The following interview is part seven of an eight-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. The series will run from January until the end of April, National Poetry Month. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018).

Rob is also an instructor in Creative Writing at Simon Fraser University Continuing Studies.

my father is dying – Krys Yuan

my father is dying and i’m still going to the beach

lying my back across the grassy sand

resting my eyes against the glare of the sun

pulling my feet towards the ocean between us

imagining that pain irradiating one half of my dna

my father is dying and i’m still going to the grocery store

i line my grocery cart with knowledge of produce that he’s

given me:

extra fish eyes means bright eyes

black rice vinegar eases any stomach

rock sugar lilts our mother tongues

my father is dying and i’m still going to be writing

how ridiculous is it that his body eats his dreams

shrinking the edges of his world

composting his future

while my body eats away, ballooning,

blossoming

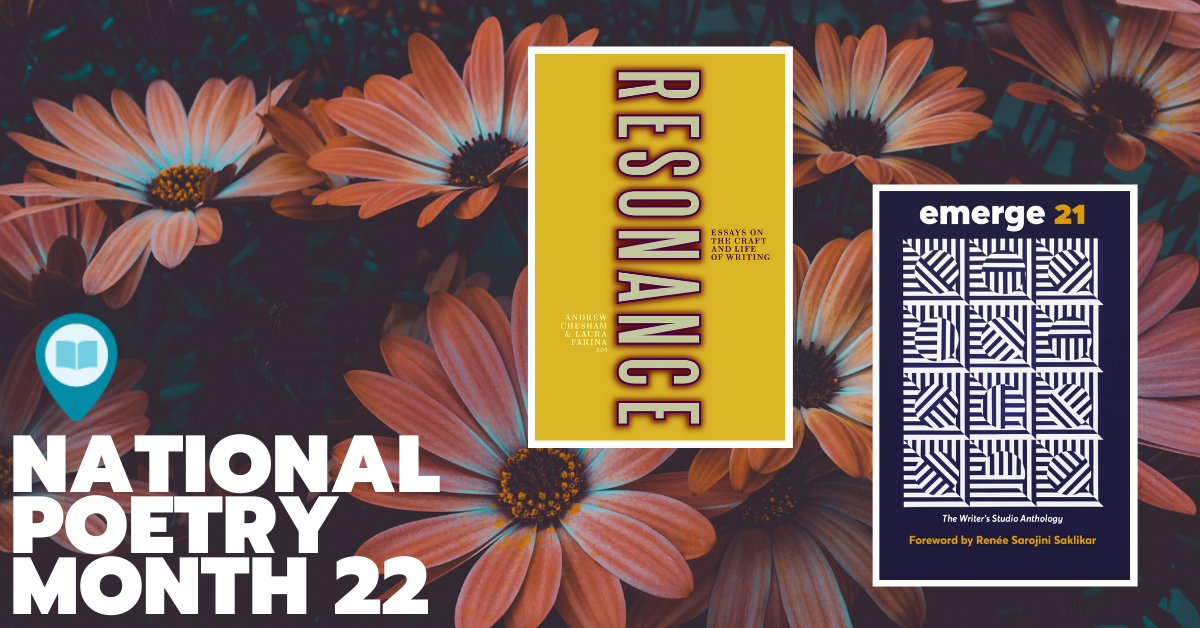

Reprinted with permission from emerge 21: The Writer’s Studio Anthology (SFU Publications, 2022).

Rob Taylor: Normally in this series I interview a poet about their new poetry collection. In this case I’m interviewing two writers about two anthologies, all at once. Could you tell us briefly about your roles at SFU’s Writer’s Studio program, and the two TWS-affiliated books you’ve put out, emerge 21 and Resonance: Essays on the Craft and Life of Writing?

Laura Farina: We’re the administrators behind The Writer’s Studio, SFU’s year-long creative writing certificate program. In our day jobs this can mean anything from planning programs, courses and community activities, to helping individual students and instructors with specific problems.

Every year, the students in The Writer’s Studio collaborate on publishing an anthology called emerge. In that process, I act as publisher, and we bring back alumni from the program to act as editors. Students submit their work for publication, and also volunteer as members of the production and editorial team.

Andrew Chesham: The idea for Resonance came as we were approaching the 20th cohort of The Writer’s Studio and were looking for ways to celebrate. We kept coming back to this idea of all the conversations that have happened in and around the program over those twenty years. It’s our favourite part of our jobs, getting to talk about writing with other practicing writers. We wanted to capture that in some way, to invite anyone who was interested into our writing community. I think as writers, it’s really comforting to know that we all struggle with the same things. We’re all trying to solve the same kinds of problems.

RT: I love the choice to widen the circle of those conversations to include aspiring writers outside your program. In addition to pulling the book together, you both wrote essays for Resonance: Andrew’s is about how maintaining a pre-writing journal can help you write productively every day, while Laura writes in her opening paragraph, “There are no techniques I use all the time. I don’t write every day. I use a notebook, but only sometimes.”

I cracked up reading that — it felt like the anthology was being edited by The Odd Couple (perhaps all co-productions between a poet and a novelist feel that way!). Did you find your predilections clashed or complimented each other in bringing Resonance together?

AC: Yes to both. I think the most valuable thing about editing this anthology together was having each other as a sounding board as we were working through the essays.

LF: We work in different genres (I write most poetry, and Andrew writes mostly fiction) and come at writing in such different ways, so if an essay felt like it was offering a valuable perspective to both of us, it was probably really onto something.

AC: It was illuminating in terms of process, too. I think we learned a lot about each other and the ways we both work. I tend to approach writing in terms of “Let’s bang it out and then do it again, bang it out and do it again.”

LF: Andrew’s favourite phrase is “Big picture…” and I tend to revise more as I go. My approach is, if you can get a key sentence perfect, you can build out from there. So Andrew’s edits would be like, ”I think we should ask for the following sweeping changes, and I’d be like…yes, and also, can you ask them about what’s up with the comma in the first sentence of the last paragraph?” I may be exaggerating a little bit, but that’s how it felt, anyway.

I think as writers, it’s really comforting to know that we all struggle with the same things. We’re all trying to solve the same kinds of problems.

RT: Poets, am I right? What was the hardest part of the collaboration?

AC: Writing the introduction.

LF: And I think that was the most fascinating, too. Because Andrew’s goal when he’s in the thick of a project is to write every day, which means he writes through tough days, and the thing he wants most from a book like ours is the feeling that he isn’t alone in the struggle, that others have tackled what he’s tackling and come through the other side. I’m maybe more of a fair weather writer, and when things get too tough, I tend to go watch TV. This means it takes me a hundred years to finish anything, but also I’m always looking for ways to shake up my writing process and make it fun and enticing. Trying to cram both of those positions into one introduction required some serious negotiation.

RT: This sounds a bit like what former TWS director Wayde Compton would call a “rupture”: in his essay in Resonance, Compton writes about that moment in a writing project where the author’s initial plans fall apart and they have to re-envision their book. He writes that this rupture can be difficult to accept, but that “what feels like the failure of a project is, in disguise, the chance to make it better, if you’re willing to adapt and listen.”

This seems like a valuable lesson for both writers and anthologists, perhaps especially anthologists, who in many ways have less control over the final product. Introduction aside, I’m curious if, in pulling together Resonance, you experienced a rupture which required you to adapt and listen? How does the finished book differ from your initial vision?

AC: When we first conceived of Resonance, we thought it would be an anthology of short essays on craft. We thought each essay would be something along the lines of “This is a problem I’ve encountered and this is how I solved it.” In this way, I think we were anticipating essays that all had a similar approach and tone.

LF: One of the first essays we received was by Andrew Steeves. It’s called “Notes on Publishing Literary Books” and it’s a list of all his thoughts and feelings about why he publishes in the first place and why he publishes what he publishes, so not at all what we were picturing. And it was good. So, so good. We had two choices. We could either send back an awesome essay and ask for extensive revisions or we could expand our idea of the anthology to let in more perspectives. Did we even talk about it? I can’t remember.

AC: I don’t think we did. The essay was that good.

LF: As the essays came in we found more and more people were writing about their lives as writers, trying to weave together all these disparate threads to explain how they create what they create.

AC: I think the finished anthology is a lot more honest about all of the different elements that go into writing a piece. When we conceived of this anthology we were thinking about the writing process in a simplistic way. No challenge that exists in a piece of writing exists on its own. For example, you might identify that the dialogue in something you’ve written feels stilted. Okay, but why is that? Maybe you don’t know your characters well enough. Maybe you haven’t compressed time effectively. Maybe this section of your writing project is just kind of boring for you. Most likely it’s a little bit of all three.

No challenge that exists in a piece of writing exists on its own.

RT: Oh good, I was hoping we could talk about Steeves’ essay, which is one of my favourites in the book. I especially appreciated your including it as it’s critical of Creative Writing programs, and it’s not the only one in the book (George Bowering: “When we were published tyros, / those professors and old anthologized poets // said we had to work long / to become masters. // The first / intelligent thing we said back / was that poetry / didn’t want masters”).

In his essay, Steeves’ writes that “the Creative Writing Industrial Complex appears to dull many more blades than it sharpens” and that, instead of promoting originality, writing programs “seem more successful at fostering uniformity.” The idea that creative writing programs risk dulling originality is a fairly common one — do you think there’s some truth to it? In your program, how do you work to avoid “fostering uniformity”?

LF: I think the first thing anyone who wants to write knows how to do is to mimic the writing they admire. And you know, we’re all human, we all like praise. So you get a room full of people who want praise and are good mimics, and if you’re not careful, new writers start to write specifically to impress the people in the room. And this, I think, is what Andrew Steeves is talking about when he refers to uniformity. I think the main thing we do in The Writer’s Studio to avoid this is that our mentors select their workshop groups from all the applications that we get. This means that mentors are genuinely excited by the writing their workshop students are engaged in. So hopefully that means they want to encourage that writing to be more itself, rather than squishing it into some kind of “good writing” mould.

AC: One of the things we’re always trying to do is meet our student where they’re at. Writers come to our program from such different places and spaces, it would be hard, I think, to get them to all sound alike.

RT: Steeves’ essay comes at the end of the book, where it’s joined by three others written by Canadian small press publishers. I love that you included publishers’ voices in there! Some writing classes/programs seem to believe the business side of the industry is outside the scope of their purview, while TWS always seems to have one eye firmly on the end-goal of publication. But the risk in emphasizing publication is that it can lead to writers truncating their creative exploration in their rush to the finish line. How do you balance the need for play and experimentation in a writing program with the desire to create a finished product?

LF: First of all, there’s nothing wrong with never publishing what you write. If there’s one thing that I want people to take away from this book, it’s that writing is enjoyable in and of itself. It’s a good way to pass an afternoon. The problem, I think, is that sometimes not wanting to publish is a knee-jerk reaction to not wanting to be rejected. Which is valid, because the only way to not have your writing rejected is to never attempt to get it published (I may have just talked myself out of all my future publishing dreams here).

Publishing is a tool, and just like understanding story structure, or being able to use setting in interesting ways, when you understand the tool you can use it. Having publishing as an end goal can help you finish work. It can also help you feel like your work has a larger purpose in that others might read and connect with it. In both our book and our program, we talk about publishing because then it’s out there as a possibility, and it stops being this big moment of like, when this happens for you, you will officially be A Writer. Which, you know… just isn’t true. You don’t need to use the tool the moment you learn about it. You can put it away until it makes sense for you. One of the beautiful messages that comes out of the essays by publishers in Resonance is something along the lines of “Write the thing you want to write, the thing that only you can write. Make it as good as you can. There are people who are going to want to read that. We’re here when you’re ready.”

AC: We wanted to include publishers in Resonance to humanize them. People often put publishers on a pedestal, but they’re just people with their own interests and tastes. We wanted to add their voices so that writers could get a sense of how a publisher selects and makes their books.

One of the beautiful messages that comes out of the essays by publishers in Resonance is something along the lines of “Write the thing you want to write, the thing that only you can write. Make it as good as you can. There are people who are going to want to read that. We’re here when you’re ready.”

RT: emerge seems like a part of this demystification process, too, giving new writers like Krys Yuan (whose poem opened this interview) an in-program glimpse into the world of publishing.

LF: The first time you publish your work is going to be messy — full of hand-holding, freaking out, and being weirdly paralyzed about writing your own bio. emerge gives writers a chance to get that out of the way in the company of friends and mentors.

RT: In her foreword to emerge 21, Renee Sarojini Saklikar writes that one of the great benefits of the program is coming “to know thyself as a writer,” which involves “knowing what supports your “habit” of writing and knowing what can erode that daily commitment.” I like the balance Saklikar presents here between cosmic concerns about one’s life as a writer, and micro-concerns around the day-to-day realities of the “habit.”

Similarly, Resonance is subtitled “Essays On the Life and Craft of Writing,” with essays whose subject matter runs the gamut from grammar and revision; to public speaking and breath; to race, counseling and even baseball (that last one’s George Bowering’s, of course). Could you talk about this balance you’re aiming for, both at TWS and in the books you publish, between lessons on life and craft?

LF: I think the main thing I learned in editing this book is that the “life” of writing and the “craft” of writing are profoundly interconnected in a way that is at once cosmic and intensely practical. For a long time, I’ve felt that I’m in this whole writing business for the days when writing comes easily and it feels like you’re rolling down a hill and also your brain is on fire. Do you know the feeling I’m talking about? All of a sudden you’re finding all these connections and you have a moment of “OH! That’ what I’ve thought about this thing the whole time!”

Editing this book made me think more about the ways that you can lay the groundwork for cosmic moments by asking yourself questions about point-of-view, or proximity, or associations, for example. It made me understand that being able to recognize when there’s something profound happening within your piece, and being able to write your way deeper into it, is really all we mean by craft. Also, by taking a walk you can make sure you’re not feeling listless when cosmic inspiration strikes. That’s super practical advice.

RT: You may have just answered this with the walking tip, Laura, but I’m curious if there’s one lesson from an essay in Resonance that you think about now in your own writing practice?

AC: There are lots of pieces in Resonance I take comfort in. You’ve already mentioned Wayde’s piece about the rupture—that’s definitely one of them. Going into a project knowing that at some point it’s going to fail makes me worry about failure a lot less. Similarly, Reg Johanson’s essay about grammar, and the power dynamics inherent in standard grammar, felt very freeing to me.

LF: I keep coming back to Raoul Fernandes’ essay “Birds Outside the Boardroom Windows.” It captures my own poem-making so accurately that it gives me goosebumps.

. . . being able to recognize when there’s something profound happening within your piece, and being able to write your way deeper into it, is really all we mean by craft.

RT: Most of the essays in Resonance are followed by a writing exercise. Why was this important to you in thinking about the book and how you hope for it to be used by readers?

LF: In the end, you’re going to have to write.

AC: Despite the fact that there are a number of essays in this book that touch on the idea that you can be “writing” when you aren’t physically at your desk writing, I do think there can be a tendency to use these sorts of books as a way to avoid the hard work of actually writing. We wanted the essays to be relatively short, with each ending with an invitation to sit down and write, in the hopes that people would use this book as a way into writing, rather than as a way to procrastinate away from it.

LF: For a while, above my desk I had a note to myself that just read “Whatever you’re doing with those Post-It Notes is not writing”. There are so many delightful ways to procrastinate.

RT: Ahaha! I love that. Have you tried out any of the exercises? Does one stick out to you as your favourite?

AC: We’ve been working on this book for a while, so I’ve had the pleasure of using a number of them as I work my way through my writing project. Given where I’m at now, I’ve been using Claudia Casper’s exercise for mapping the chronological order of a story versus the narrative order of the story.

LF: I am really obsessed with Joanne Arnott’s “freewrite, choose words, arrange words, add bridging words” prompt. I’ve done it so many times since reading it in Resonance. It’s also a really wonderful way to collaborate with other writers. This weekend, I tried to do it with my 4-year-old. It’s possible that we wrote the world’s first poem that uses the words “poo poo butt” more than once.

RT: My son would respectfully challenge you on that point.

Andrew Chesham is the director of the Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University. He has worked in the literary arts since 2006, as a writer, editor, publisher, and educator in Canada and Australia. He has also edited the anthologies: From the Earth to the Table and Stories for a Long Summer (Catchfire Press).

Laura Farina is the author of two collections of poetry and a picture book. She has facilitated writing workshops in schools and community settings across Canada and the United States. She is currently the coordinator of The Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University.

Krys Yuan is an emerging theatre artist and writer, and a recent graduate of SFU’s Writer’s Studio. Born and raised in Singapore, she dances between her work as an actor, playwright, poet, writer, producer, among many things. Her writing practice is invested in alternate realities, speculative fiction, and investigating Asian diaspora alongside colonialism. In her free time, she dreams of being a cat parent.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸was published by Biblioasis in 2021.He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews at: http://roblucastaylor.com/interviews/