The following interview is part seven of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

A singer from Tainan takes the stage. She wears a polka-dot dress.

Between songs she banters about the haze affecting her voice. She says,

Birthdays are not a celebration.

She tilts her bobbed head, wonders aloud why she was born, why she will

die. Is it her birthday today?

She and I both know we are flotsam.

I chew the straw in my drink. With my mind’s eye, I send her an image: an

oceanic cave, tepid water. An invitation.

Blood pounding, I approach and tell her I love her voice. She asks my

favourite singer. I show her photos on my phone of Neil Finn.

Ah, Crowded House.

We grin and laugh. I’m surprised she knows of him.

I’ve used the extent of my Mandarin. Our conversation ends and I return to

my stool.

Reprinted with permission from Wet (Talonbooks, 2024)

Rob Taylor: Wet is a work of poetic fiction inspired by your experience living and modeling in Singapore. In it you describe Singapore as a city of great wealth, but one which often feels highly unnatural: poisoning animals (lizards, birds) and mistreating foreign workers, with shops full of “H-TWO-O isotonic drink” and NEWater (made from recycled urine) which people drink instead of water.

Compounding this, when you were living there Singapore was caught in the midst of a months-long drought and corresponding forest fires, often making the air unbreathable. Midway though Wet you write, “The truth: I think I’m a monster.” To what extent is that “monstrous” feeling connected to your, or your speaker’s, feeling of disconnection with the natural world?

Leanne Dunic: When I was a model in Singapore nearly two decades ago, I was simultaneously the owner of clothing boutiques. Experiencing the real and usually unglamorous side of modelling, I realised how I played a role in the seemingly never-ending patterns of consumption. A few months after I returned from my modelling stint, I decided to sell the business. Of course for all of us, it’s a precarious balance between taking care of self while also considering the ripple effect on other earthkin. I try to do what I can, and I hope this book will help others think of their place in their environments/communities.

RT: As an “American-born Chinese girl” modelling in Singapore, your speaker seems positioned as an outsider everywhere: Chinese in some people’s eyes, American in others’. You, too, move between countries and cultures frequently, and your books often mix prose, poetry, visual art, and music. You not only write in hybrid forms, but you teach them at SFU.

Do you see a parallel between your hybrid life and your hybrid art? Do you think your border-crossing life inspired your genre-crossing art?

LD: Absolutely, I think my mixed-race identity and transnational tendencies have influenced how I create. For my PhD research, I’m exploring the possibilities of something I’m calling “amphibious poetics”—my artistic practice, like an amphibian, moves fluidly between environments and is multiple in genre, form, content, aesthetic, and ecology. This approach allows me to let the content dictate how it wants to manifest as far as form is concerned.

It’s a precarious balance between taking care of self while also considering the ripple effect on other earthkin.

RT: Does your amphibious nature inspire your interest in short blocks of text, which straddle the worlds of “prose poem” and “flash fiction”? What does writing between genres allow you to explore that might be foreclosed to you if you wrote a more traditional book of fiction or poetry?

LD: This is exactly what I’m interrogating with my PhD work. Check back in a few years.

RT: Interesting! Can you tell us a little more—a sneak preview of sorts?

LD: The PhD is a practice-as-research program through RMIT (Australia), but the campus is in Ho Chi Minh City and most of it happens remotely. It’s in creative writing, but much of my research is based on my photographic practice. It’s a great program for me!

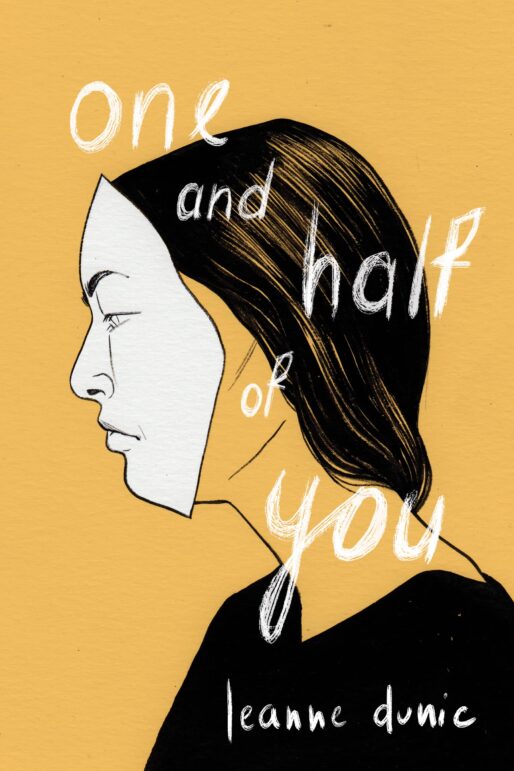

RT: That sounds fascinating. I loved how you blended together poetry and photography in Wet. Another genre-blending aspect of Wet is your choice to write a fictional account that often hews closely to your own experience. Your last book, One and Half of You was a poetic memoir, but you made a different choice here. Why was that important for this story? What did ranging more widely from your personal experience allow you to access?

LD: Yes, I needed fiction in order to create a narrative arc. Also, it’s fun to make stuff up to enhance the message and themes. I think it’s a much more interesting book with the characters and their relationships I’ve created.

RT: For me Wet is in part a book about deprivation and desire—social, sexual, environmental—and how deprivation strips away facades, revealing the true nature of the individual (or city, or global economy) hidden underneath. One of the first photos in the book shows the statue of a playful woman in a dress. One hundred pages later, we come to a photo of a near-identical statue, but this time naked.

LD: The first statue is actually of a snail-woman. The dark part is the shell door plate that gets closed during hot, dry weather—I know it’s hard to tell from that angle. The statue at the end is intended to be a contrast to the statue at the beginning, no longer needing a shell door for protection from the elements (metaphorically and literally).

RT: Did you, similarly, get to a place where you no longer need a shell door in Singapore? If so, was this connected in any way to your choice to sell your clothing company?

LD: I think, rather than abandoning, I metamorphosed, as I continue to do. Yes, selling the store was a big part of it. I then decided to pursue writing and other creative works seriously.

My artistic practice, like an amphibian, moves fluidly between environments and is multiple in genre, form, content, aesthetic, and ecology.

RT: I’m grateful you metamorphosed, then!

Your title, Wet, has both sexual and non-sexual connotations. The building pressure of sexual restraint is a theme in the book, which often demurs from direct statements about sex and sexual desire but for stretches of the book it’s also—and I don’t think I’ve summarized a book like this before—relentlessly horny. Do you see this book as exclusively about this one speaker’s experience, or as a broader representation of the pent-up sexuality of Singaporean society and/or the culture of modeling?

LD: Ha! I think there are a lot of things we’re all pent up about, and readers can bring their own experiences to the work. Of course, a big part of the building pressure is desire—to live in a world that’s less-isolated, less-burny.

RT: Wet is built out of a series of discrete vignettes—a carefully curated scrapbook of your speaker’s memories (many of which, I assume, are drawn from your own life in Singapore). The scenes shift in significance from dramatic to ordinary, serious to funny, asides to central narrative events—you never know what will come on the next page! I found it to be a highly engaging reading experience.

I’m curious how you gathered the raw material out of which you built those moments: while living in Singapore were you taking notes in a journal, which you drew from later, or do you just have a tremendous memory? Did you already have the book in mind while you were working there?

LD: I’ve lived in Singapore for several stints over the last two decades. I always kept a pocket notebook and wrote things I found interesting. I guess this is why the country makes an appearance in most of my books so far. I started this book in Singapore in 2015, at the tail end of the Southeast Asia Haze. I wrote most of the book then, and then took another eight years to develop a narrative and fine tune and adapt with the regularity of forest fires and mask-wearing. I remember 2015 had intense forest fires in BC, then I went to Southeast Asia, and it was even worse there. It really shook me.

RT: In Wet, as the Singapore air quality worsens, your speaker orders N-95 masks in bulk from Taiwan to help her and workers near her apartment breathe through the smoke. Was the Covid-19 outbreak, then, a bit of deja vu?

We’re in the window when authors’ “pandemic books” are being published, so I’m curious if Covid spurred you to move this book forward towards publication.

LD: Asians, myself included, have been wearing masks for ages. I recall wanting to wear a mask in Vancouver many years before Covid and being judged by others. I was like, I’m doing this for you! I’d like to think opinions about mask-wearing have changed, but I’m not so sure… I did think the idea of a whole population wearing masks would be a compelling image for readers, and worried that the idea would no longer have an impact now that we’ve experienced a global pandemic, but there are plenty of other things going on in the book to hopefully keep readers interested.

RT: In your acknowledgments, you mention the Singaporean organization HOME (Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics), which advocates for the rights of the country’s migrant workers. Could you talk a little about this group, and why it was important for you to advocate for Singapore’s migrant workers in this book?

LD: HOME has been around for twenty years, advocating for the rights of migrant workers. I’ve been following them for years and learned a lot about the gaps between what migrant workers require and aren’t getting. I’ve learned about the traps, barriers, and challenges many migrant workers face in Singapore, and around the world. Singapore is considered a prosperous country, but the cost of this seemingly success story isn’t shared enough. That’s also why I mentioned the writing of MD Sharif Uddin, who wrote poems and nonfiction about his experiences as a construction worker in Singapore. He also wrote a more recent book about his experience during Covid, which was particularly bad for migrant workers, who live in crammed, communal spaces.

Cross-training is key to my practice and involves me working in one discipline in order to keep my senses sharp in another.

RT: As you touched on earlier, you often combine your hybrid poetry/prose with music from your band The Deep Cove. Your first book, To Love the Coming End, was accompanied by the album To Love the Coming End of the World; your second book, One and Half of You, includes links to download three original songs; and The Deep Cove’s second album The Gift has a companion short story which you published in 2019 with Book*hug. Have you made music to accompany Wet? If so, I look forward to hearing it!

LD: The wetness is all around! From the names of my musical projects, The Deep Cove, to tidepools (who did the instrumentals in One and Half of You), watery bodies are my thing.

I had started writing some music for this book a few years ago, but then began doing more photography and decided to bring that element to the work instead.

RT: What does working in these other art forms contribute to your books?

LD: When it comes to making art, I like to think of the idea of cross-training. Cross-training refers to using various modes of exercises outside of a central activity so that other muscles in the body are engaged and balanced in strength. For me, cross-training is key to my practice and involves me working in one discipline in order to keep my senses sharp in another. In other words, cross-training keeps my artistic muscles healthy and happy. Working on one project will teach me skills that I can then go back and apply to a previous and/or future project. This keeps things interesting for me; I’m rarely bored artistically.

RT: Though you didn’t write new songs for Wet, is there a song you’ve written that might be a good match with the book, or this conversation?

LD: Here’s a song from my last book that may be appropriate: “The Sound of Waves.”

Leanne Dunic transgresses genres and form to produce projects such as One and Half of You (Talonbooks, 2021), To Love the Coming End (Book*hug / Chin Music Press 2017) and The Gift (Book*hug 2019). She is the leader of the band The Deep Cove and lives on the unceded and occupied Traditional Territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ peoples.

Rob Taylor’s fifth poetry collection, Weather¸ will be published by Gaspereau Press in Spring 2024. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.