This interview was conducted by Alix Hawley.

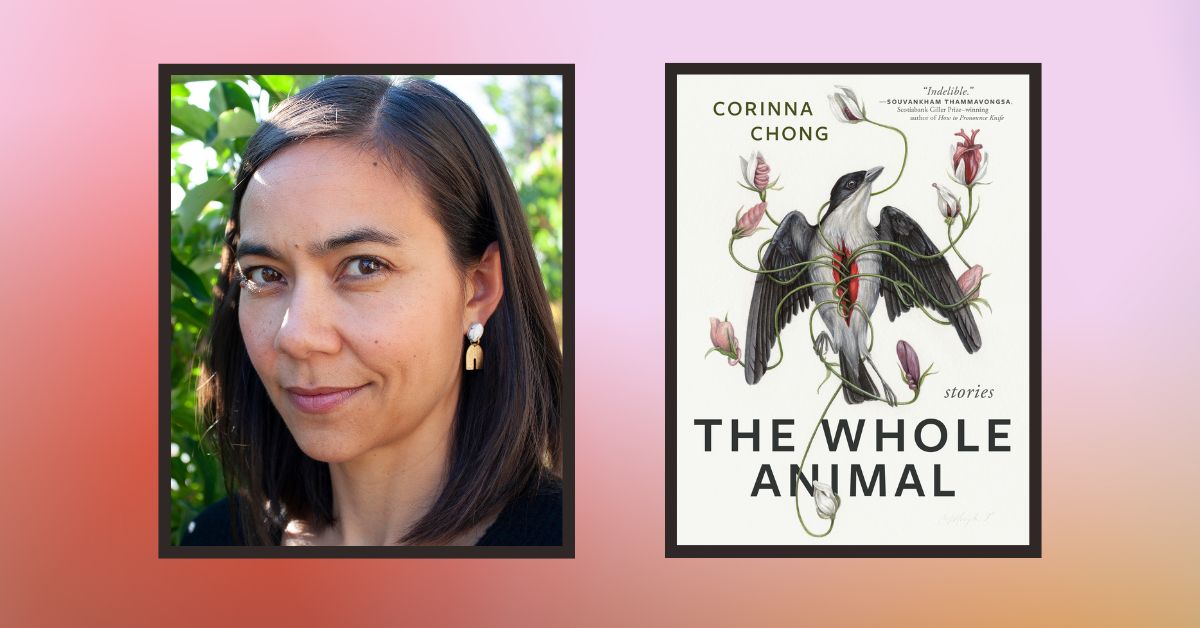

Corinna Chong’s new collection of short stories, The Whole Animal, was published by Arsenal Pulp Press in April. This conversation between Chong and Alix Hawley has been lightly edited for clarity.

Alix Hawley: Where does a story start for you?

Corinna Chong: I think most often with a single sentence, which ends up being the one that literally begins the story. The sentence often suggests a voice and a conflict to me, and then the story builds from there. So once I’m finished, I come back to that sentence as the genesis of all the ideas and all the layers I was setting out to explore. I like certain rhythms or cadences as a way to come into a story.

Speaking of rhythms, I’ve wondered if poetry is in the back of your brain when you write.

Poetry frightens me. I used to think that I was so far removed from poetry, that it was a foreign beast to me. But as I write more, I realize there’s something poetic about the way I look at language. Sound is really important to me. I think really carefully when I’m editing about those slight adjustments that change the sound.

It’s a writerly way of looking at the world—why is that person making such poor decisions?

So do you read your work out loud when you’re writing?

Definitely. I always read out loud when I’m drafting and editing. Especially dialogue. I feel it has to have a certain pace or rhythm.

You do all the different voices?

I hear them in my head!

Regarding voice, you use mostly third person in The Whole Animal. Can you talk a bit about that?

My go-to point of view is third-person limited, maybe because the writers I love the most use it: Alice Munro, and Lorrie Moore, who also writes a lot in second person, so I just hear stories in that way. I think third-person limited is more flexible than second or first person in some ways. It allows you to work with the voice of a character but also be a narrator at the same time.

So do limits interest you too? As in, how much can I say when I’m stuck inside this single person’s perspective?

Absolutely. I’m never writing omnisciently. I’m always interested in the singular perspective of a character—in that disconnect between how that character and others perceive the world, and how the character can be blind to what might be reality, and how they get so wrapped up in their own conflicts and their own insecurities that they are unable to see things from outside themselves.

Your stories often hinge on that moment, where a different light goes on for someone.

Yes. Those moments of realization that oh, things may not be the way we think they are. I love unreliable narrators too. I like to play with them also.

That makes me think of a book club I was working with the other day, whose members were very unimpressed with unreliable and unpleasant narrators. Do you set out to write about flawed or damaged people?

I do. They’re far more interesting. And we’re all flawed. It’s a writerly way of looking at the world—why is that person making such poor decisions?

The “why” mitigates the unpleasantness.

Right. I wonder always what’s at the heart of the unpleasant or harmful actions, the psychology of the characters. Often it’s an aspect of their childhood or some insecurity they’re grappling with. Probing the reason for the unpleasantness or blindness is really interesting.

I want us to understand people who are unlike us, that’s part of why we read.

What do you think of that push to make “relatable” characters?

I’m very resistant to that. I want us to understand people who are unlike us, that’s part of why we read. My students are often looking for relatable characters when we analyze literature, and I don’t think it’s the writer’s job to make characters similar to the readers, or likeable at all. Writers should challenge readers to think differently, to imagine themselves differently, to empathize. I want to be empathetic. I want my readers to feel that too.

There are a lot of children in your stories, sometimes with ambivalence about what kids are like. A lot of them are a little sinister or weird! Where does that come from?

Partly from my own childhood. I was the kid who liked dark things. I was cheerful on the outside, but really interested in darkness and subversiveness. That was private for me, from the things I read.

V. C. Andrews?

I was a Roald Dahl kid! The darkness he put into the storytelling was so intriguing to me, and so I sought it out. It also comes partly from my little brother, who is ten and a half years younger than me, and he was a weird kid who got into trouble quite a bit. Having a hand in raising him, although from the perspective of a teenager who wasn’t mature myself, was an interesting place to be. It made me think differently about kids. I’m drawn to creepy kids, but mostly the ways they can reflect adults back to them. They’re so much less filtered. When adults have to confront that, it can bring their own issues to the surface.

That makes me think of the “Kevin Bombardo” story, where the narrator says his six-year-old daughter is already a better person than he’ll ever be.

Yes. The narrator is so worried about what everyone else thinks that he unwittingly warps himself into a bad person at times. The daughter is just herself, ok with strange people, simple and accepting, although that seems impossible for the narrator.

Animals are also a big deal in your stories. Is that related?

I think it’s similar, and I didn’t realize there are so many animals in the stories until I thought about “The Whole Animal” as the collection title. They act more like images or symbols than the kids do, even though they also represent simplicity to the characters. But when the characters come up against them, the animals complicate their situations. Like in the title story, when the characters realize something difficult or deeper about themselves.

I like certain rhythms or cadences as a way to come into a story.

Your stories make me think about George Saunders, who is very good at articulating his own mental processes, and I know we’re both fans of his! In his Story Club newsletter, someone asked him recently how he knows when to throw out a draft. Saunders said he has no universal answer, but he said a story works when it’s a “tight, organic system that is at a high level of responding to itself.” I wonder if you have a sense of when a story is working or not?

I wish I knew. I have to get past the feeling I need to throw everything out! I don’t know how it’s working until I get to the end of a draft. I’m a little stubborn about not wanting to let stories go. One of the stories in the collection, “Zora in the Whirl,” I worked on for 14 years. I started it when I was an undergraduate student, and didn’t want to give it up.

Did the plot stay the same? The characters?

The plot shifted, the writing changed a lot, but I needed to keep exploring the characters, processing them. They’re still there.

Our friend George Saunders also talks about a story needing to find out what it’s arguing with itself about. I feel that in your stories, that internal tension.

I heard a great quote from Yeats recently about how arguing with others is rhetoric, arguing with oneself is poetry. That felt so true. Maybe the point at which a story starts to work for me is when I can feel that argument. The answer to the argument isn’t the point. If more layers and more questions come out, it gets better and better.

—

Corinna Chong image credit: Andrew Pulvermacher

Alix Hawley is the author of All True Not a Lie In It, which won the Amazon.ca First Novel Award and the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and was longlisted for the Giller Prize. Her second novel, My Name is a Knife, was one of Esi Edugyan’s picks of the year. Her work has also won the CBC Short Story Award and the CBC Bloodlines competition. Alix lives in British Columbia.