The following interview is part seven of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

ᐁᒋᑫ ᐃᐧᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ

ᓄᐦᑯᒼ went to residential school

ᒧᓲᒼ went to war

ᐊᐧᐦᑯᒪᑲᐣ hung himself

ᓂᑲᐃᐧᐢ shot herself

ᓂᑲᐃᐧᕀ drank herself gone

ᓅᐦᒑᐄᐧᐢ died with a bottle

ᓄᐦᑕᐃᐧᕀ didn’t want to die

ᓂᑐᑌᒼ lost to the streets

ᓂᑐᑌᒼ finally passed away

ᐊᐋᐧᓯᐢ lost to the system

ᓂᔭ witness and survivor

ᐋᒋᒧᐢᑕᐁᐧ

Reprinted with permission from Spells, Wishes, and the Talking Dead ᒪᒪᐦᑖᐃᐧᓯᐃᐧᐣ ᐸᑯᓭᔨᒧᐤ ᓂᑭᐦᒋ ᐋᓂᐢᑯᑖᐹᐣ mamahtâwisiwin, pakosêyimow, nikihci-âniskotâpân (Talonbooks, 2023).

Rob Taylor: The title and section titles of your new book, Spells, Wishes, and the Talking Dead ᒪᒪᐦᑖᐃᐧᓯᐃᐧᐣ ᐸᑯᓭᔨᒧᐤ ᓂᑭᐦᒋ ᐋᓂᐢᑯᑖᐹᐣ mamahtâwisiwin, pakosêyimow, nikihci-âniskotâpân, are all presented in three ways: in English, in Cree syllabics (ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ), and in romanized Plains Cree (nêhiyawêwin). Though the majority of the words in these poems are in English, occasional words are presented in Cree instead of English, with a ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ nêhiyawêwin glossary at the back for English speakers. Why did you make that choice, and what effect do you hope for it to have on your readers?

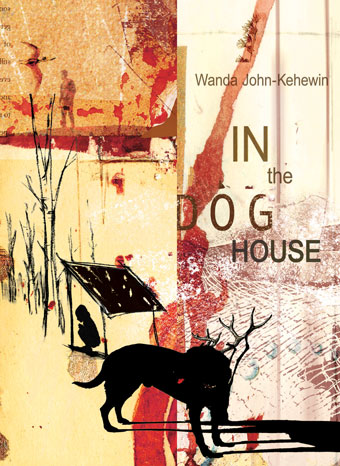

Wanda John-Kehewin: I made this choice to sort of decolonize language and as a way to “take it back.” Since the very first book I wrote, In the Dog House (Talonbooks, 2013), I’ve had this unsettling feeling that’s sat with me throughout my time as a writer who publishes things. I’ve really tried to figure it out. I finally realized that the unsettled feeling I had was that I was a fraud as a Cree poet because I didn’t write or speak my own language which is, or I should say “was,” Cree.

I was writing in English using English tone, diction, sounds, rules of grammar and syntax, which is why I wanted to break the rules of syntax and grammar in a way that helped me to make sense of the emotions I felt. I wanted people to wonder and to feel the “foreignness” of another language, and yet still be curious about it.

You do that so well, especially in poems like “ᐁᒋᑫ ᐃᐧᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ.” I feel like I completely understand that poem, while also not being able to read a large portion of it. And I’m left curious for more.

In the book’s preface, you write of the guilt you feel “as I write in English and struggle to name emotions, places, and things in ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ nêhiyawêwin.” Over the course of researching and writing this book, did you find it became easier to express yourself in ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ nêhiyawêwin?

I think because life and time is so limited on this Earth we must choose what is important to us to learn, and learning Cree at this point would be a challenge between working to survive, writing to thrive, and parenting to transform the past (trying, always trying). I think writing this book, and doing the research, I learned to make peace with my past in order to make way for the future. Yes, I could grieve that I did not speak or write in my language, but I could honour it and perhaps learn Cree one word at a time. I still struggle pronouncing it, trying to sound it out as it is written and sometimes (most times) saying it in a way that fluent Cree speakers would not understand.

It felt foreign and still feels foreign to try to sound out Cree words, like I am trying to learn a second language when it should be my first.

Do you now feel, at least, a little less guilty about your struggle?

Yes, especially with the research. The book opens with a timeline in which I tried to make sense of my own “timeline” and how my family systems were affected by colonization, or should I say the ripple effects of contact. “Colonization” is such a blanket word but it’s definitely a term that encompasses everything that happened to Indigenous people: the ripple effect of circumstance leading to the near destruction and decimation of Indigenous cultures, traditions, and languages.

In the preface, you say something interesting about colonization in relation to your writing: “writing acts as a therapeutic medium for making sense of intergenerational trauma resulting from colonialism.” You also write that you “use poetic elements” to try to “figure out what language means to poetry and what poetry means to language.”

Could you talk about these two goals of your writing? Are there ways in which they are distinct from one another, or do you think of them as a shared goal, united by the impacts of colonialism on both peoples and their languages?

I wanted to use poetic elements like tone, diction, syntax, meter, form, etc. to weave my way through discovery and what it felt like to write in another language which wasn’t my own, but which was the only language I spoke. It felt foreign and still feels foreign to try to sound out Cree words, like I am trying to learn a second language when it should be my first. I have talked to many fluent Cree speakers, and they have all said that the Cree language is descriptive. For example, aski pwawa is Cree for potato but does not translate to just potato; it actually translates to “Earth’s egg.”

The Cree language is poetic and changes over time. For example, a table is not just a table. In English when we say table, we all see a table, we all know what a table is. But in the Cree language mîcisowinâhtik loosely translates to “something made out of wood that we eat on.” So the word “table” had to be descriptive to describe what it is used for.

Imagine we all went around describing things without using the word; a table wouldn’t be a table but something made out of wood that we eat on. A potato wouldn’t be just a potato but an Earth egg; which conjures up more of an interesting image? Perhaps a broken heart would be something like grieving the loss of a loved one who still walks the Earth, or grieving the loss of a loved one who no longer walks the Earth. That is what poetry is, it is description, it is imagery, and it is relatable to the human experience.

What a wonderful, and yes, poetic, way to think about the world around us. In addition to your work between languages, you also show a broader interest in formal experimentation. In the Dog House featured a number of concrete poems (a spiral, a diamond, a wine bottle and glass…), and your interest in playing with shape seems to have only grown since then.

In your new book, alongside more traditional free verse poems, we find list poems (like “ᐁᒋᑫ ᐃᐧᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ”), prose poems, blackout poems, contrapuntal poems, a golden shovel, an eleven-page essay, poems with words replacing punctuation, poems with surprising use of slashes, etc. It feels like hardly any two poems are written in the same mode.

Thanks for explaining to me what I did because I didn’t really think about the differences! I am giggling to think how different my writing is from my first book. The poem in a spiral, “Chai Tea Rant,” had such emotionally upsetting content for me to talk about, but I could express it better when it was hard to read. It was like being able to stand in my truth and to speak it. Those who took the time to read it were meant to read it, and those who skipped it because it was too hard weren’t meant to read it. I think concrete poems offer a container to speak and stand in one’s truth, and it’s up to the reader to decipher it or not to decipher it.

I love that. In a sense you’re saying, “I had to live through this, but you’re welcome to hear my story if you’re willing to work for it.” What inspired you to range even more widely, formally, in this book?

My first book was written in a depression, the second at the tail end of the depression and this third book was written in a time where I finally understood how all the negative things that happened in my life were bigger than me, even bigger than my family. It became more of a macro-problem and not just a “me” problem. For years I questioned myself, “Why can’t I just get over it? Why can’t I just forget about it? Am I crazy? Why is my life so horrible compared to others? Why? Why? Why?” I had so many unanswered questions and the only way I could process the past, present, and even the future was to write about it. Writing has always given me a better understanding of any situation. Writing, for me, is truly a gift and has helped me come to terms with the past. (That and years of counselling!)

The idea of self-image is easier to digest when someone else shows you their vulnerabilities and you find out you still admire them, and even admire them more because they stand in their truth and make space for you to stand in yours.

That makes a lot of sense to me—each new question you unpacked required a new shape. Considering how formally diverse the resulting book is, did you always imagine it as a single collection, or did you bring the disparate parts together later in the process? Did you consider writing a more traditional prose memoir?

While doing my MFA at UBC, I wanted to create space to write about things that troubled me, or things that I wanted to figure out, or even things I wanted to imagine. This collection became the spells (things that mystified me), wishes and the talking dead where I imagined my ancestors could speak through me or where I could have the hindsight to feel the emotional pain and turmoil they must have gone through.

In my first book, I had a poem called “Colonial Pest-Aside.” That was such a hard poem to write, to re-read, and to edit to get just right. I imagined what it was like to be “force fed words of righteousness,” to be called savages, and how much pain and suffering that would cause all the ancestors hearing it while still praying for future children to have a chance to fall in love with their culture and themselves as perfect creations just as they are. I guess this collection is an autobiographical book of poetry.

I think my next book will be a memoir.

Ah, I sensed that might be the case. I hope you write it.

Some of your formal experimentations brought to mind other female Indigenous poets, notably Layli Long Soldier and Jónína Kirton. Could you talk a little about the role Indigenous women poets have played in helping you see what might be possible in your own work?

While doing my MFA, one of our assignments was to do a presentation about a poet we admired. My instructor, Bronwen Tate, suggested I look at Long Soldier’s work. I was fascinated by Long Soldier’s ability to write powerful, short-lined poetry and also to be able to talk about the harsh truths of history in a way where she did not care about the consequences of her words. This set my writing free. At the time I still wasn’t able to “blaspheme” the church or the government for fear of some sort of repercussion (I’m not sure what). I had the opportunity to both read Long Soldier’s work and interview her over Zoom. I was in awe of her and her work. I thanked her profusely for her time and probably asked all the wrong questions! I admired her ability to “stand in her truth” and to put it on paper in such a powerful way.

Jonina Kirton is another poet who has taught me to keep moving forward and to “stand in my truth” from her ability to be vulnerable in her work. She shares her vulnerabilities so others can feel comfortable in theirs.

A recurring theme in your book’s first section, “ᒪᒪᐦᑖᐃᐧᓯᐃᐧᐣ mamahtâwisiwin Spells,” is negative self-images. “I am fat / I am ugly / I am dumb / I am clingy / I am boring / I am worthless / I am a worthless Indian // I wear my trauma garlic / to the vampire party,” you write in “Monkeys in the Brain.” Did writing this book, or writing poetry in general, help you shape your own self-image in a more positive way?

These are things I told myself for years. I think as human beings trying to be like the others in school, at work, at church, online, etc. leaves our state of humanness with “monkeys in the brain.” Growing up with dysfunction and trauma, I lost myself in books I could escape into and not once did I read about productive “Indians” or smart “Indians” or even beautiful “Indians.” I learned to see myself as not good enough. If only I was white or had blue eyes, or blonde hair, or was fatter (I was very skinny as a child) or skinnier (weight gain in my later years), or had whiter teeth, better teeth, better skin… the list went on. The monkeys in my brain partied a lot! Learning about the history of Kanata with Indigenous People, healing through reading, self-reflection, and counselling, meeting the people I did, and allowing myself to be vulnerable has really helped. I’m now able to let that vulnerability show without judgment. When the monkeys in the brain are partying, I tell them we are ok, I got this, and that I can take care of them. Those monkeys in the brain are just fear, and have kept me alive.

What effect do you hope this book will have on the self-image of young (or old!) Indigenous readers?

I think the idea of self-image is easier to digest when someone else shows you their vulnerabilities and you find out you still admire them, and even admire them more because they stand in their truth and make space for you to stand in yours (like Vera Manuel). When someone’s words resonate with you or bring up emotions which you forgot you had, or perhaps thought you’d figured out, you realise you are still hiding. It helps others to be brave and accept their humanness as well. We are all spiritual beings living the human experience and if we can navigate life knowing our humanness is flawed and that’s okay, we will be okay.

In the book’s closing section, “ᓂᑭᐦᒋ ᐋᓂᐢᑯᑖᐹᐣ nikihci-âniskotâpân The Talking Dead,” you write about your Great-Great-Great Grandfather Chief Kihiw. Could you tell us a little about him?

My uncle Victor, who passed away, was a kind, generous, and compassionate man who fully supported my educational pursuits. I was proud to share with him what I was doing because he would tell me he was proud. Uncle Victor loved to talk to me about oral history, which was not in books but had been passed down to him. Chief Kihiw was not in many historical records (I did find him in Census records, though). My Uncle Victor would tell me about the friendships between Chief Kihiw, Chief Big Bear, and Chief Sweetgrass, and about who we were related to and where everyone came from because “back in the day” people were scattered. Uncle Victor told me of a time when the three chiefs would meet to discuss not signing the treaties, but they were starving. This relationship can be seen in my graphic novel series by Portage & Main Press, Visions of the Crow.

Writing has always given me a better understanding of any situation. Writing, for me, is truly a gift and has helped me come to terms with the past.

At one point you write that he is “alive in my daughter.” How do you see Chief Kihiw in her? How do you see him in yourself?

When I say Chief Kihiw is alive in my daughter, I mean the blood memory. I think a part of culture is also the feeling we have with cultural objects as well as our relationship with place. I travel home once or twice a year to Kehewin reservation and it is home. It is a place that also holds so many past memories of suffering, but it is also a place of love. The love of the animals that live there, the family that is still struggling to survive (survival mode), the laughter that happens to alleviate the pain, and the want to ease the pain of another through small deeds. I see Chief Kihiw in myself as a word warrior who has an obligation to make things better for future generations and my gift is writing, so that is what I am trying to do.

On the subject of that gift, in “Dead Porcupines Aren’t Just For Jewellery,” you write “I don’t make jewellery. I don’t create art. / I don’t Powwow dance. / I write poems.” Could you talk a little more about this—about how you feel your writing poetry fits within more externally-recognized Cree arts (beadwork, powwow dancing, etc.)?

I think writing poetry has given me the ability to make sense of the world around me. Pre-contact, everyone would have had their “roles” that helped create a circle of life. I don’t mean roles in such a predetermined, forced position, but more in a communal context where each and every person who is part of a community has a responsibility to that community. We all do not have the same strengths or gifts. A baby is born, becomes a child, then an adult, then a knowledge carrier or, in contemporary terms, an Elder. In each of these stages of life, there would have been hunters, gatherers, drummers, storytellers, child minders, clothing makers, and this list goes on. There would have been navigators as well. I think I would have been a storyteller. Poetry is an act of telling a story. A storyteller can hold an entire lifetime through their choice of poetic elements. A beginning, a middle, and an end, that’s what life is.

I admire your careful attention to the tools of a storyteller, especially the language they use. At the end of the book you write, “one day I hope to write a poetry book in nêhiyawêwin,” and that the process of moving more and more towards writing in ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ nêhiyawêwin is like “decolonizing myself one word at a time.”

This reminded me of Kikuyu novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who published the book Decolonising the Mind shortly after his decision, in the late 1970s, to write his books in Gikuyu instead of English. On the subject, he wrote that switching to local languages would force “those who express themselves in African languages to strive for local relevance in their writing because no peasant or worker is going to buy novels, plays, or books of poetry that are totally irrelevant to his situation.”

If you one day write a book of poems entirely in ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ nêhiyawêwin, do you think it will change, in some way, the nature of what you write about, or how you write it? Will you strive more for “local relevance,” and if so what do you think that would look like?

I have not heard of Decolonising the Mind, so thank you. I will add it to my list of things to read. The list keeps getting bigger and bigger.

If one day I do write a book totally in nêhiyawêwin, I imagine it will be a short book, really thinking hard about the scope of this considering I do not speak it. Will it change the nature of what I write about? I do not have an answer but I do know coming out on the other side of trauma has already changed the way I write. Perhaps a lot of things will change the way I write, even the lack of time changes the way I write. So I think a book of Cree poems will be in all Cree reserve libraries and universities as one of those “oddities” or one-offs. Someone may write a paper on it trying to figure out why a poet would do the painstaking labor of writing a poetry entirely in Cree without being fluent in it. I think this could be done with a Cree translator translating it as best they could, because according to every fluent Cree speaker I have spoken with, the Cree language is so descriptive and sometimes so hard to describe in English. A joke in Cree can make a group of fluent speakers laugh but when they try to translate it in English it isn’t funny anymore and the person trying to translate it becomes flustered. The joke becomes lost—so would it be the same with poetry?

Wanda John-Kehewin is a Cree writer who came to Vancouver, BC from the prairies on a Greyhound when she was nineteen and pregnant—carrying a bag of chips, thirty dollars, and a bit of hope. Wanda has been writing about the near decimation of Indigenous culture, language, and tradition as a means to process history and trauma that allows her to stand in her truth and to share that truth openly. Wanda has published poetry, children’s books, graphic novels, and a middle-grade reader with hopes of reaching others who are trying to make sense of the world around them. With many years of traveling (well mostly stumbling) the healing path, she brings personal experience of healing to share with others. Wanda is a mother of five children, two dogs, two cats, three tiger barb fish, and a hamster.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸ was published by Biblioasis in 2021. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.