The following interview is part six of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Devín Castle

a ruin above the confluence of

the clear Morava with the deeper

darker Danube it fails to influence

and where men watched from heights

while water flowed past and past

endless in the possibilities of seasons

and terrors but also hours when

a guardsman’s attention drifted toward

his night meal of meat, nuts or soup

while the wind blew his way,

the smells of mud and freshets spilling

near fresh burial mounds

and as he fingered his iron weapons

one slipped from his animal belt

to appear much later among amber

in an exhibit around which students

cluster, perhaps one of them aware

how time has thrown him up here

among his smoking, joking peers

to speak Slovak, to wear jeans

to find his body a mystery he worries

may never be easily understood

under my hand the cold rock that forms

this wall is solid, but I know better:

Miro takes my photo, which becomes

a memento mori when days from now

I discover it has remained unchanged

in my camera – still the same squint

the grey sky behind showing no sign

of Perun, god of lightning and thunder –

whereas this very hand is less

the sure thing, and yet it serves still

to crumble more stone

into the river below as I reach out

to my friend’s hand and climb down from

the bastion – and so we return to our own

sensibilities, heartened here among

scrambling teens ablaze, the beauty of

a summer evening before them

sunlight slanting into warm gold

just at that moment when it sinks –

which I might notice more than they

Reprinted with permission from the trick of staying and leaving (Harbour Publishing, 2023)

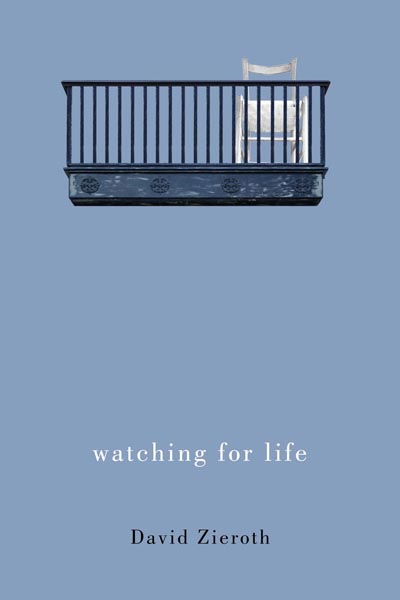

Rob Taylor: The “trick” in your new collection, the trick of staying and leaving, is performed by the Danube river, which stays fixed in one place while also flowing constantly away. You’ve gone and published two books in six months: Fall 2022’s watching for life, set on a balcony in North Vancouver, and this new book, set in Slovakia. Despite taking place half a world apart, the two feel, in many ways, like the same river. Both combine a still observer and their ever-moving observations (in the first of the Slovakia poems you position the speaker “at a second-floor window seat,” mirroring the balcony in watching for life). Do you think of these books as a shared gesture set in two different places, or is there some change in the spirit of the writing from place to place? Perhaps a change in the spirit of the author?

David Zieroth: In both books I think of the speaker as a careful observer, sometimes distanced; and yet the spirit of the two books feels quite different to me. While the trick of staying and leaving comprises all pre-Covid poems except for one (“driving country roads in Slovakia”), the poems in watching for life were written during and after (can I say after?) the pandemic. The Slovak poems would have been published earlier except for the arrival of the uncertainties spawned by Covid, so the autobiographical order is not the same as the publishing one. For me the Slovak book feels more open because I’m out in the world exploring and experiencing with people I admire and love. The balcony book feels a lot lonelier. It’s just me looking out and intuiting connections with others.

Ah, I hadn’t made the Covid connection. The tonal differences between the two books make a lot more sense to me. Still, I feel they hold a great deal in common.

I remember reading a quip from Michael Ondaatje who, when asked about something in his poem, said something to the effect that if one little nuance shifted it was all different. I admit to not having a larger view of how these two books might be similar, but I can easily see them as different. Then again doesn’t every poet feel that the last thing he wrote is the masterpiece that practically annuls all previous work? Perspective on my past work is not one of my strengths. I have a handful of readers (some poets, others poetry lovers) who read my poems in manuscript, and they are renowned for their truth telling. Sometimes what I thought to be pure genius is greeted with cool respect but little warmth or pleasure, whereas a poem I hardly noticed is applauded generously. Which just goes to show you what I know about such things, eh?

Ha, I think that’s true for all of us. It’s much easier for me to ask you questions about changes in your writing style than to answer those same questions myself. So let’s stick with you! Over the years you’ve developed a distinct style, used in both these books: one or one-and-a-half page poems composed of 6-10 syllable lines, without capitalization or periods. Commas, too, are used sparingly at the end of lines—only seven in total across both books (~2,000 lines)!

Many elements of this style are present in your poetry all the way back to 2006’s The Village of Sliding Time, and perhaps further, but it didn’t seem to become your exclusive mode until 2014’s Albrecht Dürer and me. Could you talk a little about the evolution of this style?

Oh, punctuation, my former lovely chains! I like your comment about my “evolution of style,” which I think is accurate. I don’t recall making a deliberate decision to drop punctuation in the way I have. What seems to have happened is that the intensity of the incoming poem requires so much attention that I’m in a rush to get it down before it passes off into the ether, and so it’s all about the exact words and rhythms in the words themselves. The effect may be what Miranda Pearson calls “mesmerizing” on the back of the trick of staying and leaving. I’m less concerned about how the reader will manage stepping through the words, and while I do make an effort to smooth their journey through to that moment at the end when all is revealed, so to speak, the lack of normal punctuation can make that experience sometimes just a little tricky. That’s not my intention, but the reader must pay close attention, especially when the language appears so everyday at times.

I write to find what the initial idea or inspiration wants me to find, and I feel this process not only creates action on the page but also is the most exhilarating and exciting in my life, and also the healthiest.

What does having one consistent approach to a poem’s form free up for you in your writing?

Leaving capitals and periods and sometimes other bits behind is freeing. I have felt closer than ever to that ineffable thing that happens when the words arrive, and I want no shackles near.

What has writing without periods, capitalization, and end-of-line commas taught you about rhythm and pacing in poetry?

Perhaps it’s like this: when I went to a naturist beach in Croatia with my Slovak friends for the first time I was a tad shy and concerned, and then when my clothes were off and so were everyone else’s I never felt so free and so relaxed.

Ha! Yes, that sounds right. Though I don’t think I agree with you that your style makes it tricky for readers—I think the reader is equally unshackled (regardless of their opinions on nude beaches). This connects to what is, to me, the defining trait of a David Zieroth poem: motion. Even if the scene described appears mundane, we are always moving seamlessly through it: the camera-work of the poem captivates us as much as what that camera is pointing at.

In “Devín Castle,” for instance, we move so effortlessly from the past to the present, and from crumbling stone to crumbling hand. (If your poems were films, I sense they would be filmed in one unending shot—panning, sweeping, rising—like Birdman or 1917). I suspect that, in part, this has to do with the punctuation choices discussed above, but also goes beyond that. Perhaps there’s a chicken and an egg here—the fluidity of form and content. Could you talk about motion in your poems? Does how a poem moves matter more to you, in some ways, than what the poem says?

Motion, eh? Or is it ease of movement?

Yes, steady internal movement from image to image, thought to thought (even if the speaker is utterly still on a balcony). And with no periods anywhere to slow that flow.

I have not thought of my poems in this way, but it’s true my concern is to keep the poem moving, to present visuals and thoughts and feelings all together so the reader has no desire to pause and put the poem down and reach for a cheezie. It’s also true that my poems often start in circumstances that are generally easily recognizable and then they veer elsewhere, taking us into something equally recognizable but not expected, something revealed in the speaker that perhaps he himself is startled to discover right there before him. That following the golden thread in blind faith and always with the hope (and even the expectation, which is not the same) that ahead lies the understanding and experience which until that very moment did not exist anywhere at all.

Perhaps I might put it this way: I write to find what the initial idea or inspiration wants me to find, and I feel this process not only creates action on the page but also is the most exhilarating and exciting in my life, and also the healthiest. I recall often how my family back in the busy days when we were all younger would kindly hope that I might take my grumpy self away for an hour to write in order that I may return to them as my more genial self, a little clearer and cleaner having dipped my soul into the river that flows through me when the writing is good.

Wonderfully put. I’d be remiss to conduct an interview with you without asking about the Alfred Gustav Press, your subscription-based chapbook press which I’ve long believed to be Canadian literature’s best kept secret. Publishing 6-8 chapbooks each year since 2008, you recently surpassed 100 in total! I want to express my gratitude for all that work. What has editing and publishing all those manuscripts taught you about compiling your own?

I’ve written about The Alfred Gustav Press elsewhere, so I won’t comment about the press itself here except to say it’s a labour of love that five people (not counting the poets) are happy to continue. What have I learned? I like it best when a poet sends us a large handful of poems in a submission out of which we can then find the chapbook. I already knew and have learned again that it’s so difficult to see one’s own work. When I am the poet gathering together poems into a manuscript, I look first at the concentrated moment in each of the poems and not so much on how they may link with others in image or action. It’s then that I call on my friends to tell me how they see the arrangement and the order, and it’s their understanding and wisdom I rely on for the final presentation before sending it off to a publisher (where again further shape changes can occur).

Let’s talk a little about the particular nature of each of these books. In its cover, jacket copy, blurbs, etc. the trick of staying and leaving is pitched as a book about Slovakia, but more fundamentally it feels like a book about friendship. I could imagine the book existing without traveling to Slovakia, but I couldn’t imagine it without Miro and his family, and the ways you were able to see yourself anew through their eyes. Could you tell us a bit about Miro?

I met Miro ten years ago in a coffee shop in North Van. We hit it off right away and soon were friends. He was here from Slovakia for a few months to help his daughter adjust to attending school where she was learning English and our Canadian ways. Miro and I spent time together walking around the city learning English and Slovak words. He has returned here a few times since that autumn of 2013, and I have visited his home several times as well. Covid-19 made a huge difference to his life (more than to mine, I think), and in spite of travel restrictions and upheavals, we have stayed connected. Now the English he learned here is slowly disappearing (just as the few Slovak words I learned then are slipping away). Today he’s the entrepreneurial energy behind a thriving physiotherapy clinic in Bratislava. I will be seeing him and his family and friends again this coming summer. We often take a road trip to different parts of Slovakia, and he’s been a wonderful guide to places tourists would not likely see.

I believe we are given only a few themes that we must work through over and over again, and awareness of death in life is one of them for me.

How did Miro help guide you to this book?

Because of his friendship, I have learned to see worlds new to me and to question old, even unconscious, assumptions in new ways. I am also among the greatly fortunate because my daughter and her family live in Vienna, and Bratislava is only an hour away by bus, Vienna and Bratislava being the two closest national capitals in the world. the trick of staying and leaving is about both family and friends and about the kind of understanding that comes with new experiences in new territories/countries.

In the book you write, of learning Slovak, “even the most polite / cannot always keep mirth / from erupting / when I speak, my mouth / filled with too much or not enough.” Language being “too much or not enough” feels like the poet’s perpetual challenge: we are always trying to get the world down in words, but we’re never quite able. Did you feel a poetic familiarity in being lost in a language? What did starting over in another language teach you about writing in English?

I am always lost in Slovak. Like any language it’s very complex: masculine, feminine, gender and nuances well beyond me. I really only have a handful of words I can say with any tonal accuracy. I love the music of the language and enjoy hearing my friends talk (the younger generation are willing and apt translators). Perhaps more importantly, I never understand English so well as when I see others struggling with its pronunciation and many idioms. In some perhaps forgivable way I didn’t grasp the challenge of English. I was raised with relatives who spoke German to each other, and I now have grandchildren who speak German, and yet I seem to have little capacity for other languages. I was often told that, because I heard another language as a child and because I was a wordsmith, surely I would be able to pick up another language easily. Such are the myths my experiences have dispelled. I now have a greater respect for those of us writing in English with all its snaky “s” sounds, and there’s no doubt I have much greater appreciation of the efforts of Canadians who are learning English as their second language. And any experience of the nuance of language gives a heightened awareness of the word.

In writing about a foreign place, an author must feel conflicting pressures: to be both highly present in that place and record it accurately, and also to consider their “home” readership, for whom some level of explanation/translation will be necessary. The author has to think here and there at once. How did you balance the two in writing the trick of staying and leaving? Did you strike your particular balance in the initial composition, or did you grapple with the issue of audience only during the editing process?

I’m operating intuitively when it comes to the audience. In the time of writing the poem, the initial inspiration can mean minutes (with revision lasting hours or indeed much longer), and the urgency and energy of the poem doesn’t allow me to think much about who will be reading the poem, if and when it reaches the public. In general, I try not to think of audience when first writing a poem as awareness of audience as a presence over one’s shoulder impedes the flow of feelings into words. What I wanted to do in the trick of staying and leaving was convey the joy and bewilderment that can be experienced by any traveler in a foreign land. Perhaps I am somewhat equipped for this process by a love of these people and places and by a long-ago undergraduate degree in history that enables me to have a perspective with a longer than usual time frame. Perhaps there is another trick in this staying and leaving: being in the here and now and also back there at home intuitively with that audience.

watching for life is a book set entirely “back home” in North Vancouver. Its poems teem with rain, fog, gulls, crows… In this, and also in their meditative movement, they often reminded me of Russell Thornton’s poetry (perhaps especially his book Birds, Metals, Stones and Rain). Thornton is thanked—along with five others, that “handful of readers” you mentioned earlier—in the acknowledgments of both books, and blurbs them both. How have his poetry, and his poetic eye on your work, shaped your writing, and your thinking about North Vancouver?

It’s not surprising that Russell’s poems come to mind when you read watching for life. We share the same climate, and while I’ve lived in North Vancouver longer than anywhere else on earth, I did not have the blessing of being born here as Russell did, and the rain in his poems speaks in its mother tongue. Russell is a friend and a neighbour and one of the smartest people I know, as well as a poet whose awareness of poetic traditions I admire and envy. He has been a very helpful reader of my poems. But he writes in a way that is very different from me, much more in the ecstatic vein of poetry than I do. His instincts and methods are not mine or vice versa. I don’t think he’s been much of a poetic influence at all, even as I love his poetry. I’ve long ago given up trying to do what I admire in other poets; I have plenty simply trying to do what I do. But Russell has certainly helped me to see my poems more clearly than I might otherwise have had I not had his counsel at times.

In watching for life, while dreaming of Paris from North Vancouver, you write “sometimes I… think / hard about how I came here and not / to some other, more beautiful, famous / place.” Yet in your travels you chose to devote such time not to France or Italy or Greece, but famous-adjacent Slovakia (the North Vancouver of Europe?). What do you think it is that compels you, despite competing urges, to these edges instead of the centres?

I was raised on a farm in Manitoba, far from any centre and yet central to everything I was for years and which in some ways is still active in me. Slovakia initially attracted me because of the friends I made who were from there. No one in Bratislava is very far from the countryside. It’s the central European capital most likely to be overlooked. I find a molecular comfort in places less touted, where I might rediscover a bit of that person I once was in the way he looks at what hasn’t suffered too much from touristic photo-erosion. Perhaps the real connection is between Manitoba and Slovakia, and perhaps it is possible that similarities between backgrounds drew me unconsciously to Miro. Certainly I enjoy the rural world there and feel resonances of farm life not far from the city. I laughed and enjoyed the time we were stuck driving on a country road behind a load of manure that after the first few minutes caused us to roll up our car windows that until then had been offering pure summer air on the road to Orava.

Perhaps there is another trick in this staying and leaving: being in the here and now and also back there at home intuitively with that audience.

Images of falling or flying off precipices recur in both of your new books. In a poem in watching for life, you write “I’m learning to die by seeking always to live,” and that duality seems ever-present in both books: the fall and the flight. Could you talk a little about the role death (and its accompaniments, fear and clarity) played in writing these books? Was its influence the same in each?

Perhaps because I was born in November I was aware early on of the dying of light. Perhaps because I was raised on a farm with the natural birth and death of animals, I grew wary of living as if death didn’t exist. And that flying, that jumping off precipices in the poems, creates what surely everyone feels: something of that pull, that attraction to lift off from our heavy-footed pedestrian selves and to fly, even if only for a few minutes, the waiting death be damned. Like other writers I believe we are given only a few themes that we must work through over and over again, and awareness of death in life is one of them for me. That theme in watching for life is, I think, more sharply expressed than in the trick of staying and leaving because in the former book I was more isolated during its writing. Of course one doesn’t want to be morbid because such a state would annul the joy of living, of which there is plenty: think of the friendships I have experienced, the new places I’ve seen, the pleasure I’ve relished in travel, the love received and given. But there is always death to return to, like a comfortable bed at the end of the day’s journey. One might as well grow accustomed to what’s waiting, and what better way to do that than to turn one’s thoughts in that direction now and then as one often does before sleep.

Your first book came out in 1973, making 2023 your fiftieth year publishing poetry books. Despite all those years, it feels like you’re speeding up your rate of production—three poetry books in the past five years! To what do you attribute this acceleration?

When something huge is bearing down on you, your instinct is to step out of the way. When that option isn’t available, then you speed up and hope to avoid a little longer that cataclysmic meeting. Perhaps that explains my acceleration. That and the fact that I am retired from outside work and hence I’m able to devote my time to two of the great loves of my life: reading and writing. I don’t have a television, I rarely watch movies, and so I find myself in the enviable state of being free to read and write. I think I have at least one more book in me, perhaps two, and I am sifting through my previous publications as well in attempting to compile a Selected. This I am doing with the help again of friends who have alerted me to look again at poems from the past that I might very well have dismissed or overlooked, my eye somehow always needing to be elsewhere.

A Selected! I can’t wait to read it. Have you sensed, in your sifting, that what you want from a poem, or a book of poems, has changed?

At the moment my poems are getting shorter, as if a new kind of lyricism has emerged as part of my late style. But of course one little shift and everything changes…

David Zieroth’s The Fly in Autumn (Harbour, 2009) won the Governor General’s Literary Award and was nominated for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize and the Acorn-Plantos Award for People’s Poetry in 2010. Zieroth also won The Dorothy Livesay Poetry Award for How I Joined Humanity at Last (Harbour, 1998). He watches urban life from his third-floor balcony in North Vancouver, BC, where he runs The Alfred Gustav Press and produces handmade poetry chapbooks twice per year.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸ was published by Biblioasis in 2021. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.