The following interview is part two of an eight-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. The series will run from January until the end of April, National Poetry Month. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018)

Late November, -10 C

I forgot to tell you, to say,

(that time you went for so long

came back somewhat changed)

forgot to say:

The barred owl was there

in the paddock at four o’clock

on a stump, hunting mice

catching distilled, chilled amber air.

He lifted off, banked aside the barn,

settled in an aspen by the fence.

Crows massed from nowhere,

everywhere, scolded, circled

as though something

was dead or should be.

The owl slid off the branch

almost liquid

slipped under the bare willow

the swaying heads of grass.

The crows flew east, shed

gloaming from their tails.

I rushed up the hill, up home:

I thought you might be there.

Reprinted with permission from A Sure Connection (Now or Never, 2021).

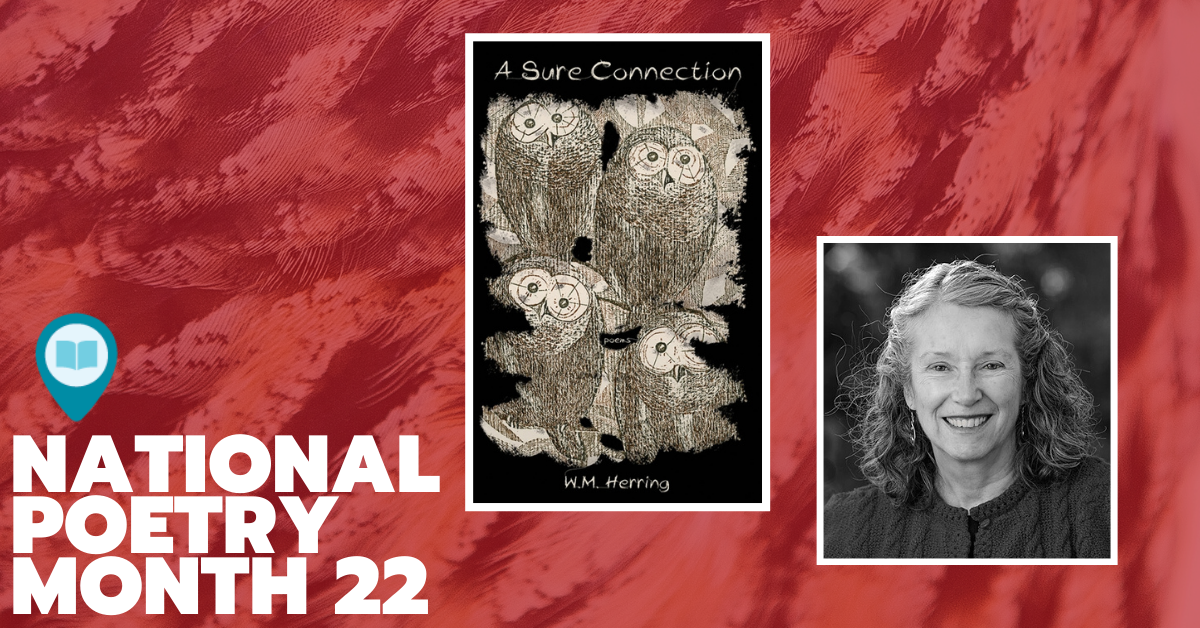

Rob Taylor: Birds of all types appear in A Sure Connection, including the four owls on the cover. Near the end of the book, you seem to acknowledge your obsession via a poem entitled “Another Bird Song.” Why do you think you write so much about birds?

W.M. Herring: I write about birds because I am an observer, and they are everywhere; if you frequent a fairly natural setting and are willing to stay still for a bit, you cannot miss them. Birds differ so much in habitat and habit, yet share so many characteristics. They behave as they were designed to behave, living in a manner that benefits their society. They exhibit beauty in such diverse ways. And, they can fly!

RT: You appear especially drawn to smarter, darker birds like owls and crows.

WMH: Both seem a cut above in complexity and in their ability to reward an observer for their attention. Crows certainly entertain and instruct; that makes them worth writing about. Owls attract because they are enigmatic, riveting, unexpected, otherworldly. An owl sighting pauses everything and makes me take stock of what else is happening, internally and externally, in that moment. I was excited to find Barred Owls in East Sooke as well as in Prince George. I hope the quizzical Barred Owls on the book cover make the potential reader (also) wonder what is within, while providing a broad hint that owls will be involved.

RT: Two other recurring sources of inspiration for the poems in A Sure Connection are photos and fields. The latter can be partially explained by your living at Gleann Eilg, an acreage in East Sooke. Both types of poems involve looking at a still surface and teasing out what’s hidden inside. Could you talk about these two types of poems in your book? What causes you to turn to fields and photos for inspiration?

WMH: I take very few actual photos, but I commit images and incidents to memory for later consideration. The “pictures” so created are starting points, places from which to tease meaning or share delight in the beauty. In “Swimmers,” I talk about my parents through photos that do not exist. What exists are stories they told me and things I observed. Those serve well enough.

The “Gleann Eilg” poems are written at our new place, an old sheep farm in East Sooke, over the course of a couple of years. The other outdoor poems are set almost entirely on a quarter section of overgrown farmland outside Prince George. Thanks to two children, some horses, and a few large energetic dogs, I spent forty years walking that land, watching its inhabitants and the land as it changed. Again, I stored up images and stories, apparently for the time I would finally start writing.

RT: What brought you to finally start writing?

WMH: Retirement brought with it the wonderful gift of time: time to walk slowly, to listen carefully, to contemplate; time to consider a stray thought or to research an event or historical figure; time to daydream; time to wordsmith over a mug of coffee for as long as it takes. In retrospect, I needed time to observe, absorb, and declare before I could produce even the shortest of poems. Until I had that time, I had no idea the writing that would emerge.

RT: Though you didn’t start until retirement, you’ve been observing, absorbing and declaring for a while now! In the acknowledgments at the back of your book, you list magazine publications going back almost a full decade. Did you find it tricky to pull together poems from a decade’s worth of writing, or had your style and themes stayed fairly consistent throughout?

WMH: I wrote my first piece, “Three Black Dogs,” in 2012, the same year it became my first publication in a literary magazine. Eight years later, I pulled the manuscript together. It wasn’t tricky to bring together poems over almost a decade because I am not a prolific writer. I picked poems I particularly liked and thought worth sharing (i.e. that others might find the time spent reading them worthwhile), whether they had achieved publication or not, and I had just enough for a manuscript. The book is a “collected” work — common themes such as family and place are simply common to my work as a whole.

I think my style had not changed much over the years because I started writing so late. My observation skills and worldview had sixty years to mature by then. My writing has become tighter, more spare, over the years; edits to poems in the final manuscript reflect that change and add consistency to the final product.

In retrospect, I needed time to observe, absorb, and declare before I could produce even the shortest of poems.

RT: Most of A Sure Connection feels firmly grounded in British Columbia, but hidden away in A Sure Connection are a number of poems set in far-flung places: Bangladesh, Colombia, England, Germany… And many of these poems seem drawn from your imaginings of historical events. Could you talk about these more wide-ranging poems? How do you think they complement the more here-and-now poems around them?

WMH: The more wide-ranging poems come from people or events, current or historical, that made me stop and think, which in turn made me write. I included them because the interpretation I put on the events is consistent with my worldview, so these poems give a deeper view into the writer’s mindset than a collection of just “family and field” poems could provide.

An important impetus for my writing was a desire to record some stories for my children. “The Councillor,” “Corn in Egypt,” “To The Shops,” “Died of Wounds” and “Swimmers” are among the family history poems. In their telling, they may help readers to recall, reflect upon, and share, their own family stories.

RT: In the poem “The Red Journal,” you write about a book that functions as a “repository for fragments / one per scribbled line,” then provide examples like “snake closet / wood smoke.” I’m curious if this is a real book, and a real part of your writing process.

WMH: The Red Journal is a real book. In Prince George it sat on the breakfast table, at the window overlooking the backyard, forest and fields. The barn was just out of sight. In East Sooke it sits on my laptop table, at a window overlooking a yard, tall stands of trees and the Sooke Basin. As you know from the book, “snake closet” has already made its way into a poem (“Two Snakes”); “wood smoke” is awaiting a poem of its own.

RT: Is this how most of your poems start, in an odd word or phrase you catch and write down?

WMH: The poems start many ways — an image, a word or phrase, a story, a news headline (particularly the odd ones), a first or last line, an idea, a quote, even a poetic device. The germ of a poem is not the problem; bringing it to a meaningful completion is!

RT: One way you move your poems from germ towards completion is via comparisons, either in the poems’ content or structure. It’s right there in the titles of some (“Three Dogs,” “Two Snakes,” “Two Doors”) and also in poems divided into two parts, each providing a different look at the same thing. Still other poems are structured as numbered lists. Is this kind of itemizing and comparing something you pursued consciously over the course of writing this book, or just one of those little surprises that emerges as you pull a manuscript together? What do you think draws you to these types of poems?

WMH: Aha — you have found evidence and are looking for root causes! Good sleuthing. My brain is wired for logic — comparing and contrasting, counting, listing, parsing, ranking and evaluating. I have no training in Creative Writing, and no studies in literature beyond second year English. I have a degree in Computer Science and spent many years in software development, training, technical writing, and business analysis. Itemising and comparing is not so much conscious as inevitable. The result of all this: I find logical constructs pleasing. That and clean simple words, tight language. I am not completely left-brain, but there are those who would attest that I lean that way.

The germ of a poem is not the problem; bringing it to a meaningful completion is!

RT: Ha! Some poets could use their “left brains” more often — it might help me have a clue what they’re saying!

In “Singing” you write about someone singing while walking alone at their farm: “Why do I suppose joy / brings these songs? // She is singing to the bears.” I love the duality there, singing joyfully to the bears both to please them and to keep them away. I’m tempted to read “Singing” as a bit of an ars poetica: we poets keep death at bay by joyfully singing to it. Would you say that when you write a poem you are singing to the bears?

WMH: Your questions illustrated one gratifying element of presenting poems to others: the reader finds interpretations that the poet had not intended, or possibly just not noticed, but that work. I love that because it shows how utterly a poem can make the reader part of the process. The poem then carries different meaning for different readers.

Singing to the bears lets them know I know that I am in their territory, but intend them no harm. The song builds a congenial barrier. The poem sings to the reader, drawing them into the experience. The poem also sings because it calls out to be read and heard. You are never done with a poem (writing or experiencing it) until you have read it aloud or heard it read.

W.M. Herring was born in Quebec, grew up in Vancouver, and now lives at tidewater in East Sooke on Vancouver Island. Her work has been published in various literary journals including The Antigonish Review, ARC Poetry, Canadian Woman Studies, Literary Review of Canada and Queen’s Quarterly. A Sure Connection is her first collection.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸was published by Biblioasis in 2021. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews at: http://roblucastaylor.com/interviews/