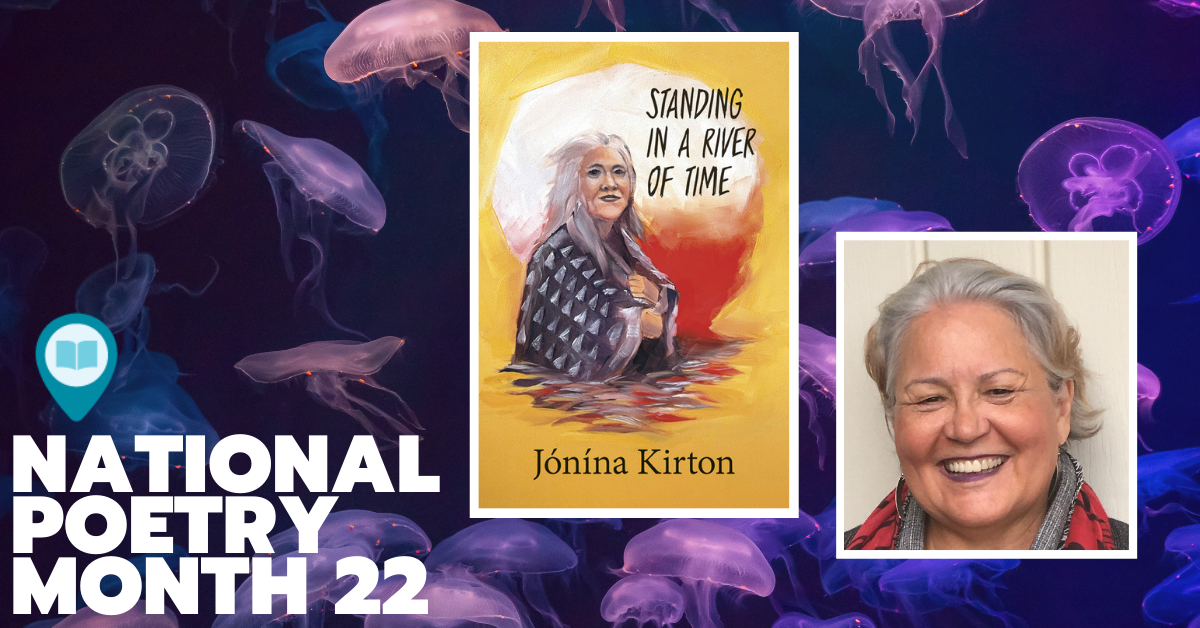

The following interview is part six of an eight-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. The series will run from January until the end of April, National Poetry Month. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018).

Rooted – Jónína Kirton

for my niece Gabby

I am rooted, but I flow.

—Virginia Woolf

The Waves (1931)

I am a story within the stories of many

I am a paradox

one thing and then another

parts of a whole

that does not know itself

turning towards the invisible

I can see the limits of knowledge

the places where formulas dissolve

into knowing that can only come

when quiet and walking in a forest

where the standing ones watch and wait

for us to return to ourselves

to the new stories that are waiting to unfold

Reprinted with permission from Standing in a River of Time (Talonbooks, 2022).

Rob Taylor: Standing in a River of Time is a hybrid — part prose memoir, part poetry. Each section opens with a prose narrative and closes with poems on the same subject. What drew you to this structure, as opposed to writing one or the other?

Jónína Kirton: This book was to be a collection of poetry. While working on the collection I had been experimenting with essay writing, and had a few essays published in anthologies. One of the essays is in Good Mom on Paper, and it includes a poem that is also in this collection. I found it hard to write about being a mother, and yet it was such a big part of my life. As with every other essay I had written I had many false starts. After a number of attempts an idea emerged: perhaps I could not only merge prose and poetry, but I could also keep the prose short. I give thanks to the editors Jen Sookfong Lee and Stacy May Fowles for allowing me to experiment and to include a poem.

RT: What role did the mentorship of Betsy Warland (she who mastered the form so fully they named a hybrid book prize after her!) play in helping you find this form?

JK: After writing the essay for Good Mom on Paper, I returned to writing my book and did what Betsy had taught me; I let the narrative lead. I never intended for the book to be this long but as I wrote the prose kept coming. Then while working with my substantive editor, Joanne Arnott, a rupture occurred, and the book exploded. Suddenly, I was going back into some of my childhood. The book became about the effects of colonization on one Métis family. Often, the discoveries revealed in the book were happening for me in real time.

In many ways the narrative chose the structure. The writing of it was at times healing and had a mystical feel to it. I would sit at the computer, and it poured out of me. Sometimes I would be crying so much that the front of my blouse was soaked but I could not stop to dry my eyes. I had to keep writing.

It was my husband who noticed after reading the prose he felt the poems, most of which he knew well, were made stronger by knowing the back story. When he said this, I knew I was on the right track.

RT: In Standing in a River of Time, you write about the difficulties of living “in-between” — being Métis (an in-between of its own), and also Icelandic; never quite light- or dark-skinned “enough” for different people. It struck me that this book, in its hybrid form, is a kind of enactment of that in-betweenness. (Where will it be shelved in bookstores? What awards will it be eligible for? Etc.) Has writing a hybrid form helped you come to deeper understanding of your own “hybrid” nature?

JK: Yes. It has also helped me claim this hybrid nature more fully. I had to let go of concerns like what shelf will it belong on and the fact that it may not be eligible for awards. It is the story of my life. I did not fit anywhere. I was always in the in-between so why not embrace it and make it more visible to the world?

I was always in the in-between so why not embrace it and make it more visible to the world?

RT: Yes! That’s the spirit! Standing in a River of Time opens with a long epigraph from your aforementioned mentor, Betsy Warland, about “the impossibility of telling the truth.” In it, Warland writes “I had assumed autobiography to be an inscribing of identity. Suspected it to be an inscribing of identity. It is quite the opposite.” Could you talk about your choice to open with that quote?

JK: Honesty and transparency are very important to me, and I wonder how the world could change if we had more of it. It is after all why they called it the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. There can be no reconciliation without truth. Through my relationship with my dad, I learned I couldn’t put my reconciliation, my healing, in his hands. I had to hang on to my “truth” while at the same time understanding it was impossible to know the whole truth. I had so many holes in my memory due to trauma, and adding to this there was so much disinformation about our Indigeneity. For a time, it all caused me to doubt my place in the Indigenous world. I needed to know where I belonged. I had been gathering our stories for years, but in some cases lacked historical context. Reading books like Rooster Town and The Northwest is Our Mother: The Story of Louis Riel’s People, The Métis Nation really helped me locate myself in the Indigenous world. As I learned more about Métis history and my family’s role in the unfolding of what took place on Turtle Island not only did my views about my family change, but I also began to feel more solidly Métis.

I chose Betsy’s quote as it is impossible to “tell the truth” as the truth shifts as we grow in our understanding of ourselves and the world. I live by something I once heard Gregory Scofield say, “These are my words for today.” I felt it was important to let everyone know that this is simply what I what I know right now.

RT: Though “the truth” is impossible to achieve, are there ways poetry more effectively approaches it than prose? Or vice versa?

JK: If I can just let myself go and write, “the truth” reveals itself to me. I am often surprised by what comes out and it is through poetry that the most startling things usually present themselves. Perhaps this is because I feel safer writing about abuse and things like metaphysical experiences, visits from the dead, etc. through poetry. In part this is because I do think about my readers and would not want to burden them with trauma that is too explicit. With poetry I can gesture towards things and create an ominous feeling that does not require too many details. I can write into the absence of information and allow my body to tell its story.

. . . it is impossible to “tell the truth” as the truth shifts as we grow in our understanding of ourselves and the world. I live by something I once heard Gregory Scofield say, “These are my words for today.”

My body knows more than I do. It holds ancestral memory, what some call blood memory, and it also holds the cellular memory of my own life. It usually speaks to me through metaphor, and images, which lend themselves to poetry, but I did break with this tradition in the book. In order assist the reader in understanding the effects of the layering of the abuse I have experienced and how it impacted the way I navigated the loss of my two brothers and my mother, I needed to be more explicit. I did this sparingly. Sadly, I have experienced a lot of physical and sexual violence in my life, beginning as a child. I only tell what I feel is necessary to move the story along. Whether that is through poetry or prose is not up to me. I lean in and listen deeply to the story that wants to be told.

I am more comfortable with poetry, but that does not stop me from trying prose. Neale Donald Walsh, the author of Conversations with God once said, “Life begins at the end of your comfort zone.” I would say that some of my best writing has come when I was willing to write outside of my comfort zone.

RT: Speaking of being outside your comfort zone, in her introduction to Standing in a River of Time, Wanda John-Kehewin writes, “Through poetry, Kirton teaches others that it is okay not to feel okay.” That’s a hard lesson to learn, and an equally hard one to teach others. How did you learn this lesson yourself?

JK: When I first entered recovery, I thought that one day I would arrive at normal. I would be healed, and all would be well. That never happened and eventually I began to see the problems with my desire to be “normal” — it was never the right fit for me. I could see that many of the more successful members of my family were boxed in by religious beliefs and colonized thinking that never allow them to feel the freedom that comes with just being human. They were living proof that being judgemental — having the scorched earth thinking that comes with the colonized way of life — burns the one who is judging just as much as the one they judge. Seeing the difference between the way they were with each other and the way my Métis family would tease each other (in a good way) about their faults helped me understand that it is much kinder to myself and others if we accept our imperfections.

RT: Does poetry play a role in reminding you of this?

JK: I think one reason I am so attracted to poetry is that it is filled with possibility, and it attracts others who are considered “rule breakers.” Some like myself are also spiritual seekers. Through teachers like ingrid rose, who offers “writing from the body” workshops, I found that if I can allow myself to enter deep emotions more fully. I can gently excavate the pain that resides in my body. When I do this all the pain, anger, and sadness are moved from my body to the page, where it then becomes a communal experience. It can open conversations, as Otoniya Okot Bitek, a dear poet friend, once said:

“The poet in the Acholi tradition, is not just someone who says the flower is beautiful because it’s beautiful but gathers people to think and talk about whatever it is they’re doing and what’s happening around them… For me, as an Acholi poet, the poem is the container, the space and opportunity for people to gather in community.”

I am not an Acholi poet but I relate to this way of thinking about poetry and the role of the poet in the world. If we can share our brokenness with each other, we will get to see that at times we are all “not okay” and that this is okay.

RT: It’s hard enough to be okay with not being okay inside ourselves; it can be even harder to be open about our not-okayness with others. In Standing in a River of Time you write about your family’s tradition of “respectability politics” and “keeping up appearances.” Most movingly you speak of your mother’s preoccupation with makeup and how, as she was dying in hospital, you were still putting makeup on her whenever your father visited. (“Our attempts look foolish. She looks like the doll I had when I was little.”) Was it difficult to push against that tradition in writing and publishing your life story?

JK: There is no question that I needed to be comfortable with not looking good if I was to publish a book like this. To be fair to others in the book, I needed to divulge details about myself that might shock or upset some of my friends and family. Truth is that my life was always messy and unconventional, but that was not public. I lived a quiet existence and kept a lot to myself. I needed time to get strong enough to not only carry my story to the page but also to do the work that comes after you publish a book like this. I am ready to defend my need to tell what I have told. I could not have done this sooner and I am grateful that I waited. I have a much deeper understanding of it all now that I have lived some years.

RT: What advice would you give to younger writers with similar family upbringings who are hesitant to tell their own stories?

JK: I would say go at your own speed. Trauma is complicated. It will have its tentacles in everything you say and do; this includes your writing. Perhaps you need some distance before sharing your work publicly. Keep some writing for yourself and a trusted few. If you find yourself revisiting the same story over and over, stay with it. There is something it is trying to tell you. Perhaps the earlier versions are not for others but for yourself so that you can write that one version that is the one for the world.

I think it is important to acknowledge that my age does offer me some protection. The things I write about are from long ago and to a certain extent have been resolved. My family is used to me being the one who says the things no one else will say. Not that they like it, but they are over trying to stop me. Some are relieved that someone finally told the truth.

Trauma is complicated. It will have its tentacles in everything you say and do; this includes your writing.

RT: Standing in a River of Time is a book full of ghosts, both literally and figuratively, most notably your aforementioned mother and two brothers, all of whom you lost rather early in life, and your nephew. Sometimes they appear to you as spirits, while at other times their memory and the legacy of their loss are simply omnipresent.

In a poem near the end of the book, “Tumbling,” you write “I have been carrying the dead my whole life // I had to let them go.” In many ways, this book feels like a release of these people, but in other ways a holding on — a calling them back into being. How has writing and publishing this book influenced your relationship with the dead? Do you still feel you’re carrying them?

JK: The poem is not about my nephew Jaime. That grief is still very fresh. I cannot look at a picture of him or see his favourite chocolates at the grocery store without crying. The poem is about how long I grieved about my mother and my two brothers. I knew that my mother never recovered from losing her two sons and that in their short lives they had all experienced unthinkable violence. My brother Murray had run away from home at eighteen and was killed while out East. I couldn’t save him or my mother from my dad’s anger. The poem is really about what I now understand to be survivors’ guilt. Until I wrote the poem, I did not even know that I was sitting with unspoken questions: How can I enjoy my life? How can I forget them and what they experienced? How can I let that guilt go? I did not even know all this was laying below the surface until we did two months of palliative care for Jaime. He was the one that opened my eyes so many things about death and dying, about how clean grief is so very different.

RT: Speaking of opening your eyes, a powerful moment in the book comes when an ER doctor informs you that you’d had your nose broken many times. Only in hearing this do you remember some of your father’s past assaults. Our truths aren’t only hard to communicate, they’re also often hard to know inside ourselves. Did researching and writing this book return memories to you? Did you find the process did more to clarify, or complicate, your sense of your own history?

JK: When I first entered therapy in my early thirties it quickly became obvious that large chunks of my life were not accessible to me. For many years the fact that I could not remember a single bedroom, or classroom, or teacher, was deeply disturbing. What I could remember was brutal. What else was there? My therapist was convinced that I had been sexually abused. Not knowing what has happened to your own body is terrifying. At least it was for me. Not only that, it was problematic when attempting to write about my life. It’s likely the reason I leaned into poetry so much. I didn’t need all the facts. All I needed was the feelings. I could follow the thin threads of what I did know. These days I am okay with not knowing everything.

While writing and researching this book some good memories returned to me. Not only that I began to understand my life in terms of the historical context of my family and my nation. It clarified many things for me, but I still feel incomplete. I have so much more research to do about the Métis and the Icelanders that I descend from.

RT: One way you recounted your memories prior to this memoir was in Step Four in Alcoholics Anonymous’ Twelve Steps: “make a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.” It feels like this was another training ground, or template, for the book you would later write. More broadly, it feels like your journey towards healing taught you as much about how to write this book as your formal literary training. Would you say that’s true?

JK: Absolutely, AA taught me what was important about my story. I have so much gratitude for AA and all who have walked with me there. The twelve steps teach us that honesty, openness, and willingness is the way out of our addiction. Those three traits support me when writing. But it is more than that. We learn to pray daily, to ask for guidance. When writing I ask for a lot of guidance. I take long walks and talk to the trees. I lay tobacco and ask the Creator and my Ancestors for assistance. This is not just my story. It is their story as well. They need to be consulted and I need not only their support, but also the support of the Creator, if I am to be as brave and honest as I hope to be. Staying open, being willing, allowed me to be responsive to the shifts and ruptures that took place.

Standing in a River of Time is an entirely different book than I had originally intended. It is a collaboration between me, my Ancestors, and the universe. As I was writing it, books and stories from friends and family would come to me. I believe these arrived because I prayed and stayed open to what was making its way into my awareness.

Standing in a River of Time is an entirely different book than I had originally intended. It is a collaboration between me, my Ancestors, and the universe.

RT: Your life has been filled both with mentors (Warland, Richard Wagamese, AA sponsors, etc.) and your own mentoring (you describe yourself as a “mother bear” more than once, and not only to your own son!). What do you think makes for the most successful mentors?

JK: I believe the best mentors do not offer much in the way of advice. They mainly teach via storytelling. Any advice they offer is simply a suggestion. They remain open to the fact that you have as much to teach them as they have to teach you. I remember having an AA sponsor who was a bit too heavy handed with their advice. I talked with an old-timer in AA, and he said, “You just tell her that you have lived thirty years and that that experience is worth something.” I don’t know if he knew that what he was doing was not only acknowledging my experience, but he was also validating my own knowingness. I believe that our knowingness is the most precious thing we have and sadly the colonized world is very dismissive of this.

RT: That’s such excellent advice—to think of mentorship as a two-way exchange of knowledge. What do you think makes for the most receptive mentees?

JK: I often tell those I work with to trust themselves. I encourage them to explore their particular gifts. As a mother, I wanted to know who my son was, what gifts did he hold? What does he need from me to allow those gifts to thrive? He is now thirty years old and still calls me for advice about many things. He tells me how much he “likes” me, not just loves me. I do feel that being very thoughtful about what he needed, not what I wanted, made him more receptive to me. I see the same thing happen when I work with writers on their manuscripts. I first interview them, get to know them and their intention for their book before I offer a single suggestion. It’s not about me. It’s their book or in the case of my son, it’s his life. He has his own path; one only he knows.

RT: In the poem “Asking for a Friend” you write that “no degrees but well-read is never enough.” The under-valuing of lived experience in academia is a chronic problem, one felt all the more acutely in Creative Writing, where life experience honing your craft is just about everything! It warmed my heart, then, to see you get a teaching opportunity at UBC. How did it feel to get that position?

JK: It has been a life changing event. I used to dream of being a professor and had no idea that one could be an adjunct professor if they had never been to university. I was stunned when they offered me the position. Turns out those career aptitude tests are right. Mine had always said that I should be a professor.

RT: How has teaching gone for you so far?

JK: The term is over now. It was a challenging time as not only was I teaching at a university for the first time but also I had a husband in the ICU with COVID and we moved into seniors housing while he was there. Admittedly I was a bit wobbly at times, but the students were great to work with and I learned a lot. I would change some things next time but was happy to see that my efforts to decolonize the classroom did bring forth some fantastic poetry. It was an honour to work with them.

RT: You chose to end Standing in a River of Time with a section on forgiveness. Why was that important to you?

JK: I could not figure out how to end the book. Every time I thought I was done there was more to write. None of the new writing felt like an ending. I was past the deadline for the book when I attended a ceremony for the two hundred and fifteen little ones whose unmarked graves were found by the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. Something an Elder said there allowed me to feel more compassion for my dad. After thirty-five years of trying to forgive him, it happened in an instant. It was then that it occurred to me that the whole book was about making my way to forgiveness, not only for others but also for myself. As I reread the chapter today, I saw that I should have said more, but the book was due. Maybe I will write more on this another time.

RT: I think what you’re saying, about your long journey to forgiveness, comes across powerfully in the book. Though I agree you could probably write another whole book on the subject.

In “What Endures” you write “perhaps our wills should say / burn my books especially the journals… let us fade into the foreverness” and in the following poem you write “There is no one here // to correct you. // You can create new pathways, tell new stories.” So many writers turn to writing (and especially writing memoir) in an attempt to last—to transcend death via the page—so it was refreshing to see you, at the end of your own memoir, voicing the opposite. Yet there must be some balance between the two extremes, or else history is completely remade every few years, the lessons of one generation lost on the next. How do you want your book to live in the world?

JK: Words are powerful medicine. They can harm or to heal. Some of the harm comes from disinformation and, as a Métis woman, I have lived in the shadow of disinformation. My earlier writing reflects old understandings, so I do struggle with the idea that some of my writing could live on, as it now feels inaccurate. Adding to this are the feelings that come with telling on someone like a parent. Is it fair to them or to my other family members? And yet, if I and others don’t bring abuse into the open, we are doomed to repeat family patterns and societal wrongs. I do hope my book will help future generations avoid some of the shame I carried. I never wanted the book to be a “how to heal” book, but rather to reflect that it is a long journey, a very personal journey that will be as unique as your particular circumstances.

RT: How do you want your book’s life to end?

JK: I honestly think it is simply a book for “this time.” I doubt it is one of those that should live on. There will be new books, with a deeper understanding of it all. I may be the one tasked with writing one of those books or I may simply have been a stepping stone for the next writer or writers who will see more than I could see now.

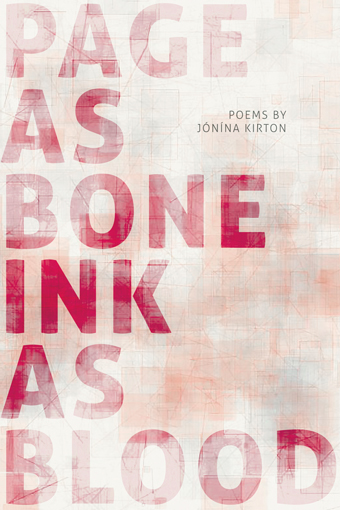

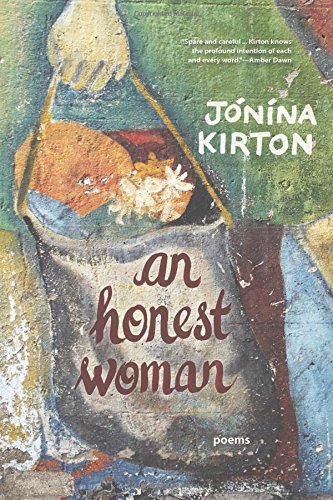

Jónína Kirton is a Red River Métis/Icelandic poet. A late blooming poet, she publisher her first collection of poetry, page as bone ~ ink as blood, in 2014 and was sixty-one when she received the 2016 Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for an Emerging Artist in the Literary Arts category. Her second collection of poetry, An Honest Woman, was a finalist in the 2018 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. She has just released her third book, Standing in a River of Time.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers, was published by Biblioasis in 2021.He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews at: http://roblucastaylor.com/interviews/