The following interview is part six of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2021. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Porcupine IV

my kôhkom’s tongue cuts through the air like a helicopter blade

thrumming acerbic nursery mobile a bed fit to curse you with a spell

no roadside crystals can remedy a burial ground full of hipster

dream-catcher tattoos & smudge kits bought off Amazon for $19.99

the cure for existential angst not for sale here vituperative stones fall

from round mouths looking for gemstones millstones she’ll let you

gawk as long as you drown while you do it

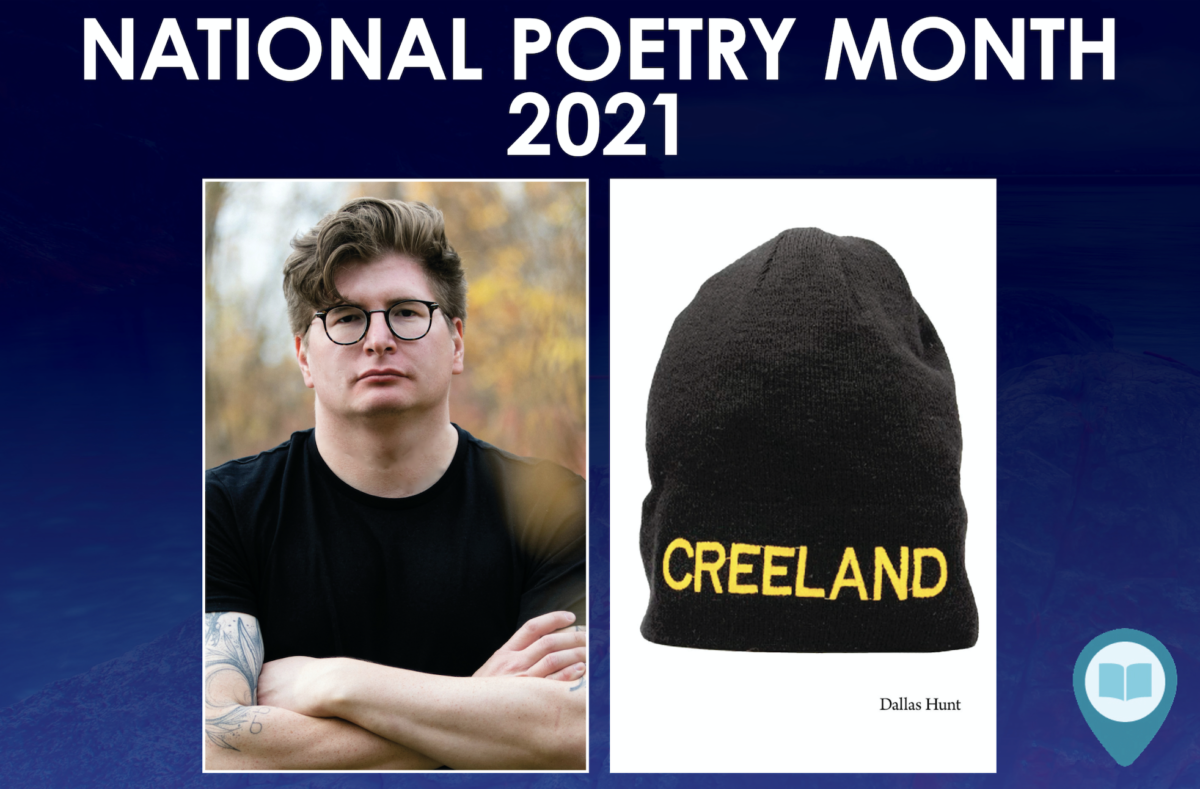

Reprinted with permission from CREELAND (Nightwood Editions, 2021).

Rob Taylor: I’ve loved your writing for a number of years now, and I’m so glad we get to chat about your first book, CREELAND. I think the first thing of yours that I encountered was your “Cree word of the day” tweets: since 2015, you’ve been sporadically posting Cree words connected to popular topics of the day. Most recently, following Joe Biden’s inauguration, your tweet on the Cree phrase for “Bernie sits” (“apiw Bernie”) was liked over 2,000 times!

The theme of translation between Cree and English is also central to CREELAND. The book presents various forms of translation, from the more traditional glossary of Cree words in the endnotes (which, notably, only translates a selection of the Cree words used in CREELAND), to poems like “Cree Dictionary,” which provide less literal “translations” (“the translation for joy / in Cree is a fried bologna sandwich”, “the translation for evil / in Cree is the act of not calling / your mother on a Sunday”, etc.).

In exploring both technical translations and “translations” that capture the feeling of a word, CREELAND reminded me of the choice the poet Don Paterson once said must be made by all translators between honouring “the word or the spirit” of the original text – if a translator attempts both equally, “we are likely to come away with nothing.” A poem can be “right” in certain ways a dictionary can’t, and vice versa. Could you talk a little about your approach to translation in CREELAND?

Dallas Hunt: I think that in many ways most of the translations are “imperfect” (in “Cree Dictionary,” purposefully so) and that’s fine. I mostly post things on social media to increase my own vocabulary or to work on my verb conjugation. That said, I think there is much about “Cree life” that can’t be fully captured in the language—things spill over and exceed—so I try to get at those feelings with the language I have available to me. It’s never enough, but I’m fine with that.

RT: The limitations of what language can and can’t accomplish is certainly another theme in the book. One of the (darkly) funniest lines in CREELAND comes in “Entry Four”: “Every time I write “kôhkom,” / some settler, somewhere, / cums.” We’re in a time where there is a desire among many settlers to understand and “consume” Indigenous culture, but this engagement happens under the consumer’s terms. Certain subjects/words are fetishized, others ignored (your poem “Curriculum of the Wait” explores how “every ndn poem / is about residential schools” – alongside every novel, play, memoir, etc.). All writers face the mixed blessing that their words will go out in the world, unchaperoned, to be used and interpreted as the reader sees fit, but in your case this process seems particularly fraught.

Could you talk a little about how you would ideally like the Cree language, as presented in CREELAND, to be engaged with by settler readers?

DH: The language is going to be engaged with however the reader sees fit. One thing I do like, though, is that more people appear to be seeing Cree as a “living language,” so I guess in the grand scheme of things, as long as people see our languages (and us) as alive, there really isn’t much more I could hope for. I do think that there are “particular” forms in which Indigenous peoples are legible (like through language), so that’s something I do try to complicate in the collection. If people take notice of that, great, but I do have a bit of an ambivalence toward it, too (not to be overly obscure or combative!).

RT: Fair enough! Could you talk a little more about complicating the ways Indigenous people are “legible”?

DH: I think that non-Indigenous peoples are more than willing to interpret us through particular lenses (e.g., language, residential schools, “culture”) but are far less willing to take our political assertions seriously. I think whether we’re in rural, reserve, or urban environments, Indigenous peoples are constantly asserting a politics that is so summarily dismissed, sometimes in favour of something as capacious as “culture,” that we’re not being really heard or engaged with. Engage with us—our politics, our assertions, our communities. We’re not going anywhere, so it might be prudent to do so.

I think that non-Indigenous peoples are more than willing to interpret us through particular lenses (e.g., language, residential schools, “culture”) but are far less willing to take our political assertions seriously.

RT: What do you hope for Cree speakers to find in these poems?

DH: The collection is about everyday Cree economies of care. I hope there is some recognition there, disagreement, even contention—we are vast, complex and varying communities, so I hope some Cree people (and other Indigenous peoples) appreciate the writing. But I also hope that, if I were there, Cree and Indigenous peoples would argue with me about some of the articulations or interpretations of things in the collection. That’s what being in community or visiting as a method is all about.

RT: One way language, community and politics come together in CREELAND is in what I think of as your “dictionary” poems: list poems that explore the meaning of a particular term from various angles. Some of the most joyful, and angriest, moments in the book come in list poems like “Cree Dictionary” (“the translation for X is…”), “Mozart, Saskatchewan” (“a white man is…”), and “kôhkom Freedom” (“freedom is…”).

“Cree Dictionary,” from which I’ve already quoted, is filled with humourous lines, while “Mozart, Sasktachewan” opens with “a white man is a fist / that ends families” and “kôhkom Freedom” closes with “and / fuck them / anyway”—possibly the greatest ending of a book ever! Another, from the list poem “Nathan Apodaca”: “I wish I cared about anything as much as white people care about toilet paper.”

What draws you to these kinds of list poems? Is there something about the non-narrative way they approach their subjects that allows you to tap into a deeper vein of humour and anger?

DH: Wow, Rob, I like how much you’re nudging me to think about form here. Ha ha. Some of the poems you’ve listed here I don’t actually consider list poems, though I do think the repetition might frame them that way—an interesting thing to think about. I guess generally I like repetition as a rhetorical device, and that it may have the potential to “open things up” or really emphasize a particular idea or concept. In a sense that might not be particularly subtle, but I don’t think CREELAND is subtle at points. Sometimes I do feel joy or anger or a variety of feelings, and I guess the repetition of words or phrases articulates that (betraying me in the process).

RT: So many books these days are in one mode: subtle or not, a whisper or a shout. It’s refreshing to read a book that both embraces subtlety and sets it aside when the poet really needs to make a joyful or anger-filled point.

The joy and anger in the book seem to converge near the end of CREELAND in poems that focus on Indigenous futurities (“futures whose / formation(s) / make another / one hundred and / fifty years impossible”) and, more broadly, desire: desires for a people, and for oneself, both now and in the future (“desire / is a struggling river”). Could you talk a little about desire and futurity as themes in the book, and in your life?

DH: Desire and the future share a particular terrain—I think as Indigenous peoples we’re constantly desiring a different future, one that looks radically different from the present (and orients how we act in the present, hopefully). I’m someone who constantly thinks of the future, but I also understand desire and its entanglements—how in many ways, we have no control over our desires. So the desire I write about in the text is deeply personal, but it also is this gesturing out to different horizons. What do we want, what have we internalized, and how do we disentangle how we’ve got here? They’re massive, capacious, but intensely personal and intimate questions, so I guess if I want the book to do anything in this instance, it’s to get us all to think through these questions a bit more.

RT: You have an obvious love of massive, capacious questions: in addition to being a poet, you are also an academic and activist. Your politics are thoughtfully and powerfully presented throughout the book, and many of the poems – about settler colonialism, the prison-industrial complex, etc. – could easily have been “translated” into essays. In “Small” you write:

yes, i don’t mind

feeling small

’cause you can

see, and plot,

a lot from down here.

That poem isn’t an ars poetica, per se, but I wonder to what extent it ties into your thoughts about genre – choosing poetry over, or in accompaniment to, other forms of writing. What led you to poetry, small as it is, as a way to explore such big ideas?

DH: I started to write poetry when I was reading a lot of criticism and theory. I was trying to finish up my comprehensive exams for my PhD and found my desire for academic writing waning. What I did in response was to start to write poetry, and I found a lot of the concepts I was encountering in my scholarly work were coming through in my poetry. Thankfully, though, some of it was not, and I got to explore issues or themes that I never would have in an academic article. Poetry also enabled me to start writing about myself and using that first-person pronoun “I” (for better or worse). While the speakers in my poems are not always me, I am grateful to be able to use that “I” (or “i”) in poetry now. I guess I have theory to thank for that, which is probably the first time anyone has ever said that.

RT: Ha! It’s interesting that theory brought you to the personal, the “I,” and now the personal in CREELAND returns the favour, helping bring the theoretical concerns that underpin the book to the reader. Poems like “Spiraling (Fine for Now)” and “I Almost Had a Mental Breakdown During My Master’s Degree” firmly place your personal mental health struggles amidst these larger theoretical and political ideas. How do you think these poems shape the poems around them?

DH: I think that it’s a perfectly rational response to the current conditions we occupy to have to deal with mental illness. I have for a while and know personally that a lot of Indigenous peoples deal with these issues in a far more severe way than I do (in ways that are legible or make sense to me). I guess in writing about mental illness, I wanted to illustrate how it’s a part of the colonial process—that these issues aren’t just structural, but rather play a huge part on the personal and collective psyche of Indigenous peoples and communities. We have a lot to contend with here. I also think we’re at a place now where we can talk about mental health openly (or, at least, I hope that’s the case), and I guess I wanted those poems to catalogue how I felt at particular times and how it is okay to feel those ways. One of the things a therapist said to me that still resonates is that “it’s okay to feel anxious,” and that reoriented so much for me. I’m not perfect in any way, but I’m interested in how this world, in a sense, can feel far less lonely.

in writing about mental illness, I wanted to illustrate how it’s a part of the colonial process—that these issues aren’t just structural, but rather play a huge part on the personal and collective psyche of Indigenous peoples and communities.

RT: Did the learning you acquired while writing CREELAND help you think about your academic writing in new ways?

DH: Interesting question! I guess I’m far more attuned to form while writing academic articles and, depending on the publication, might be far more adventurous in how I write or construct certain arguments. I’m a big fan of the theoretical writing of Saidiya Hartman and Fred Moten and would like to have my critical writing be anywhere near as poetic as their writings are (this is a doomed project, I know, but I love their texts and want to have that wedding of poetics and theory at the base of my writings. I’ll fail, I know, but how lovely it is to try!).

RT: In one of your poems that could easily have been turned into an academic article, “There Are No Good Settlers,” you write about the problem of “woefully unprepared” institutions deciding if someone is “‘Indigenous enough’ for a title or position” (including people who claim Indigeneity to “help them in this institutional moment”). In the poem you suggest that “perhaps a poetics of accountability can allow us to see each other differently.” Could you talk a little more about a poetics of accountability, and what role poetry, or poetic thinking, can play in dealing with this issue?

DH: These issues can be touchy or hard to talk about at times. There’s something about the obliqueness of poetry, of how it can come at an issue from a different or interesting angle (a parallax view), that I think allows us to be able to have hard conversations that we might not in alternate arenas. I do think we’re in a particular moment (this “reconciliatory” moment) that has allowed people to attain a certain level of peace, but has also enabled others to attempt to capitalize on the violences Indigenous peoples have endured historically. And while I know that might be an incendiary statement, I think all of us, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, might recognize this to be true. In fact, there have been a few high-profile cases of this recently in the art world and I think, ultimately, it hurts Indigenous peoples a great deal more than people think.

RT: Not incendiary at all. One of the many downsides to these false claims is that they eat up space that should be given to deserving Indigenous artists. It’s wonderful to see that, in addition to publishing your own book this year, you’re also making space for another Indigenous poet who is well worth celebrating: (Re)Generation: The Poetry of Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm, a selection of Akiweznie-Damm’s poetry which you edited, will be published in August from Wilfred Laurier Press. Could you talk a little about that book and the influence Akiwenzie-Damm’s poetry has had on your own writing?

DH: Kateri is a great writer. It was an enjoyable process to inhabit someone else’s thinking and poetic works and try to think through how they wrote a piece—the why and how of it. In many ways, Kateri’s project has been great because I’ve been given the chance to become more familiar with a writer I wasn’t completely familiar with before. If you have a chance, read Kateri’s work, especially her erotic work, because I think it’s incredibly generative and courageous (a lot of us don’t write about sex, but Kateri has no qualms about it and I really admire it).

RT: In your introduction to (Re)Generation, you talk about Akiwenzie-Damm’s connections to spoken word and performance. While most of your poems seem designed for the page, one way the spoken and sung makes its way into your book is through rock music: Daughters, Sufjan Stevens, Talking Heads, Chris Gaines, and even Fleetwood Mac (via-Nathan Apodaca’s-Cranberry-Juice-Skateboard viral video), all make appearances in epigraphs, poem titles, etc. What role do music and lyricism play in your thinking about poetry, and your writing process? Is something always playing in the background as you write?

DH: Interesting question! I’m responding to these questions while listening to Tei Shi’s “Even if it Hurts” on repeat. Ha ha. Sometimes, I think, I write to music, but other times I’m in bed in total silence or having a morning coffee and reading something. The weird thing is that my musical interests verge towards hip hop or R&B, so I guess the rock bands are a surprise to me (though not untrue). I like music, I play music occasionally, and I guess I wanted to acknowledge what I was writing to at particular times (I learned this from Richard Van Camp—who you should read if you haven’t already!—because I think he lists what he was listening to while he composed certain pieces). Leanne Simpson also borrows from songs for titles and other things (I’m thinking of “It Takes an Ocean Not to Break,” Leanne’s short story which is titled after a song by The National). Anyway, I guess those are gestures to particular writers who have influenced me.

RT: Do you see a through-line there of some sort, from Indigenous oral traditions, to performance-oriented poets of previous generations (like Akiwenzie-Damm), to Richard Van Camp’s notes and Leanne Simpson’s songs and stories, to your listening to Tei Shi on repeat?

DH: That could be true, yes. I mean, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that both Kateri and Leanne have made musical renditions of their written, creative works. Richard, too, acknowledges the music he has written to as well, and I think what this might all speak to is the way we acknowledge one another and pay respect to inspiration and its sources. Generally, for Indigenous peoples, we gesture to where particular forms of knowledge come from, and song is a form of knowledge.

for Indigenous peoples, we gesture to where particular forms of knowledge come from, and song is a form of knowledge.

RT: In CREELAND you make far more use of the blank space on a page of poetry than many poets. Poems shift from left to right margins, or are split between the two, creating huge gaps in the middle of your lines. Other poems are simply presented with very short lines, a handful of words running down the left margin. What is the importance of line breaks, gaps and silences in your poems? What do they allow you to say/do in your poems that would be otherwise unavailable to you?

DH: Some of this is aesthetic—I like the sparseness. Part of that is reflected in the cover as well. But I also think particular words or lines function better as standalone phrases or even objects. I like the idea of dwelling, and I think sometimes it’s easier to dwell in a particular narrative or spatial sense if a word or line is on its own. It’s an invitation to dwell.

RT: Circling back to Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm, in addition to being a poet she is also an organizer: in the early 1990s, she both founded the Indigenous publisher Kegedonce Press and co-founded the Writers Independent Native Organization (WINO). These organizations helped foster a generation of Indigenous writers (and Kegedonce continues to do the same to this day!). Here in 2021 we see another generation of Indigenous poets, thriving perhaps like no other, many of whom you thank at the back of your book (Jessica Johns, Selina Boan, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Brandi Bird, Jordan Abel…). There’s a tendency to treat these cultural “moments” as spontaneous, almost magical occurrences, overlooking all the work done by previous generations to prepare their coming.

DH: There are so many amazing Indigenous poets at this particular moment. That said, I think you’re right in saying that there is a long lineage of Indigenous writers who have paved the way for many of us. Also, there is this term that emerges in relation to Indigenous writing—”renaissance”—that I think is deeply problematic and doesn’t gesture to the peoples who have been writing for decades (Linda Hogan, Chrystos, Eden Robinson, among others). I also think we need to be attentive to this moment, and why audiences might be interested in this particular work at this time (that reconciliatory moment I spoke to before). I don’t say this to disparage anyone’s writing, but rather to get us to think about Indigenous knowledge and cultural production and its palatability at this point. Why are readers engaging with us and how, and what affective attachments, investments, or desires might they have? Will they be reading us in ten years?

there is this term that emerges in relation to Indigenous writing—”renaissance”—that I think is deeply problematic and doesn’t gesture to the peoples who have been writing for decades

RT: Do you think Indigenous creators can transform this reconciliatory moment into something more lasting? Or do you think that will come down to the will and desires of settler readers, funders, etc.?

DH: In many ways, this is the conversation or question facing many Indigenous peoples, both academically and in artistic circles. I think we’re starting to write for one another, outside of the eyes of settler readers, and I think it’s a beautiful thing. I’m happy I get to read Indigenous poets and writers while listening to Jeremy Dutcher or Black Belt Eagle Scout—it’s a wonderful space to dwell in. I think I’ll stay here awhile.

Dallas Hunt is Cree and a member of Wapsewsipi (Swan River First Nation) in Treaty Eight territory in northern Alberta. He has had creative worked published in Contemporary Verse 2, Prairie Fire, PRISM international and Arc Poetry. His first children’s book, Awâsis and the World-famous Bannock, was published through Highwater Press in 2018, and was nominated for several awards. Hunt is an assistant professor of Indigenous literatures at the University of British Columbia.

Rob Taylor is the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). His fourth poetry collection, Strangers, was published this month by Biblioasis. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.