This post was compiled by Rob Taylor.

Throughout this year’s interview series for National Poetry Month, we’ve spoken with BC poets about their new books. Now they get a chance to share some love with others! We asked each featured writer to write about a BC poet who influenced or inspired them.

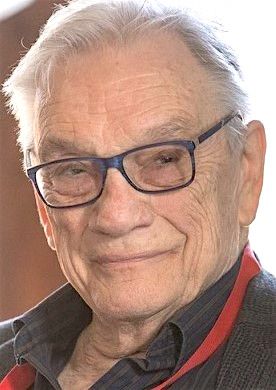

Roger Farr on George Bowering

Much of what I think I know about poetry and poetics I gleaned from writers associated with the second, Vancouver-based iteration of the Kootenay School of Writing, and through my close friendships with Aaron Vidaver, Dorothy Lusk, Reg Johanson, and Danielle LaFrance. That said, I came to the KSW with a head full of ideas I got from George Bowering, who I met as a student at SFU in 1992.

I wasn’t part of the infamous Tads group, but I studied poetry with George (and George’s poetry) for the better part of that decade and I am hugely indebted to him. George never taught “writing” as such though; instead, he would sort of annotate the history of modernist and post-modernist poetics with exceptionally nuanced (and idiosyncratic!) readings of poems he both liked and hated. One class would be dedicated entirely to decimating a poem by Frost. Another would be a line by line reading of Pound’s Cantos. Or a single sentence by Stein. Or Spicer. Or Brand. His “teaching methods” were unorthodox to say the least. It was more of a teaching-performance by someone whose understanding of the line, the syllable, form, proceduralism, etymology, history, theory, literary milieus, etc. was just staggering. Not everyone liked it. Cranking the Nihilist Spasm Band on a crappy portable turntable at 8:30 in the morning, as a way into poems by Coolidge and Baraka, is not a great way to make friends. When I told him in 1997 that I wanted to do graduate directed studies with him on Phyllis Webb, another major influence, he just gave me her phone number and told me to go visit her, which I did.

If I could only keep two of his books, and there are a lot, they would be Errata and Taking Measures. The latter is a recent selection of his serial poems, and is endlessly readable.

Dale Tracy on Eve Joseph

Eve Joseph’s Quarrels explores how one thing can turn into or be like another. It’s impossible to show how compelling each of her prose poems is without showing each connection leading to the next (and back again, and around), but I’ll try!

One poem mentions the “wonder-like,” and I think these poems are like wonder in the way that “light arcs across the room and bends at the corner like a hinge” of a “door that could open but remains closed.” For the speaker of this poem, the hinge replaces the logic that the dying follow the light. Such logical turns are the hinge of light that the poems outline while leaving closed the mystery because, as one speaker says, “these are my thoughts but not my words.” Readers can let the end of that light arc enter our minds to photosynthesize our thoughts, like the poet in one of Joseph’s poems. For that poet, “commas are hearing buds he places deep inside his ears,” that he plants there for “sprouts to unfurl” and that “he strings… on the washing line between the tree in the ear and the shelter built out of longing.” Readers can follow the lines in these poems—the mysterious line of light, the ordinary washing line—through forests we can hear growing in our minds to all the possibilities sheltering nearby.

Délani Valin on Jónína Kirton

I was completely bowled over by Jónína Kirton’s Standing in a River of Time. This book exemplifies generosity in so many ways. Kirton opens the book with an address to the reader, encouraging them to take good care of themselves. Right away, I knew I was in good hands, and the experience only deepened. The hybrid form of poetry and memoir works so well: stories unfold in the prose, and then references appear in the poetry. The echoes allow the words to sink into my marrow, and they remind me of the way in which Métis stories live inside us and unfurl when we need them most.

The generosity continues with Kirton’s cataloguing of teachers and influences in the form of epigraphs, quotes, and references. At the end of the book, I felt like I had access to manifold trailheads towards my own healing. Traditional lands are named with care throughout the book, and gratitude is given for every mentor who makes an appearance. This book came to me at the perfect time and it was good medicine that will forever have a place on my bookshelf and in my bones.

Wanda John-Kehewin on Vera Manuel

Vera Manuel used to travel around on her scooter, with her dog, Uxtpoo, in the basket of her scooter. Uxtpoo was a black, curly haired dog (I’m not even sure what type he was) who listened well to Vera and who sat patiently by her side, or in the basket, and was driven around by his chauffeur Vera! She loved that dog and he loved her. (Animals are such healers.)

Vera was someone who stood in her truth and wanted generations after her to understand the effects of colonialism on Indigenous people. Vera was born in 1948 and passed away just shy of her sixty-second birthday. She was a poet, writer, playwright, and someone who loved to teach. Her Indigenous name was Kulilu Paⱡki (Butterfly Woman). Both her parents were survivors of residential schools and she wrote a lot about those experiences and the effects of those experiences on her and her family.

The very first time I heard Vera read “Brother I cry” at the Vancouver Public Library in the early 2000s, I just sat there in my shame, trying to catch my tears with my sleeve, probably remnants of my old thinking: “Don’t cry or let others see how broken you are. Keep pretending you’re okay!” Vera’s poem was about how much sorrow she had for her brother and that is something I could relate to at the time. Her poem was so hard to listen to, and the pain was raw but she read it without a quiver in her voice. I asked her how she could write and read that without crying. She said she was able to do it because of years of healing and sharing her truth, which wasn’t hers to carry. I decided then and there I would “stand in my truth.” If this woman who had cancer scooting around town in her scooter with her dog in the basket, wearing her oxygen as she read, could stand in her truth… I would too. She gave me a gift that day. She told me don’t be ashamed to cry.

Jane Munro on Daphne Marlatt

Daphne Buckle was my first real live poet friend. She went through North Vancouver’s Delbrook High School a year ahead of me. We painted posters for student council elections in her basement. In her final year she was editor of Delbrook’s newspaper, the Hilltopper, and asked me to be her assistant editor. Following in her footsteps, I became its next editor.

At UBC, Daphne joined TISH—the remarkable group of poets instrumental in bringing Duncan, Creeley, Olson, and Ginsburg to campus. Dazzled by amazing readings to overflowing crowds on idyllic summer evenings, I read and read, parsed their poems.

Three years later and married, Daphne to Alan Marlatt and me to Jock Munro, we coincidentally converged at Indiana University. The four of us took Wednesday night beer breaks in a Bloomington pub and drove in Daphne and Al’s VW beetle down the Blue Ridge Mountain parkway. I saw wild rhododendrons in bloom on mountain slopes. Daphne was assembling a book. I loved her poems enough to do line drawings in response to them, which I liked but didn’t keep. What I did keep some years later was a draft of Daphne’s Steveston—poems which no doubt influenced my newest book, False Creek.

Through many changes and books, we’ve stayed in touch. Daphne has inspired and encouraged me. Her intelligence, courage, compassion, hunger for understanding, humility, spiritual and artistic discipline—as well as her explorations of poetry, writing, friendship, and womanhood—have enriched me.

Tāriq Malik on Tolu Oloruntoba

I find my fellow BC poet Tolu Oloruntoba’s debut poetry collection The Junta of Happenstance dazzling. It won the 2021 Governor General’s Award for English-language poetry and the 2022 Griffin Poetry Prize. The book stuns me with Tolu’s mastery of imaginative wordplay, free association, and courageous flights into darkness, venturing to the edge of comprehension, where, as he puts it, he “risks clarity.”

The subjects of his distinctive self-taught poetry range from the surreal unpacking of the onion layers of colonization-trauma and the ambiguities of race identities to challenging power’s raison d’être amongst the downtrodden and the “urban precariat.” I can’t wait to read more of his work.

David Zieroth on Tom Wayman

Tom Wayman’s poetry has been a companion since we were published together in an anthology of four poets (with Susan Musgrave and Paulette Jiles) called Mindscapes, edited by Ann Wall (Anansi, 1971). The warmth of his friendship and the humour, irony, and rage in his poems continue to inspire me. I am thinking now of Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time, (Harbour, 2020). His poems of the natural world inspire me in the way they show us what we might have not quite seen, as in his chapbook The House Dreaming in the Snow (The Alfred Gustav Press, 2020). His long record of encouraging other writers, including me, is equally inspiring. His advice to poets has often been to send their poems out into the world, as he himself has done and continues to do, so they appear in Canadian and American journals on an ongoing basis. His is a life in poetry I applaud and admire. His poems are always welcome on my bookshelf because, as he writes on his website about his forthcoming book Out of the Ordinary (Harbour, 2024), “… our simplest everyday acts create the astonishing and complicated society in which we exist: a world that, despite its sorrows, can—at times—be overwhelmingly beautiful.”

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸ was published by Biblioasis in 2021. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.

One reply on “Seven BC Poets on the Writers They Love”

[…] Many thanks to Tāriq Malik for choosing Tolu Oloruntoba and THE JUNTA OF HAPPENSTANCE for this list of Seven BC Poets on the Writers They Love, compiled by Rob Taylor. “The book stuns me with Tolu’s mastery of imaginative wordplay, free association, and courageous flights into darkness, venturing to the edge of comprehension, where, as he puts it, he “risks clarity.”” Check out the entire list here: Seven BC Poets on the Writers They Love […]