seeing her by one day. The entire way across Ukraine was, of course, a war zone. Everywhere we passed through, I saw bombed-out towns and fields. There were constant air raid sirens and frequent shelling.

I stayed in Mykolaiv for three days, arranging for my mother’s burial, and headed back to Vancouver. I saw what had happened and was happening to Mykolaiv during the continuing series of military assaults.

I wrote several poems about my brief time in Ukraine. I’ve included them at the beginning of my next English-language manuscript. These pieces are about what I’ve seen of the war, and I’ve allowed myself to write them because they are based on my direct experience. But, again, my next book won’t be about the war per se, but about meaning in life, everyday human experiences, and places we are deeply connected to and to which we belong.

I think my translation work between Ukrainian and English was a lucky thing. It helped me become a lot more fluent in English.

Svetlana Ischenko

RT: I’m so sorry for your loss, Svetlana. Why do you think, in the midst of all this pain and destruction, that it’s important to protect the arts, perhaps poetry in particular?

SI: I’d like to say that poetry writing and reciting along with songwriting and song performing have increased dramatically in Ukraine during the war, especially through social media, at public libraries, and in metro stations. People need their feelings and experiences expressed not only through the relaying of bare facts but also through imaginative communication. I think people instinctively go to poetic language as appropriate for recording their most intense experiences. Maybe only poetic language can truly register the heinousness of what comes with war. At the same time, maybe sharing stories and experiences through the sounds and rhythms of poetry unites people in possible healing. For me, to save and protect poetry is to save the history of one person as well as of a whole nation. It’s a concentration and preservation of a period and the character of a nation within the music of a language. So, in a time of war, poetry and the other arts become more essential than ever.

My friend and ex-colleague Iryna Tubaltseva, a stage actress in the Mykolaiv National Ukrainian Theatre, sent me a video last February in which she recites “Contra Spem Spero,” a poem by the classic Ukrainian poet Lesia Ukrainka. She recites the poem on her apartment balcony in Mykolaiv, and in the night sky and city lights in the background, you can hear and see (in real time!) air raid sirens and explosions. This poetry video is a vital time capsule containing the human spirit.

RT: Дерева злетіли парами (The Trees Have Flown Up In Couples), your 2019 Ukrainian-language collection, won that year’s Mykolaiv Book of the Year in Ukraine. As someone who publishes in two languages and two countries, what is your sense of how your poems are received differently in each? Does the nature of the poems change in translation? Or, perhaps, do the language and culture of the reader transform the poems?

SI: It seems to me that my poetry is received in similar ways in both countries, at least context-wise and emotion-wise. I tend to write on a personal level about enduring themes, and, hopefully, that comes through even in the poems I write in English. Of course, I’m still more deeply attached to the Ukrainian language than to English, so my poems in Ukrainian are more accomplished in terms of sound, and Ukrainian listeners can appreciate certain aspects of the poems like rhymes, especially in the poems I’ve written in classical forms. I have several poems I’ve written in Ukrainian that I’ll never try to translate into English. I know that too much of the cultural context, the references, and the sounds of the language will get lost.

When I translate a poem, my own or another’s, I try not only to be accurate in bringing forth the word-for-word meaning and rhythm of the original but also try to incorporate where necessary an explanation of a cultural word or reference. It’s a kind of accommodating of the reader. In this process, the poem in translation acquires some extra communication. Hopefully, the poem’s nature stays true to the reader! In any translation work, I try to preserve the “voice” of the original author as much as I can. It’s a wonderful challenge.

RT: You mention in the introduction to Nucleus that the final section of the book features your first poems written in English (as opposed to being written in Ukrainian and later translated), and that, funnily, these might “be amongst my most Ukrainian poems.” Could you expand on that a little? Why do you feel that’s so? Did writing in English naturally make you think of a Canadian reader first, who might not be familiar with the Ukrainian references in your other poems? Did you find yourself writing as an “outsider” of sorts, explaining yourself to the centre of the culture?

SI: With my poems that I’ve written directly in English as a first step, I’ve known as I was writing them that I wanted to speak about Ukrainian matters even though I was writing in the language of a Canadian audience. Yes, this meant that I had to explain aspects of Ukrainian culture and history in those poems. I felt both outside and inside Canadian culture. What was interesting for me was finding that writing from the perspective of an immigrant in Canada, I was illuminating for myself elements of my Ukrainian experience and identity. It was like returning through myself, through the Canadian I have become, through to the Ukrainian I still am. Beyond all that, of course, I found that an individual’s core identity owes nothing to any nation.

Maybe only poetic language can truly register the heinousness of what comes with war… For me, to save and protect poetry is to save the history of one person as well as of a whole nation.

Svetlana Ischenko

RT: Sonnet crowns, sequences of sonnets in which the last line of one sonnet becomes the first line of the next, are appearing with increasing frequency in poetry collections by BC poets (I’m thinking, recently, of Barbara’s Nickel’s “Corona” sequence in Essential Tremor, or Bradley Peters’ multiple crowns in Sonnets from a Cell). But you’ve gone and outdone them all in the opening sequence in Nucleus, “A Banner of Cloth.” A fifteen-poem sequence, “A Banner of Cloth” is a heroic crown, in which in addition to the other requirements, the final poem in the sequence is built out of the repeated lines in the preceding fourteen poems. It has a stunning effect, like a magic trick, or the moment when the intricate gears of a music box all click into place. Could you talk a little about taking on that form? What did you find were its challenges? Assuming it was initially written in Ukrainian, did you encounter particular challenges in bringing it into English?

SI: I love writing within a form, especially a classical form. It’s a great challenge and there’s a satisfaction in it for me if I think I’ve succeeded. In Ukrainian, I’ve written three heroic crowns of sonnets and many Petrarchan sonnets. It’s a fun challenge!

The challenge for me in writing a heroic crown of sonnets is mostly in first writing the key sonnet (though in a final product, it will be the very last poem). The key sonnet has to be the source of the themes, statements, and antitheses for the other fourteen sonnets. After that, the challenge is coming up with not less than twenty rhymes for the words at the ends of each line of the key sonnet. Then I go ahead within that organization. It seems like math, and it is, in some senses.

I wrote “A Banner of Cloth” in Ukrainian not long after I came to Canada, then translated it into English. I didn’t even think about trying to translate my Ukrainian-language rhymes into English. It would have been impossible. But I kept to the heroic crown structure and tried to stay true to the sense of each thought. Several times, I had to add small amounts of the sort of “extra communication” I’ve mentioned to explain Ukrainian words and/or references. Also, I inserted notes to this sonnet sequence at the end of Nucleus.

RT: The second section of Nucleus, entitled “The Colours of Love,” contains within it the titles for both your aforementioned 2005 English-language chapbook and your 2019 Ukrainian-language full-length book. The poems in that section, many of which are untitled and flow together in their reading, have clearly been with you for a long time and have had many lives! Could you talk about the importance of the poems in that section to you, and why you chose to centre them in the titles you chose for both Canadian and Ukrainian audiences?

SI: It’s interesting that you notice this about the second section! These are the poems in Nucleus that represent the time when I was going through the process of trying to translate poems into English that I’d written in Canada but in my native language. I had varying levels of success! After a while, as I got better at English, I forgot about trying to translate accurately and just tried to rewrite the poems in English, my new language. Again, I had varying levels of success. Around this time, I was also trying to simply write poems in English. Some of the poems in the second section of Nucleus have longish lives because they’re the poems with which I was going through my process. These poems are important to me as markers of the transition I was making from writing solely in Ukrainian to writing in English with at least a small amount of confidence.

RT: “The Colours of Love” closes with the poem “The Colours of Chagall’s Love,” from which you derive the section’s name. Could you tell us a bit more about that poem?

SI: I’ve painted since childhood. My media and styles have changed every decade of my life (from watercolour to gauche, to oil, to acrylic) but I have never stopped loving applying paint to paper or canvas. I love the body of works by Marc Chagall. Chagall stayed true to his child’s vision of the world, especially the multiple colours of the circus where images burst into hues of imagination and love, turn and swing, and float one on top of another, revealing and hiding subjects and objects, like transparent metaphors on top of metaphors. Through all the turbulent years of revolutions, pogroms, and persecutions of Jews in Eastern Europe, Chagall saved in his paintings the innocent soul of a child, the sense of eternal love in colours. That’s why this poem is important to me. I wrote it in the first months after I immigrated to Canada, and originally, I titled it in Ukrainian “Dreams in the Time of Gravitation” but then, translating it, I came up with a different title in English that I thought better suited the poem. Chagall was an immigrant in France, but he never lost his identity, his cultural roots, and his centredness where everything gravitated towards the humanity and love that permeates all his paintings. I see his paintings as poetic representations of an artist through the colours of love.

I found that an individual’s core identity owes nothing to any nation.

Svetlana Ischenko

RT: Cranes and their BC equivalent, great blue herons, both have poems dedicated to them in Nucleus. What importance does each have on your thinking about your two homes?

SI: I have to tell you about two events in my life. I’ve been fascinated with birds since my childhood. The first time I saw cranes flying in V-formation very low in the sky above me was in the Mykolaiv region at the beginning of September of grade seven. I was sent with the other students not to the classrooms to study but to the fields of the collective farms in the old Soviet Union to gather the harvests of potatoes, tomatoes, beets, carrots, and onions. While we were packing the onions into nets, I cut my finger on a harvest knife. At that moment, I heard a distinct, unusual sound overhead. The cranes were calling as they flew, and everyone in the field lifted their eyes to see these astonishing birds winging together in their V-formation. I was in awe and forgot about my bloody finger! But I’ve never forgotten the moment. It was like I was being thrown back to the beginning of time, and farther, to eternity.

The second event occurred when I touched a wild crane for the first time! It was here, in Vancouver, when I visited a bird sanctuary on an island at the mouth of the Fraser River. To my delight, two cranes were present in the area and were flying from one marsh to another, close to the water’s edge. I stretched out my arm and opened the palm of my hand full of seeds for them, and one of the cranes simply stepped toward me and ate the seeds from my palm. I was in the same state of awe again! When a wild, majestic bird like this one touches your palm it’s a heart-stopping moment: it’s wild, ancient, warm, soft, and beautiful.

In Ukrainian culture, cranes represent freedom and love. They represent the sadness of the dying away of vegetation in the natural world in autumn and the anticipation and joy of rebirth when they come back to their grounds in the spring. In Ukrainian folklore, they fly the souls of the dead to paradise. They also symbolize the longing of expatriates for their native land.

To my surprise, I found out that the symbolism of the Great Blue Heron in First Nations culture in Canada is almost the same: the heron represents steadfastness, self-reliance, rebirth, renewal, calmness, along with silence, reflection, harmony, and wisdom, all connecting us to the larger circle of life and death. This bird, as ancient as Earth itself, elegant and graceful, does remind me of the Ukrainian crane! And, yes, the symbolic meanings of these two birds connect me to my two homes, Ukraine and Canada.

RT: You spoke at the beginning of our interview about translating the poems of Dmytro Kremin, a poet to whom you dedicate a poem in Nucleus. How did Kremin’s work and life influence your own?

SI: Dmytro Kremin (1953-2019) had a huge influence on me and was a whole chapter in my life. He is still an inspiration to me. When I was in my late teens, I brought some of my poems to him at his office at the local Mykolaiv newspaper, where he was the head of the Literature and Culture department, and he took the poems for publication. I was a young stage actress at the Mykolaiv National Ukrainian Theatre at that time, and Dmytro Kremin was a well-known Ukrainian poet whose body of work was studied in schools and universities. His poems were often recited on the radio and were used as the lyrics in many popular songs.

Kremin became not only my mentor but my lifelong friend. He was brilliant, welcoming, kind, down-to-earth, and charismatic Renaissance man: a poet, essayist, translator, journalist, university professor, teacher, theatre critic, and visual artist. He felt a responsibility to educate and protect young Ukrainian writers in the face of the Russification of Ukrainian culture and literature. I feel fortunate, remembering the many poetry readings I did with Dmytro in Ukraine at libraries, colleges, and universities.

Kremin passed away in 2019 and I wrote the elegy you mentioned (“Dmytro Kremin: A Portrait”). On the day of his funeral, crowds of people in Mykolaiv came to pay respect to a man who is considered a great Ukrainian poet of our times. Two years before he died, when I visited Ukraine in 2017, I was able to present Dmytro with a dear-to-his-heart gift from Canada: copies of the Canadian-published book Poems From the Scythian Wild Field: A Selection of the Poetry of Dmytro Kremin (Ekstasis Editions, 2016). The book is a selection of Kremin’s poems I translated into English with help from Russell Thornton. It was the first English translation of Kremin’s work in book form. Kremin’s poetry is now appearing in English translation in other collections, most recently in the U.S. His work has also been appearing in translation in languages as diverse as Slovak and Mandarin.

A Ukrainian launch of Poems From the Scythian Wild Field took place in 2017 in Mykolaiv at a library where Dmytro Kremin and I had done a poetry reading together more than twenty years before; Dmytro recited his original poems in Ukrainian, and I recited them in English. It was a wonderful occasion.

I keep in touch with Kremin’s wife Olga and his son Taras. Taras Kremin is a Ukrainian politician (Commissioner for the Protection of the State Language) and a poet. He continues his father’s work, supporting Ukrainian writers, artists, actors, and scientists, and promoting the Ukrainian language.

RT: Do you have other Ukrainian poets you would recommend curious Canadian readers look into?

SI: First and most of all, I’d say: Lina Kostenko. Of all Ukrainian poets—even going back to the classic poets Taras Shevchenko, Lesya Ukrainka, and Ivan Franko—Kostenko is my favourite. She’s in her mid-nineties now and is the living matriarch of modern Ukrainian poetry. Of the poets of the Ukrainian dissident movement of the late twentieth century, there are Vasyl Stus, Mykola Vingranovsky, and Vasyl Symonenko. More recently, there’s the first recipient of the Dmytro Kremin Poetry Prize, Ihor Pavliuk. My other favourite contemporary Ukrainian poets are Oksana Zabuzhko, Serhiy Zhadan, Hlib Babich, and Teodozia Zarivna.

Svetlana Ischenko is an award-winning poet, translator, actress and teacher. She was born in Mykolaiv, Ukraine, where she established herself as a stage actress and poet before immigrating to Canada in 2001. She is the author of several books of poetry, essays and dramatic plays in Ukrainian and English. In Canada, her poems have been published in The Antigonish Review and Event and were included in the anthology Che Wach Choe/Let the Delirium Begin (Leaf Press) and the chapbook In the Mornings I Find a Crane’s Feathers in my Damp Braids (Leaf Press). Her first English-language poetry collection is Nucleus: A Poet’s Lyrical Journey from Ukraine to Canada (Ronsdale Press, 2024). She lives with her family in North Vancouver, B.C.

Rob Taylor’s fifth poetry collection is Weather (Gaspereau Press, 2024). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.