The following interview is part five of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

The City Lights of Sialkot

When it is dark enough

our whole family climbs to the rooftop

to witness the unaccustomed glow

creeping across the southern hemisphere

marking the miracle of electricity

inching towards our home

to forever blot out our familiar

and created stars

Abaji waves at it

and says one word

Sialkot

he holds my hand tight

whispering

soon soon

That is the moment

ammiji knows that her other child

will be a girl

and that she will name her

Roshni

Light

Somewhere in the distance

a steam locomotive sounds its whistle

the wave travelling ten miles

over unharvested fields

before striking our home

Reprinted with permission from Exit Wounds (Caitlin Press, 2022)

Rob Taylor: Poems in Exit Wounds document your eviction from your house in Kuwait during the first Gulf War, and all you had to leave behind as you fled as a refugee (family videos, precious mementos, and, I assume, many a book). Could you talk a little about that experience?

TM: When I look back at the plight of South Asian immigrants who were, and still are, working in the Middle East, all I can recall is the bruised and precariat state we were all in and the daily professional and social humiliations that we endured. We were living in an apartheid state that categorizes its citizens according to their bloodlines and clan history (e.g. the existence of the Bedouins, who were the original inhabitants of the region, is only partially acknowledged). And, as non-Kuwaitis, as South Asians, we were at the penultimate bottom of the list. That final spot was occupied by people who had no country to return to and still do not, namely the Palestinians.

For us, the war further disrupted our already precarious lives, so we had to abandon all we had so diligently accumulated during our years in Kuwait. It also abruptly made all of us refugees.

As non-Kuwaitis, we were not permitted to own property, and our residences were always rented properties. Hence, I write in my poem “The Home Invaded”:

Though lived in for two decades

my rented Kuwaiti home I never dreamt you

even when locked out and distant to me

only desiccated houseplants beckoned

return

Christopher Levenson, who wrote the introduction to Exit Wounds, positions your books as a rarity: a Canadian poetry collection by a male South Asian poet (and, even rarer, one which focuses on South Asian history and literature). Was this something you were conscious of when writing the poems in Exit Wounds?

My conscious struggle as a writer has always been for an original voice that would illuminate a lived experience in a personal and relatable manner. From my close readings of paleo-anthropologist Loren Eiseley’s work, I have learned that to communicate a compelling experience or a resonant historical event, you must first relate it to your own lived history and experience; subsequently, I am always searching for that social or historical simulacrum that runs parallel to my life and which I can harness for my expression.

At later stages of the manuscript I even abandoned punctuation and grammar, a technique that I find fellow poet Tolu Oloruntoba has mastered by exhorting writers to “risk clarity.”

I characterized this process in a poem that tentatively begins: “all writers are flat-earthers in racing to the end of the line, and then reluctant to leap off the page, turn back to the safety of the next line—until they encounter the bottom of the page—and here they must take a leap of faith that a fresh page will allow them a landing…”

I write about borders, alienation, and expulsion, and all these states are realized as the domain of barbed wires and no-man lands where, as in my poem “Raising Nineveh,”

The wells are poisoned

The fields salted

You cannot stay here

You are not the first

to pass this way

Nor the last

2022 marked the 75th anniversary of the Indian Partition, and your book, in many ways, exists as a response to that event and its ramifications. How do you think the effects of the Partition changed the course of your life? What do you think you’d be writing about if it hadn’t happened, if you were writing at all?

Growing up in a border town, the impact of the British Partition of India in 1947 was impossible to ignore. The spillover from that brutality was all around us, in the traumas of our neighbors, in the defaced buildings of our neighborhoods, including our own street where I stumbled on a painted over pre-Partition mural. This early exposure to the brutalities of recent times past, and then the personal trauma of leaving Kotli for an English boarding school, were the best education I could have had. So, even if the Partition hadn’t happened, I would still be engaged with similar landscapes of human experience and historical trauma.

I have learned that to communicate a compelling experience or a resonant historical event, you must first relate it to your own lived history and experience.

Yes, I’d love to talk about that mural. In your poem “1954,” a boy repeatedly throwing a ball against a wall reveals a pre-Partition mural of Krishna that had been whitewashed over. When he tells adults about it, he is rebuked and the mural is quickly covered over. In writing frankly about difficult events such as the Partition, the Komagata Maru incident, 9/11, Indigenous residential schools, the killing of Robert Dziekański, do you sometimes feel like that boy, your words pushed aside and covered over? Or have people been more respectful and open in response to your poems?

I am glad my work is finding a home with its intended listeners and readers. And their emotional response and intellectual engagement show that I have conveyed something ineffable and essential with which they could identify. One of my roles as a writer/artist/curator is publicizing social and historical injustices. Fortunately, having lived so close to the barbed wire of police states for so long, I can continue to openly bring forth these topics in compelling ways.

The second section of poems in Exit Wounds, entitled “The Lives of the Poets,” includes tributes to many historical South Asian poets, including Rabindranath Tagore, Waris Shah, Mirza Ghalib and Faiz Ahmad Faiz. These poems are also larger celebrations of poetry, and especially the role poetry can play in South Asian communities. How would you describe the role of poetry in South Asia? How does it differ from its role here in Canada?

When I speak of these South Asian poets, I refer to them as emotional touchstones that continue to inspire me. The emotional resonance of their work draws you in and leads you to engage with their work more intellectually. Faiz’s creative expression continues to astound when he begins with lyrical romanticism, and then the closer you read his work, the more you realize the subliminal intellectual level layered beneath it. I am increasingly frustrated by how few western readers are aware of the caliber of his oeuvre. However, his energized and devastating use of the words azadi (freedom) and bol (speak) are now gathering resonance and traction internationally.

My choice of these poets was also based on the tangential relevance of their work to the struggle for independence from colonization in general and to the Partition in particular.

In addition to considering historical South Asian poets, in your acknowledgements you also recognize modern Canadian poets of South Asian origin, including Kuldip Gill, Sadhu Binning and Ajmer Rodhe. Could you talk a little about all of these influences—historical and modern—and how they’ve worked together to shape your writing?

The influence of Sadhu Binning and Ajmer Rodhe has been critical to my creative output. Through reading their work, and my subsequent discussions with them, I re-imagined the local historical events of 1908-1914, especially the circumstances surrounding the Komagata Maru and its impact on the South Asian community in Canada. I have credited them both as my teachers in my last two books. And Kuldip Gill’s poetry is an endless wellspring of inspiration for me.

It was a struggle pinning the words to the pages. Often, all I wanted to do was violently break open the language to express my own rage.

In Levenson’s introduction, he writes that “one senses a strong oral tradition” in your poems. You close your own forward to the book with an encouragement for the reader to “stand up and speak these words aloud—poetry must not be read in the dark or silently.” Do you write your poems for public performance, and as such do you think of them as performance poems or “page” poems? Or is that distinction even relevant to you? Was it a struggle pinning your poems down to the page?

I create work that is meant to be performed and not merely read. For instance, when I wrote the very brief poem “EntryExit Wounds,” I imagined the reader standing before an audience and hurling each insult (eight pejoratives for “immigrant,” taken from eight different cultures) as stones. In fact, when I read it aloud, I hurl each term at the audience physically like a stone. Once in a while, someone in the audience will flinch reflexively. At the conclusion, I flip the common insult “go home” and toss it back at the attackers.

EntryExit Wounds

(In memoriam – Chin Banerjee 1940-2020)

Jis tara bund darvazoN pe gir-e bearish-e-sung—Faiz

MOHAJIR

PANAGHIR

RAFIQ

PAKI

IMMIGRANT

REFUGEE

WETBACK

FOTB

It is midnight already

tell those

who hurl stones at my windowpanes

heed your words

Go home

The poems in Exit Wounds flow very naturally despite a lack of punctuation (so naturally that I didn’t notice this fact until near the end of my first reading). Could you talk about your approach to line breaks and spacing, and how they recreate the pauses in natural speech?

It was a struggle pinning the words to the pages. Often, all I wanted to do was violently break open the language to express my own rage. Hence, each poem follows a different flight to its volta. Imagine a work that has no capitalized letters. Then you encounter the tyranny of a capital “I.” Besides, the small “i” conveys volumes. This technique is further illustrated in my poem “Midnight on Turtle Island,” where beyond the issues of capitalized words, the narrative that takes place during the night is set in a black background, and with the end of the “Century of the Night” reverts back to black text on white. Incidentally, here all pronouns are now capitalized. “Midnight on Turtle Island” also raises several challenges for the physical reading of the poem as it presents three different narratives in three distinct voices without any assignment of speakers.

We first met at an event hosted by the New Westminster (now Vancouver) reading series, Poet’s Corner. That series means enough to you that you mention it in your author bio. Could you talk about the importance of Poet’s Corner in your development as a poet, and your sense of belonging within a poetry community?

Poet’s Corner performs a vital role in the development of poetry locally by offering up fresh voices monthly and allowing developing poets valuable exposure and a receptive audience.

I would like to offer parts of this poem in concluding my take on the role of the Poet’s Corner:

This is what I know of safe haven

this is what I believe

this is how I celebrate

here and now

Hammering out stars

into the smithies of the night

Each oscillating shining orb

held up before your eyes

tilted just so

Where confident as dancers leaning into curves

we skate unabashedly into our swagger

so close to the edge

immaculate in our poise

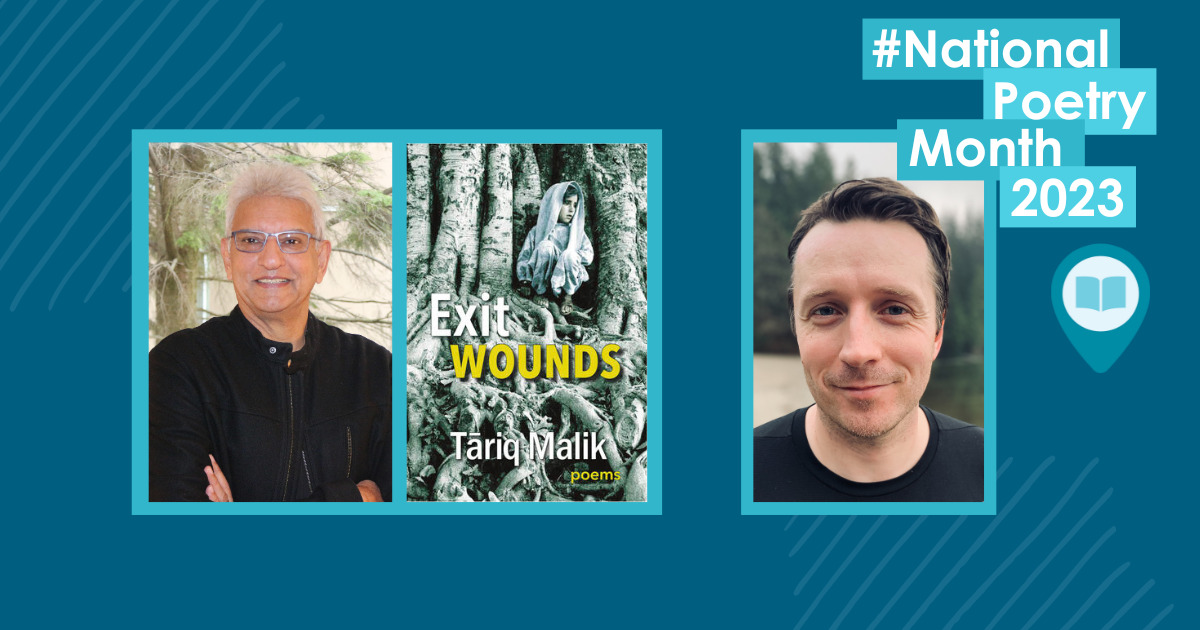

Tāriq Malik works across poetry, fiction, and art to distill immersive, compelling, and original narratives. His working English is a borrowed tongue inflected with his inherited Punjabi, Urdu, and Hindi languages. He writes intensely in response to the world in flux around him and from his place in its shadows. He came reluctantly late to these shores, having had to first survive three wars, two migrations, and two decades of slaving in the Kuwaiti desert. Tāriq Malik is the author of a short story collection, Rainsongs of Kotli, and a novel, Chanting Denied Shores. His debut poetry collection, Exit Wounds, was published by Caitlin Press in 2022.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers, was published by Biblioasis in 2021. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.