The following interview is part eight of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2021. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

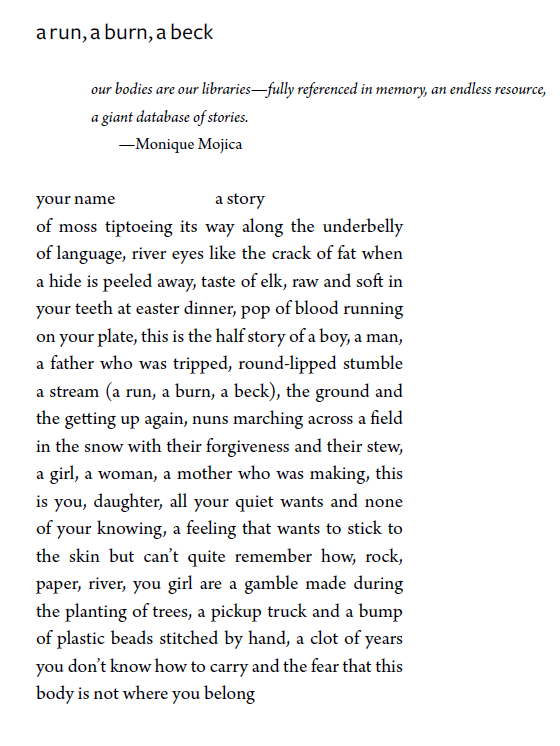

Reprinted with permission from Undoing Hours (Nightwood Editions, 2021).

Rob Taylor: Early in Undoing Hours you write about a kid “learn[ing] quick that being native is okay as long as you aren’t too native, as long as your skin is as yt as it is, as long as you’re pretty, and you fit in with the other yt kids, and you don’t talk much, don’t make ppl uncomfortable…” The poem that’s from is entitled “how to find your father,” and it feels to me like the theme of “finding” (the Cree language, your father, yourself) sits at the very heart of Undoing Hours. Could you talk a little about your life before all the “finding” explored in the book, and how it prepared you (or didn’t prepare you) for what was to come?

Selina Boan: It is exciting to hear different interpretations of Undoing Hours. This is my debut collection and getting the chance to learn how my work translates is a special (and wild) experience.

For me, I don’t think about my experience of learning as a “before” or “after” – nêhiyawêwin and my identity as a nehiyaw has always been a part of my life and who I am. I grew up with my mom and step/adoptive dad on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the Cowichan Tribes and observed an immense amount of racism towards Indigenous folks in our community. I am light-skinned and move through the world with white privilege. Observing so much racism in our community made me very aware of that privilege, though I didn’t necessarily have the language for that feeling yet. For me, the book is less about “finding” and more about reclaiming/claiming what has been historically stolen from me and my family as nehiyaw.

RT: That’s a good clarification – thank you! Undoing Hours explores this process of reclaiming/reconnecting with both people in your family and nêhiyawêwin (the Cree language). Could you talk a little about the chicken-and-the-egg of it? Did one journey inspire the other, and how did each journey influence the other as you went along?

SB: I have always wanted to learn nêhiyawêwin but it took me a long time to gain the confidence to try. Reconnecting with my father and that side of my family helped me build that confidence. I initially began trying to teach myself nêhiyawêwin from the internet and resource books. It was a starting place (and there are so many wonderful resources available) but language learning is so much more than just looking words up in a dictionary. nêhiyawêwin comes from the land and so learning is intrinsically tied to reciprocity, community, and place; I am so grateful to the Elders and knowledge keepers who I am currently learning from. nêhiyawêwin is such a beautiful language with so many different dialects and variations depending what community you come from. As with any language, there are often words or ideas that don’t translate. Language is central to the way we view and construct the world around us.

language learning is so much more than just looking words up in a dictionary or studying from a workbook. nêhiyawêwin comes from the land and our people and so learning is intrinsically tied to reciprocity, community, and place

RT: At one point, you write “what i’m trying to say / is english is failing me” – did nêhiyawêwin help fill the gaps?

SB: There is inherent tension and violence between English and nêhiyawêwin, a tension I think about a lot given my work as a writer. nêhiyawêwin was spoken by my nohkom and nimosom. As a result of residential school and other assimilation tactics used by the Canadian government, my father can understand nêhiyawêwin but is not a fluent speaker. Language learning for me is one way to connect and empower myself while challenging assimilation policies on my own being and the landscapes I inhabit. It is about being able to communicate with Elders and with ancestors in our own language. Throughout the collection, I experimented with forms as one way to think about the ways language and naming yield power and inform identity, memory, and cultural knowledge.

RT: Let’s talk about some of those formal experimentations! In Undoing Hours, stanzas roam about the page, large gaps or caesuras appear within lines, and one sequence in the book is even printed sideways to allow for very long lines running down the page. Perhaps most intriguing of all is your use of front slashes (“/”), which are usually reserved to mark line breaks, as additional punctuation within lineated poems. For instance, the first poem in Undoing Hours opens:

ask / what is the history / of a word / a lake of commas /

a pause in the muscle of night / a dry river and the snow it

holds / …

It feels to me like there are alternate (skinnier) versions of these poems hidden within the larger poems! What inspired you to make this formal choice? Do you just like line breaks so much that you couldn’t get enough?

SB: Ha ha, I love this question! I love the formal possibilities within poetry and I am often drawn towards work that takes formal risks: Jordan Abel, jaye simpson, Justin Philip Reed, Layli Long Soldier, Aisha Sasha John, Joshua Whitehead (to name only a few!). I have always been led by sound in my poetry, so experimenting with the slashes was connected to the way I was hearing a poem out loud. I first saw slashes used by Sandra Ridley (my very first poetry teacher) and it felt like something cracked open for me. I also love the way they visually break up a poem on the page. To be honest, many of my first drafts emerged in this slash form and it wasn’t until later that I changed the form or lineated them.

I was once told that slashes in poetry are “unearned” and I spent a lot of time thinking about that. To be honest, it took me a while to trust my own instincts. I was very lucky I got the opportunity to go to Banff for the writing residency in 2019, where I got to nerd out with the other poets about form and punctuation. I often laugh, thinking about the amount of time poets spend thinking about slashes, or the particular placement of a comma or pause. It sounds like a ridiculous way to spend your time, and yet it can be those subtle choices that help guide the sound and feel of a poem dramatically.

RT: You’re talking to the wrong person if you want to suggest thinking about punctuation is ridiculous! I have to restrain myself from not exclusively talking about this stuff. Could you talk a little about what drew you to some of your other formal choices?

SB: Ha ha, same. Many of the forms stemmed from my attempts to show the messiness of language learning, of grief, of heartbreak, of making mistakes. I also wanted to play with the blurring of time and the idea of “undoing” within the book. Form was a great way to move towards those themes.

RT: There’s something very “honest” about these choices – we are on an imperfect journey with you, and the imperfection of it makes it all the more real or “truthful.” Poetry, though,is of course in no way obligated to tell “the truth!”

Near the end of the book, you write that “i’ve decided not to tell / the whole story as i know it,” and soon after, “forgive me, i don’t remember… which lie i kept // which truth i made.” Could you talk about “the truth” in this book? How does its “truth,” recorded in poems, differ from the “truth” of autobiography?

SB: Two of my mentors, Sheryda Warrener and Aisha Sasha John, read my work-in-progress and pushed the manuscript into a new place. They reminded me that I had to put my guts (my whole self) into the work I was making; they could tell I had been holding back. This is where the spine or “truth” of a poem lies for me—at the emotional centre. That kind of truth is one that I feel in my whole body when I’m reading a brilliant poem. It can be hard to go into the places a poem might require. I struggled and worked hard to try and do that with the poems in this collection, while also maintaining my own boundaries about what it is I wanted to share.

I sometimes changed specific details in the book, or added images, to help build and create space for the emotional centre of a poem. Our memories are fluid and what one person remembers about an event, another will not; even within autobiographical non-fiction there is always a selected narrative, there is always something left out, or altered, there is always limitation. Towards the final stages of editing, I took out a lot of specific details, sometimes to the detriment of the poem, but I wanted to respect my own boundaries and the stories of people I love and care for. It is so important in my work that I am actively caring for the people I love alongside making work that is emotionally honest.

Towards the final stages of editing, I took out a lot of specific details, sometimes to the detriment of the poem, but I wanted to respect my own boundaries and the stories of people I love and care for.

RT: In a number of poems in Undoing Hours, we witness the speaker thinking through many of the decisions you spoke of just now (poetry’s “truths,” what should be told, what should be withheld, etc.). In these poems, the act of choosing to turn a lived experience into a poem is stated directly (for instance, “i write the moment in a poem and send it / to you”).

As I read the book, I became more and more conscious of the decision at the heart of any poem: the poet chose to record this particular moment, in this particular way, over and above many others. This opens up big questions: what is recorded, what is withheld (“i know you want / the piece of the story // that is clandestine / but i won’t give it to you // & i’m not sorry), and why record it in poetry? In “email drafts to nohtâwiy,” you write “i’ll admit, i’ve been afraid to write. so here is my deflection, for everyone to read.” What parts of your life do you find easier, or perhaps more necessary, to “deflect” into poems? What does turning a moment into a poem open up for you? What does it close off?

SB: So much of my writing in this book circles in on identity; what it means to contribute to community, how to negotiate my position as both a settler and an urban nehiyaw, how to be mindful of where I come from, how I was raised, and how I am learning. I spent a lot of time thinking about the ways in which I wanted to approach telling these stories.

In the poem, “email drafts to nohtâwiy” and throughout the book, I wanted to be transparent about the performative aspect of making a poem. As with any story, there is always something withheld. The moments in the poem where I directly address the reader became a way to nod towards the absurdity of poem-making. Many of the poems in this collection feel vulnerable and intimate to me. They hold parts of my heart and they were really hard to write. Those deflections and acknowledgements are ways for me to guard myself a bit, and to remind readers that while I am revealing intimate moments or emotions, I am still in control of what I share. This felt especially important given the history of Indigenous stories being consumed, stolen, and maltreated. I would say it offered a sense of empowerment during the writing process as well as catharsis.

So much of my writing in this book circles in on identity; what it means to contribute to community, how to negotiate my position as both a settler and an urban nehiyaw, how to be mindful of where I come from, how I was raised, and how I am learning. I spent a lot of time thinking about the ways in which I wanted to approach telling these stories.

RT: I love that answer. Your control over the poems is clear throughout the book. At the same time, this is a book about taking on new, hard-to-control challenges in language: a first poetry book about learning a new language (nêhiyawêwin), when poetry itself is, in its ways, also a new language!

You studied Creative Writing at UBC in the years leading up to this book, and many of your classmates and teachers are thanked in the book’s acknowledgements. Were you learning the two “languages” concurrently? What did learning nêhiyawêwin bring to your thinking about poetry, and vice-versa?

SB: I love thinking about poetry that way! It reminds me of conversations I have with some of the youth I teach poetry to. Poetry doesn’t always have to make “sense” in order for it to hold emotional weight or feeling. The same can be said for learning a new language—though you don’t necessarily know yet what exactly is being said, you can feel and know the language in your body. That has been my experience with nêhiyawêwin.

That said, I don’t want to over-romanticize language learning. This book was also written to show the messy, sometimes hilarious, journey to learn one’s own language. I wanted to celebrate nêhiyawêwin while being transparent about the process—it is really hard to learn a language! My dream is to one day be able to speak to my kohkum through dreams in the language she spoke.

Poetry doesn’t always have to make “sense” in order for it to hold emotional weight or feeling.

RT: What a beautiful, beautiful dream. As you say, the book takes a variety of approaches to its subjects: sometimes romantic, sometimes messy, sometimes hilarious (or all three!). Reading Undoing Hours sometimes felt like reading a series of interrelated chapbooks. The book features a number of sequences that are formally distinct, as well as long poems.

It could have felt like a bit of a Frankenstein project, awkwardly stitching all those pieces together, and yet it doesn’t at all: the through-line of language and family is both clear and powerful. Did you always have a sense of how you would structure the book? In your acknowledgements you thank “Shaun” (Robinson, I assume) for his “brilliant editorial eye,” noting that he “gave [Undoing Hours] a shape.” Could you talk a little about how he helped you pull everything together?

SB: I knew I wanted Shaun Robinson to help edit this book and was very lucky he agreed to help. I wanted the structure of the book to play into the blurring of time (the undoing of time) but I wasn’t sure how far to push it or how to achieve that. Shaun has a particular way of looking at a poem—he turns the poem over and is able to see it from all sides. He meets poems where they are and finds a way to nudge you toward the gut, or centre, of a poem. We also have very different poetic styles and I wanted his perspective on the collection.

In particular, he offered several ideas about how to structure the book that were immensely helpful. He helped build a loose narrative spine for a book to help guide the reader. I also want to mention he recently published a book called If You Discover a Fire, out with Brick Books, and I cannot recommend it enough. His poems do such unexpected and delightful things with images.

RT: I couldn’t agree more! I have an interview with Shaun about If You Discover a Fire coming out in the fall with CV2. Shaun’s book came out a season before yours, but he wasn’t your only UBC colleague working on a book around the same time! Also in your acknowledgments, you thank “Molly” (Cross-Blanchard, I assume), saying that you’re “so grateful to have gone through this book journey with [her].” Molly’s debut collection, Exhibitionist (Coach House Books), is also being published this month. Could you talk about working your way to your first books together? Did your conversations before and during the making of your books shape how you thought about the process, or your book itself?

SB: I feel so lucky to have gone through this experience with Molly. Towards the end of the editing process with our respective publishers, we decided to exchange manuscripts to help one another with edits and book structure. It was the first time I had read her manuscript the entire way through and I was blown away—I laughed, I cried. I felt the whole book in my gut in the best way possible. She uses humour in a way I could only dream of. Her poems are tender, raunchy, and moving. We have very different styles of poetry and she proved to be one of the most invaluable editors to my book. She offered some truly brilliant last minute edits to poems in the collection I was still struggling to get “right.” I have to thank her for answering those late-night panicked text messages and phone calls. It was so special to have a friend to go through this process with. Go buy her book. You will not regret it.

Speaking of the writing and editing process, I also want to mention Brandi Bird, who is another person who had a huge influence on this book. When I first met Brandi, I was in awe of their poetry and immediately felt connected to their work. This book truly wouldn’t be what it is without them. They helped me with a lot of the early drafts of this collection. They would look at one of my poems and understand what I was trying (but often still failing) to do, and help me push the poem into that sweet spot.

RT: Brandi’s work will be getting some love in the closing post of our series, coming in a couple days! Speaking of all this editing work, you yourself have worked as an editor at PRISM international, and now serve both as a poetry editor at Rahila’s Ghost Press and Room Magazine. Could you speak about the role of editing and publishing others within your creative life? Is there some balance you’re interested in there, between publishing your own writing and the writing of others?

SB: Honestly, it may sound cheesy but I feel so lucky to have the opportunity to work with so many incredible poets and writers through my editing work at Rahila’s Ghost Press and Room Magazine. I approach editing the same way I approach my own poem-making. I ask a lot of questions, to both the writer and the work itself. My goal is to get the work to a place the writer feels good about. That is my priority. Everyone deserves their work to be seen and held in a way that expresses care and meets the work where it is at. In my experience as a writer, we usually know when a poem has “landed” or not. As an editor, my goal is to help guide a poem or collection to that place so that the writer I’m working with has that feeling at the end of their project or piece.

As an editor, I learn something new from every writer I work with. I don’t think I’d be doing my job properly if I didn’t feel that way. I have the privilege of editing work that I want to see more of in the world and believe so deeply in. Reciprocity and community are very important to me and as I move forward in my career, I know that mentorship in an editorial capacity will continue to be something I dedicate time and energy to.

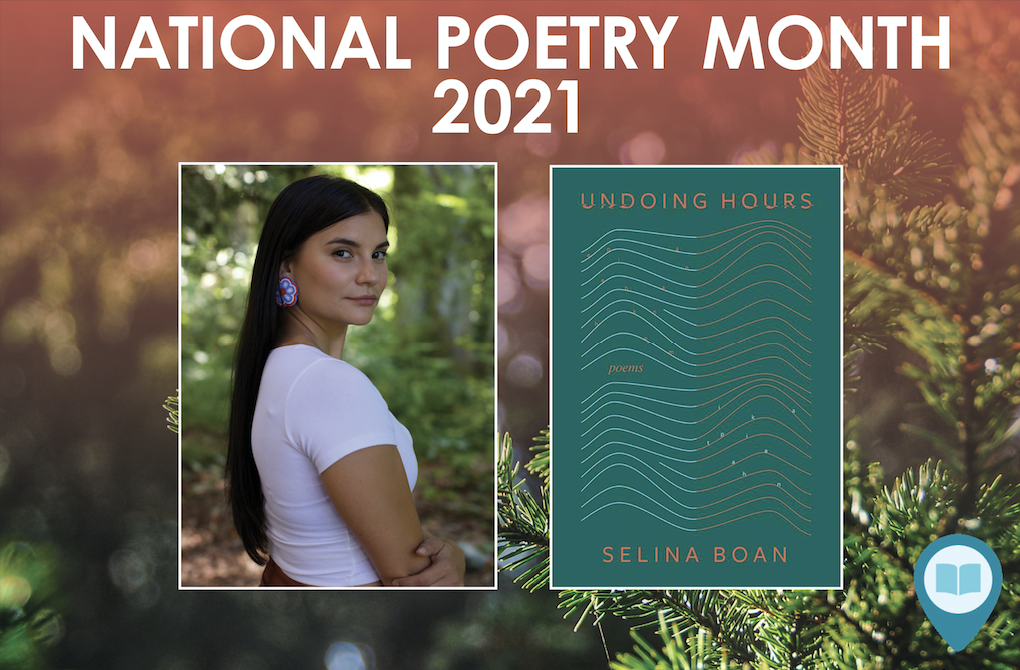

Selina Boan is a white settler–nehiyaw poet living on the traditional, unceded territories of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), səl̓ílwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh), and sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) peoples. Her work has been published widely, including in Best Canadian Poetry 2018 and 2020. She has received several honours for her work, including Room’s 2018 Emerging Writer Award and the 2017 National Magazine Award for Poetry. She is currently a poetry editor for Rahila’s Ghost Press and a member of the Growing Room Collective.

Rob Taylor is the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). His fourth poetry collection, Strangers, was published this month by Biblioasis. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.