This post was compiled by Rob Taylor.

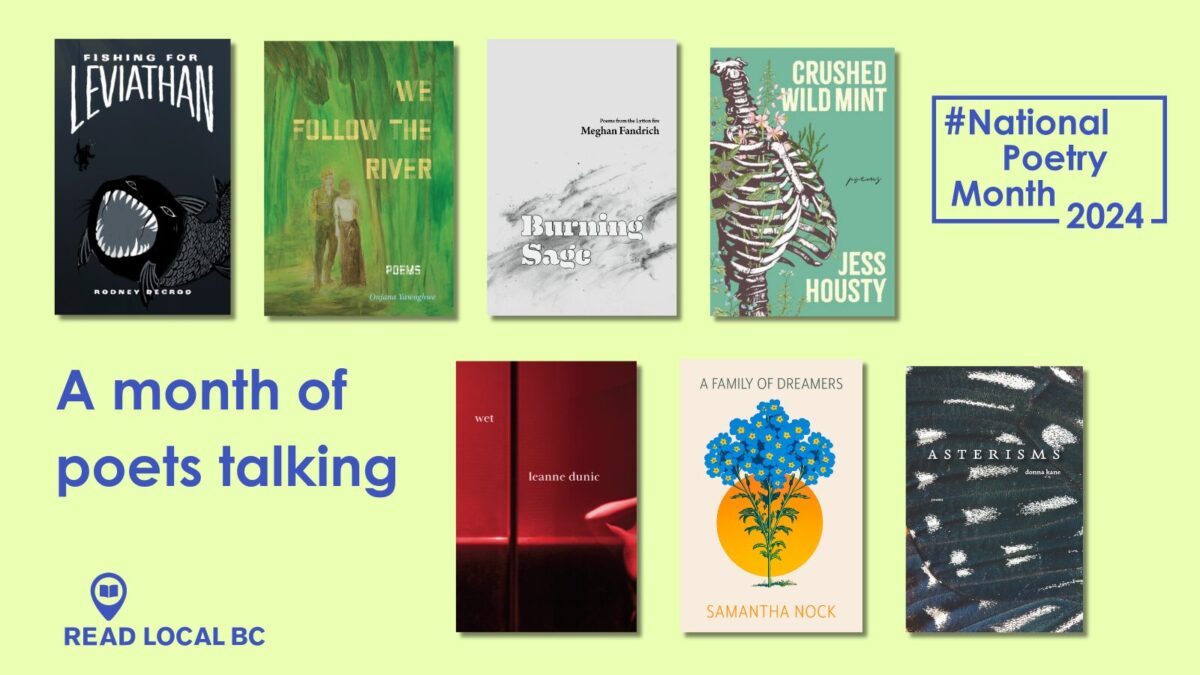

Throughout this series, we’ve spoken with BC poets about their new books. Now they get a chance to share some love with others! We asked each featured writer to write about a BC poet who influenced or inspired them.

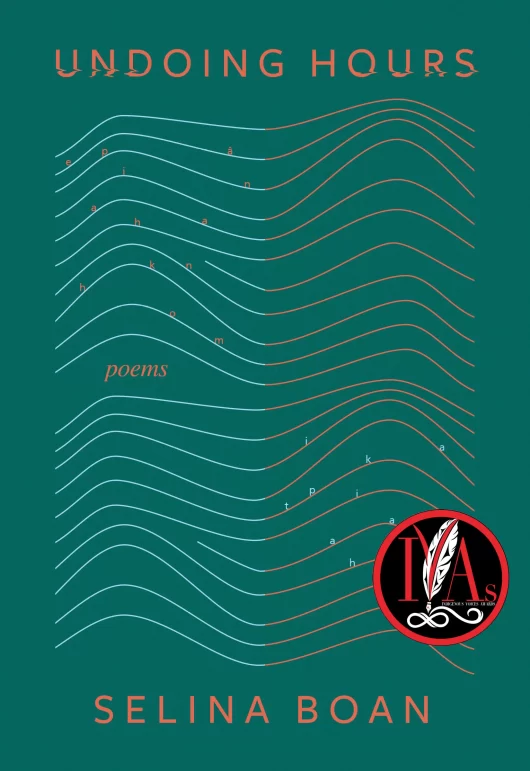

Samantha Nock on Selina Boan

Selina Boan’s Undoing Hours is a work I find myself returning to again and again. I remember meeting Selina, and seeing her perform, and absolutely just falling in love. Selina writes in a beautiful and honest way that brings you fully into her words and feelings. It’s like sitting down and listening to an old friend talk. The way she connects the process of being a Cree language learner with other parts of her life is something I haven’t seen before and find deeply inspiring.

One line I think of often, from Boan’s poem “all you can is the best you can,” is “what i’m trying to say / is english is failing me.” The line lands near the end of a long poem that is processing a very personal and emotional moment in the poet’s life. I’m not sure what her intention is in this line, but it makes me think of being a Cree language learner. You know you have this whole world that is your inheritance and learning your language is like having puzzle pieces fall into place. But with this you also learn how limited English can be—all you want to do is reach into some part of your brain or ancestral memories and pull the Cree out. Undoing Hours is such a deeply vulnerable, honest, and special work that I feel everyone needs to read, even just to witness. I cannot wait to see what Selina writes next. Her words are a gift to us all.

You can read Samantha Nock’s interview from this year’s series here.

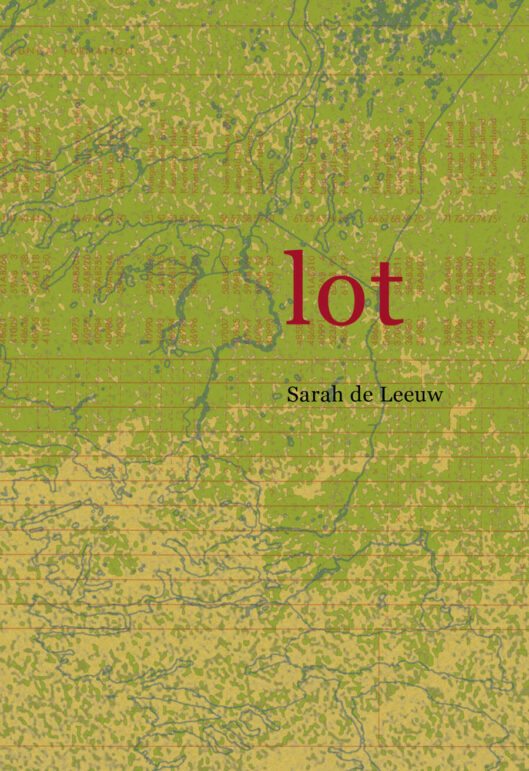

Leanne Dunic on Sarah de Leeuw

Would any of my books exist if it wasn’t for the essays and poems of Sarah de Leeuw? Her book Geographies of a Lover serendipitously found me as a new writer and I still think about it regularly. The work demonstrated how one can unabashedly harness language and content. The book is cinematic and impassioned, explicit and refreshing. Upon first reading, I was hooked. Geographies of a Lover revealed the cartographic possibilities of narrative. Now I could see what a book-length poem could do.

I wanted to channel Sarah’s eloquent wildness in my own writing. From her, I learned I could allow landscape to be as important to the narrative as any character. In Geographies, she anchors poems with coordinates (i.e. “46° 46’50.09″N, 71° 10’58.43″W”)—titles that offer names to places that are simultaneously specific and obscure. Mapping and landscapes are themes throughout her books. These themes continue in her most recent book, Lot, which is another gem that I urge people to read. The book is complex, weaving connections between landscapes and histories and people, through brilliantly executed distillations and constellations. The gorgeous cover is a bonus.

Her profound influence on my work led me to invite her to edit Wet. It’s among one of my greatest fortunes that she agreed! She pushed me to find my own ways for erotic expression and helped me take the work to the next level.

Sarah is one of the most skilled writers I know. Mapping is her method. Land is her language. Her oeuvre demonstrates her endless curiosity and care. Not only does she write memorable poetry, but she also is the Canada Research Chair in Humanities and Health Inequities and is involved in countless initiatives helping better our communities. Her multifaceted body of work has also inspired me as a PhD candidate/general human. She’s a powerhouse!

You can read Leanne Dunic’s interview from this year’s series here.

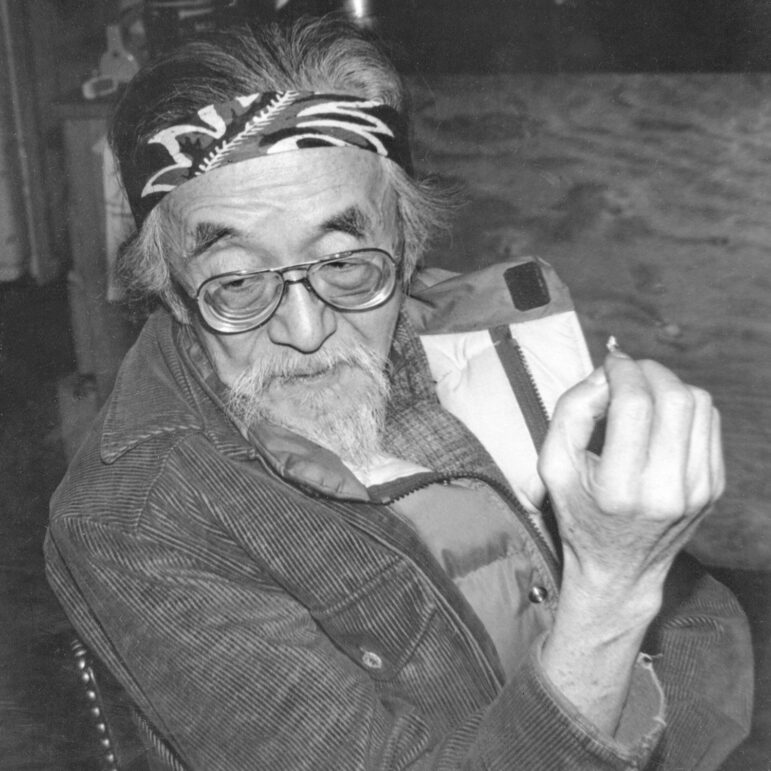

Onjana Yawnghwe on Roy Kiyooka

Roy Kiyooka is the coolest. Not only was he an incredible visual artist, creating abstract paintings (his modernist paintings with their hard edges and bright colours are absolutely beautiful), he was an interdisciplinary artist who created works in film and photography. He was a great poet, with such a sense of joy, and simplicity in expression. He was Japanese-Canadian and grew up during World War II, and so he had to figure out who he was within this country that put his people in internment camps and he had to figure out what his relationship with English was (he wrote in “inglish” instead of “English” for example).

He had amazing ideas that were simple but so brilliant, like this chapbook StoneD Gloves, where he took photographs of abandoned gloves and wrote poems to accompany them. I loved the lyric beauty and heart of The Pear Tree Pomes. Instead of pursuing trade publishing, he created his own chapbooks, and combined his visual art background with the poems with things like photography or collage. He was a complete inspiration to me; so many of my projects were directly influenced by him, and the little micropress that I had with a couple of friends, fish magic press, took on that hand-made poetic aesthetic (I even created some of my chapbooks in a limited edition of 36, just like he did). He reminds me of William Blake in a way, combining art with writing, going his own way, making his own books; a true independent spirit. Kiyooka just opens up space and possibility in writing and art. I highly recommend the book of his collected poems called Pacific Windows edited by Roy Miki.

You can read Onjana Yawnghwe’s interview from this year’s series here.

Meghan Fandrich on Susan Musgrave

I know that poetry is meant to be savoured. Take a single poem; read it slowly, carefully. Feel each word on your tongue. Taste every image. Let the complexity of flavour build, line by line, until the twist of ending, sudden zest of lemon, surprises you with its sharp clarity. Close the book, slowly, carefully, and think about it.

But that’s not how I read Exculpatory Lilies by Susan Musgrave. I couldn’t just take one poem at a time. I couldn’t close the book. I couldn’t put it down.

There’s something about Musgrave’s poetry. She invites you to sit down at the water beside her. Her voice—you can hear it so clearly—tells you about her life, her love, her grief, and your tears well up as you listen to her. And you laugh with her. And when you look up at the stormy grey water, you see the faces of the people she’s been telling you about.

And you don’t feel as though you’ve been reading at all; you haven’t been taking dainty bites of any heavily seasoned dish. You’ve been sitting beside her, listening, living. Savouring. Being inspired.

You can read Meghan Fandrich’s interview from this year’s series here.

Jess Housty on Samantha Nock

I feel a real debt of gratitude to Samantha Nock for bringing her debut poetry collection, A Family of Dreamers, into the world. Her poems are so authentic and sensory and give a visible form to so many of the ideas and experiences that shape us as Indigenous people seeking an identity in a complicated world: families and lovers, body politics, heartbreak and liberation, sharpening senses of self. And I’m also perpetually in awe of Selina Boan and Undoing Hours – that collection is an ode to decolonial dreaming and the power of language. When I launched Crushed Wild Mint, it felt wrong to stand alone with my book and hold it up to an audience. I can write because others write and have written, and extending myself into the world with poems in my outstretched hands only feels safe and possible because, like sheaths of sedge, together we’re a meadow and we hold each other up.

I’ll always be grateful to Samantha and Selina for saying yes to standing with me at my Vancouver launch, and to bringing their grace and brilliance and big auntie laughs into the room with me and my words. I have the privilege of flourishing in the homelands they write into existence, the expansive identities they make real and possible, the sense of kinship and community they imagine into being. In a world and society and moment in time that still often oppresses Indigenous peoples, Samantha and Selina’s poetry is liberatory.

You can read Jess Housty’s interview from this year’s series here.

Rodney DeCroo on Russell Thornton

Russell and I are very different poets, but we have a few things in common. We write out of lived experience. It’s something I need from the poetry I read. I write poetry out of an urgent need to make some sense of the turmoil inside and outside of me. And it’s not just about pain. It’s also about giving voice to experiences that show me glimpses of beauty, even transcendence, in ways that aren’t simply about me. I’m not saying I succeed at that very often, but Russell does. Like many people I have struggled a lot and poetry has elevated those struggles and helped me to understand that’s what being human is about. We’re not alone. I have felt closer to poets I have never met while reading one of their poems than people I have known for years. I have found tremendous solace in Russell’s poetry. I have read most of his books several times and I often go back to them for certain poems. Those poems are a part of me like certain songs, novels, films and memories are.

His most recent book, Answer to Blue, sits on my desk next to my computer. Nearly every day I read a few poems from it. Usually while I drink my morning coffee. Russell has written a lot of fine poems. He has written a few that are as good as poetry gets in my opinion. Not many poets can say that. I can’t. It’s an unforgiving business, trying to write even a decent poem, but Russell makes it look effortless. That’s the trick the best poets pull off. As Yeats wrote, “‘A line will take us hours maybe; / Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought, / Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.”

You can read Rodney DeCroo’s interview from this year’s series here.

Donna Kane on Jan Zwicky

I am quite sure I have read every book Jan Zwicky has written. Whether it’s a philosophy text or poetry, there is an integrity to her work that feels intensely pleasurable and true, her ideas so clear, so fiercely intelligent, and also compassionate. When I was working on the poems in Orrery, I reached a point where I no longer felt they were working, and thought, what are these poems even trying to do? Then Jan’s The Experience of Meaning arrived in the mail. I had people coming and going all that weekend (my husband runs an eco-tourism business and our ranch is often a stopping place for guests heading up or back down the highway), so I escaped to a nearby slough on a warm summer afternoon and sat with the wind sifting through the tall grasses, listened to birdsong, and read Jan’s theories of the gestalt, where meaning arises from the apprehension of the material world but still has its genesis in it. With so many of us feeling over-teched and disconnected from nature, the idea of gestalts never felt more necessary. I realized I’d been losing my appreciation for and experience of gestalts. In The Experience of Meaning, Jan included an image of a Necker cube, and for a long time, the illustration sat inert on the page. It panicked me. Jan’s book not only reinforced in me the essentialness of meaning, but the importance of experiencing it, and I continued to keep that in mind while writing the poems in Asterisms. And even though science has entered my writing in ever-increasing ways, my aim is not to dissect the world into discrete, aggregate parts, but to better understand the meaning and value of the whole. Also, thankfully, the optical illusion of the Necker cube now shifts back and forth at will.

You can read Donna Kane’s interview from this year’s series here.