The following interview is part two of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Ballad of the Pea and the Shell

Le Testament (67-69)

Once deceived, I came to see how one

object may be exchanged for another –

a gong goozler for a digit

an email for a bum itch

a Kriegspiel for a sailor

a foot long for a banana stick

– & how cheats use slights & devices

to swap verse & vice versa –

a shanker for a charnel house

a deck of cards for a dolly spot

a tavern for a Tappecoue

a sticky bag for a skeleton

– which is how Love deceives & leaves

us banging on the Prison House door.

Reprinted with permission from After Villon (New Star Books, 2022)

Rob Taylor: François Villon was, to say the least, a character. A criminal and a cheat. Both his poems and life story are filled with misdirection, subterfuge, and gaps. In the acknowledgments to After Villon, you write that you began translating Villon shortly after first encountering his work in 2009. What was it about Villon that drew you in so quickly and so fully?

Roger Farr: It was precisely those things you mention. That and the fact that Villon, a medieval poet, was the first to erase the separation between his art and his life, which arguably makes him the first avant-garde writer. But for some time before I read Villon, I had been interested in political and aesthetic discussions about visibility, readability, and clandestinity, topics I wrote about for anarchist publications. When I was working on a piece for Fifth Estate about the work of the Situationist Alice Becker-Ho, who introduced me to Villon, I learned about his poetic use of coded language, deceit, and slang, and I became deeply intrigued.

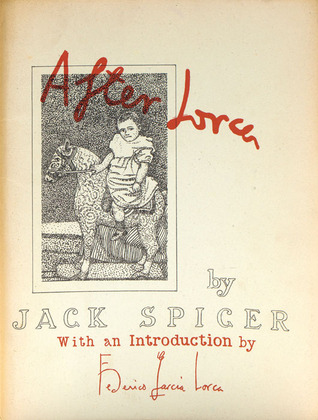

Villon’s influence on After Villon is obvious, but as I read your book I started to think of the title as being composed of two parts, with the “After” actually pointing to Jack Spicer, whose After Lorca—with its loose translations and “correspondences” from Spicer to Lorca—served as a template of sorts for your book. Did you ever feel tension in trying to honour all three “contributors” (Villon, Spicer, you) in one book? If so, how did you manage that?

As soon as I started to see my accumulating translations as a book, I knew I would use After Lorca as a template. I have always found Spicer’s poetics difficult to comprehend, which is no doubt part of my attraction to his work. But I thought the correspondences he writes to Lorca were a brilliant way to elaborate a poetics of translation without resorting to overly expository prose. So he was mostly a formal influence, at the level of the book. Ultimately, my eyes and ears were always attuned to Villon.

Villon, a medieval poet, was the first to erase the separation between his art and his life, which arguably makes him the first avant-garde writer.

In your first “correspondence” with Villon, you note that you “cheat” in your translations, in part in honour of Villon’s own manipulations of the truth. One such “cheat” involves frequently zipping Villon from the French middle ages to twenty-first century coastal British Columbia (one poem opens with biographical details of Villon’s life and closes with mentions of “homeslices,” “toonies,” and Abbostford’s Matsqui prison).

The book opens with an epigraph from After Lorca, “Objects, words must be led across time not preserved against it,” which seems to be speaking, at least in part, to this maneuvering. Could you talk about the Spicer quote and your choice to lead Villon “across time”?

Spicer’s idea of words as objects points to the materiality of language. When I was translating Villon, I experienced this materiality as a profound opacity and “thickness.” Villon was, of course, writing in Middle French, which, like Middle English, I have no grasp of whatsoever. To make matters worse, it’s not always clear when he is using a coded language designed specifically to shut out police and other “hostile informants.” For example, every word attached to the concept of “marriage” potentially refers to being executed: a “bridegroom” is someone who is going to be hanged (this particular example resonated for me on a number of levels). So when I was “leading the words across time,” I was in many cases trying to translate the opacity, rather than the denotative or even connotative meanings of words as such. An indirect or possible reference to prison, then, might turn up in my poem as “Matsqui.” Instead of trying to “preserve” a literal meaning, I would activate a more recognizable “object”.

Your book’s jacket copy notes that your translation “refuses the heteronormative assumptions all too often applied to the “gaps” in meaning of the original texts.” Would you consider this another of your “cheats,” or a correction of an inaccurate record? Was it something you planned on doing from the beginning of the project, or did it happen more gradually as you worked through the poems line by line?

I would say “correction of an inaccurate record,” and yes, something that happened gradually. The more deeply I read Le Testament, the more the ambiguities around Villon’s sexuality stared back at me. This was undoubtedly linked to my own life and experiences during the period I was working on the book.

But there is also some textual evidence that Villon was queer, or at least “not straight.” Villon’s insinuations that certain police were soliciting young male sex workers, along with his intimate knowledge of where to find them, seemed worth pausing on. There is also what has been called his “trans ventriloquism,” which refers to the manner in which he suddenly speaks as a woman. In one of his most famous Ballads, which I translate—and am quite proud of—he writes from the perspective of an aging female sex worker recalling a bad trick.

This fluidity in his work was emphasized by Thierry Martin, who published a remarkable and controversial translation of Villon from Middle to Modern French, called Ballades en Argot Homosexuel (“Ballads in Homosexual Slang”). Martin was working with the three-part “queer code” identified by linguist Pierre Guiraud, which holds that every line in the Ballads in Jargon can be read three ways at once: as a warning not to get caught cheating at cards, as a warning not to get busted by the authorities, and as a warning not be outed as queer. I found this fascinating, and it strongly influenced how I read the poems.

Even where sound and sense are separated, those rhetorical features and the poem’s overall “hum” remain intact.

How did your choice to embrace the fluidity in his work change the way you thought about Villon’s poetry?

There was a distinct shift in my “orientation,” in terms of both language and identity. As Foucault has taught us, the categories of “heterosexual” and “homosexual” didn’t exist in the Middle Ages. Villon’s sexuality was therefore a cipher to me, as opaque as his language. In fact, the entire notion of orientation—especially the idea of a stable identity induced from a sexual inclination defined by the gender of one’s partner(s)—seemed increasingly odd, in literature and in everyday life. Eventually I came to experience poetry and desire on a more somatic level, as forces that work to unbind (to use a term from Freud) identity, language, and “orientation.”

How did that shift in orientation shift the translations themselves?

While I didn’t follow Guiraud’s and Martin’s approach exactly, my project shared their desire to “make Villon queer again,” if I can put it that way. To accomplish this, I was guided by Marc Démont’s thesis, in his essay “Three Modes of Translating Queer Literary Texts,” that queer translation “focuses on acknowledging [the original’s] disruptive force and re-creating it in the target language.” This is accomplished by critiquing existing translations, and then developing new linguistic techniques designed “to re-create in the target language the queerness of a text.” The queer translation subverts gender stability and maintains the source text’s “thickness” and opacity, rather than domesticating or normalizing it. That’s what I was after.

Translating poetry from another language is challenging enough, but Villon’s work adds the aforementioned challenges of his various “opacities,” most notably his use of thieves’ jargon and words of his own devising. Did you find that complicated your work as a translator, or did it in some way liberate you, knowing that an “accurate” translation was likely impossible?

Yes and yes! At times I imagined what I was doing as a kind of psychoanalysis—deciphering exquisitely complicated “defense mechanisms” designed to throw me off the case. But the realization that I would never “get it right” was very liberating. I let go of any desire to “master” poetic language a long time ago, and instead learned to enjoy the free play and signification of words. It’s something I notice a lot of my writing students struggle with. For me, difficulty and complexity are an invitation into collaboration and creative problem solving. As a writer I thrive there.

Whenever I read a book in translation, I want to place it beside other translations of the same text to get a sense of this particular translator’s style. This was perhaps doubly true of Villon, as the “creative problem solving” involved could take various translators in very different directions.

You’ve generously provided readers with just such a comparison: in “Compario,” you present nine translations of a Villon quatrain (including a “Dictation” version, which delightfully translates “Dont maintz marchans furent attains” as “Don’t mate Marshawn’s friend okay”). Why was it important to you to include that sampling from other translators?

In “Compario,” I wanted to make my methodology visible. This always involved flipping between the original, several dictionaries, and multiple translations into both English and Modern French. When I was really stumped and felt like I was going to fold, I would use dictation software to kind of “blast” something new out of the source text, and then work with that. I refer to this as “bluffing.” It was a lot of fun. I am aware this would be regarded as complete and utter blasphemy for many translators, but I agree with Nathan Brown, who in his introduction to his masterful new translation of Baudelaire’s Fleur de Mal, suggests that a translator may take creative liberties when confronted with impossibility. Granted, I take more than a few such liberties, which is an index to the degrees of impossibility I encountered. In some cases, I had no choice but to insert poems Villon hadn’t actually written. Lorca accused Spicer of this, too.

For me, difficulty and complexity are an invitation into collaboration and creative problem solving. As a writer I thrive there.

Speaking of Spicer, in one of his letters to Lorca he writes that, “The perfect poem has an infinitely small vocabulary.” What would you say to that?

That’s one of those provocatively cryptic utterances Spicer is so good at. I think he is referring to the poetics of les mots justes, which requires precision and economy in language, plain speech, and a generally minimalist formal aesthetic. I am slanted more towards poetic maximalism these days—excess, clutter, chaos, colour, noise, etc.

What do you think Villon would have said to Spicer?

Interesting. I’m not sure Villon’s work is compatible with the idea of the “infinitely small.” He wrote in popular forms and was very much a poet of the streets and the taverns, albeit a highly educated one. His language is full of excess: carnivalesque, ironic, idiomatic, mocking, oscillating between high and low genres. It was also, for tactical reasons, lexically dense and expansive.

Let’s add a couple more poets into the discussion: in an essay on his loose translations of Rilke, Don Paterson said, “If we are not prepared to make a choice between honouring the word or the spirit, we are likely to come away with nothing.”

I’m not sure I understand what is meant by “spirit” in Paterson’s statement. Is he referring to the aporia between signifier/sound and signified/sense, perhaps?

Yes, I think so. At the level of the word, and also the poem—the spirit of the whole piece.

It’s a constant question for a translator. In my case, I was confronted with signs (sounds) that had no “sense” or “spirit” or “signification;” or if they did, they were literally being deployed as screens to lead interpreters (translators!) away from their referents.

Villon haunts everything I write now, and remains my poetic Master.

When I offered the Paterson quote to Steven Heighton, who called his own translations “versions,” he replied in a way that suggested a choice between word and spirit might be impossible:

“In poetry there’s no Cartesian separation of mind and body or content and form… The poem is its music. Poetry is a form of song in which the words are obliged to create their own rhythmic and musical accompaniment. So, as a translator, you have to try to approximate the poem’s rhythms and, if I can put it this way, melodies. And, if the original is rhymed, well, that’s part of its essence and you need to try to reenact it somehow in your translation.”

I felt in reading your translations, and your correspondences about them to Villon, that you might both agree and disagree with both Heighton and Paterson…

Yes. I might disagree with Heighton’s idea of rhyme as an “essence.” I think demands of syntax and tone, rhetorical and literary devices, etc. can and should sometimes trump the element of rhyme. We’ve all read translations where fidelity to rhyme leads to some pretty clunky language. But I like what he says about trying to “reenact” it, which perhaps points to some other possibility for how we conceive of rhyme. For me, rhyme is simply the patterns of repetition that hold a poem together; they establish its rhythm. This includes repeated vowel/consonant combinations like “home” and “tome,” of course, but also repeated syntactical constructions: for example, ending each stanza with a question, or uttering a warning every few lines. These are also repeated elements and should “count” as rhyme.

In After Villon, I sometimes tried to keep conventional rhyme operating (both end-stopped and internal), and in some places I maintain a “fidelity” to the original poems (despite the consistent mocking of marriage and monogamy). But I was generally more interested in translating things like addressivity, the conspiratorial tone, the pleading for mercy, the warnings, etc. Even where sound and sense are separated, those rhetorical features and the poem’s overall “hum” remain intact. At least that is my hope.

I love that idea of a poem’s “hum.” I think Heighton and Paterson would like it, too.

In After Lorca, Spicer writes “Loneliness is necessary for pure poetry,” and it strikes me that exile is a part of both Villon’s story (banished from Paris in 1462) and your own, far more voluntary, “exile” from Vancouver to Gabriola Island.

Of the bar-hopping social life common to both Spicer and Villon, you write “I am far away from that now & have been for many years.” Did you sense a parallel between the change in Villon’s life and your own?

I was part of a rigorous literary bar scene in Vancouver for some time. And I’m not entirely sure if my departing flight from the city in 2004 was with Exile or Banishment. As with Villon’s exit from Paris, I am certain a few people were relieved to see me go. The feeling is mutual. There are some remarkably petty people in the writing scene I once belonged to. I address them in a few places in the book. They seem to find their agency in gossip and rumour. They can be hard to spot, because they only emerge from their holes when there is a little piece of cheese waiting for them. But they know who they are.

Ha! While we know your post-banishment fate, no one knows what happened to Villon—he simply disappeared from history. Were you in some way translating Villon from a place beyond his known history; from that next, quieter, space his life may have entered had he lived long enough?

Rabelais suggests, in an obscure passage in Gargantua and Pantagruel, that a few years after his banishment, Villon emerged in a theatre troupe in a remote village, and lived out his life there quietly and happily. I think that is unlikely, given Villon’s temperament and criminal associations and Rabelais’ tendency to satire and invention. I suspect Villon met his end on the gibbet, in a dungeon, or in a brawl. I hope my fate is more along the lines of what Rabelais imagined.

Yes, sign up for that theatre troupe, already! On the subject of endings, near the close of the book you write of being done with Villon (“For me you are an ancient city bombed…”). This mirrors Spicer’s eventual shrugging off of Lorca. Did you really feel done with him? And did that tiring of him go deeper than normal end-of-book fatigue?

Mostly that was in keeping with the trajectory of Spicer’s “break up” with Lorca. When the book finally went into production, though, I carefully removed all the translations and dictionaries and critical studies from my desk and put them on a shelf in a bookcase in my bedroom, then replaced them with the books I will be using for my next writing project (a collection of essays and translations on anarchism and sexuality). I worked on my slim book of Villon translations on and off for ten years, so I was glad to move on to something else. That said, Villon haunts everything I write now, and remains my poetic Master.

Roger Farr is the author of five books of poetry: Surplus (2006), Means (2012), IKMQ (2012), a finalist for the BC Book Prize in Poetry in 2013, I Am a City Still But Soon I Shan’t Be (2019), and most recently, After Villon (2022). The Amorous Comrade, a collection of essays on anarchism and sexual politics, is forthcoming in 2024.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers, was published by Biblioasis in 2021. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.