The following interview is part four of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2021. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Manitoba

I found Black people between groves of wheat

drove hours along open road back to Winnipeg

heard whispers in the topography

Ta-Nehisi said I could go anywhere

he told me in two hundred pages that Black folks could travel

said seeing the world is not a luxury

reserved for white men

we do travel though

some of us are still

on ships

Reprinted with permission from Burning Sugar (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020).

Rob Taylor: You grew up in London (the big one that people outside of Canada know about) and moved to Vancouver for university. It’s been a relatively short amount of time, then, in which you’ve established yourself in the political (Black Lives Matter Vancouver, Bakau Consulting) and literary (Burning Sugar) life of the city. Could you talk about coming to Vancouver and learning to navigate those particular worlds? What do you think made it possible for you to establish yourself so quickly?

Cicely Belle Blain: I came to Vancouver to attend UBC. I had never been to Vancouver or even Canada before so it was a pretty nerve wracking experience. Aside from the mountains and beaches, the main selling point was the Karen McKellin International Leader of Tomorrow Award that UBC offered me: a scholarship that makes it possible for international students who cannot afford the high tuition prices to attend.

I have always been someone who gets involved in a lot of things. As someone with ADHD, the academic side of things is really challenging, so from a young age I’ve thrown myself into extra-curricular activities, especially if they were centered around politics and social justice. In addition, coming from a family of activists and change makers, helped me feel really primed and equipped to jump into activism, no matter the city.

I think my ability to grow my business, literary career and activism work is a combination of some of the privileges I hold as a light skinned, educated, British person and also the fearlessness I was taught by my grandmother and mum. I have always been instilled with the tools and confidence to stand up for myself and go for every opportunity.

RT: What major roadblocks stood in your way?

CBB: A lot of the road blocks I have experienced are tied to my race, gender and age. Especially in starting my business, I felt so many doors were closed to me because I did not have the intergenerational wealth and business acumen to understand all the complexities of running a business. Especially in the beginning, I felt clients looked down on me and undervalued my intelligence and knowledge.

RT: In “Hollywood, Florida” you write of “cross-Atlantic love” and it feels possible that you are speaking both of your own cross-Atlantic life and the Atlantic-spanning triangular slave trade. Indeed, in the first section of the book, “Place,” you travel in and around Europe, West Africa, and North America—all homes to either yourself or members of your extended family.

I’m obviously not equating the two “triangles”, but are there ways in which your travels caused you to think about the slave trade, and its ongoing legacy, in different ways than you would have if you’d stayed put in London?

CBB: Yes, definitely. Moving to North America and the opportunities I have had to travel have really exposed to me the unending and global nature of anti-Blackness. It has allowed me to connect the dots between my experiences growing up in London, the histories of colonialism and slavery, (which didn’t necessarily happen on British soil but were driven and enacted by Britain for centuries), and how my experience as a Black British person is a result of both the wealth generated by the Empire and the creation of anti-Blackness.

Moving to North America and the opportunities I have had to travel have really exposed to me the unending and global nature of anti-Blackness.

RT: Assuming the poems with place names as titles (like “Manitoba”) were written in those places, you traveled over half the planet in writing this book! At one point you mention that your browser has “thirty flight search tabs” and that you own “more bathing suits than underwear,” so I suspect travel has been central to your life and identity (you note at one point that travel “becomes my greatest escape”).

CBB: The ability to travel freely to so many places is definitely a huge privilege and something I understood to be a privilege from a very young age. My family made a concerted effort to provide us with the opportunity to travel, even at the sacrifice of other luxuries. I remember in ninth grade my teacher asked me why I didn’t choose geography as a subject to pursue and I replied that I felt like I already had front row seats to the best geographical education. I have always valued and appreciated my parents’ willingness to take risks—they’ve moved from the Netherlands to Italy to Kenya in the time I’ve lived in Canada.

RT: We’ve all had to live life differently since the onset of the pandemic, but I wonder if that isn’t particularly true for you, having lost your ability to travel. How has your time been during the pandemic? Has the requirement to stay in one place caused you to look at the world, or yourself, any differently?

CBB: Over the past year the value that travel holds has changed. It is no longer about exploration and fun and leisure, but about connecting or reconnecting with people, ancestors or culture. This has allowed me to view travel less from a Western perspective of ticking things off a bucket list and more as a sacred opportunity to find parts of me that are missing. I hope when the pandemic is over, I can dedicate my future travels to places like Gambia, Jamaica and other lands where my ancestry lies.

RT: In addition to your physical travels around the world, the poems in Burning Sugar also travel the internet in their explorations of racial injustice. “How many white people can say their death will end up on YouTube? Nestled between Ariana Grande and reruns of Ellen?” you write so powerfully in “Dear Philando Castille.” As an activist and organizer, what do you think the internet has enabled you to do that was unavailable to previous generations?

CBB: I think the unique experience of millennials is that we were the first to grow up almost entirely online. For older generations, it’s something that came along later, while Gen Z are getting to learn from our mistakes and successes. From as young as 6 or 7, I have pretty formative memories that revolve around the internet; by 10 I was using MSN to talk to friends (and strangers) online and so much of my self-exploration around my queerness, race and gender identity is thanks to the internet. While it’s not always safe, I think it is truly influential and I am so grateful to have grown up in this age (I often try to imagine what people did in the Spanish flu pandemic with no technology…).

RT: You mention that it’s “not always safe” on the internet (to say the least!). In what ways do you think he internet has made activism and organizing more difficult?

CBB: The main issue with the internet in my experience as an activist is the exposure to harm and violence from strangers. Many of the poems in Burning Sugar I wrote in 2017 after I left Vancouver for 6 months because of the hate and death threats I was receiving as a result of speaking up against police involvement in Pride.

RT: I’m so sorry that happened to you. You write about your experience at the Pride parade in the long poem “Toronto” (“We asked for recognition, safety, compassion, empathy and freedom. What we got was dismissal, hypervisibility, vilification and violence”). “Toronto” sits at the centre of your book and is, essentially, a short essay. This kind of genre-mixing is happening more frequently in Canadian poetry, perhaps most notably in your editor Vivek Shraya’s collection, even this page is white, which places a series of interviews at its centre.

Could you talk about the choice to put the essay (essay-poem?) at the middle of the book? More broadly, can you talk about what ways Shraya helped shape Burning Sugar (which she says “had all of the elements there by the time it reached me”)?

CBB: Working with Vivek was magical. As a young queer person of colour I was completely clueless on how to publish my work, and the opportunities and wisdom she provided were invaluable.

I knew that I wanted to explore different styles and genre. I really love all kinds of writing, and always have, and didn’t want to limit myself to just poems. I had intended to include more essays but they were the most time consuming, to play with the delicate balance of being beautiful and educational.

Working with Vivek was magical. As a young queer person of colour I was completely clueless on how to publish my work, and the opportunities and wisdom she provided were invaluable.

RT: “Toronto” explores the simultaneous desire to be at once visible and invisible—the desire to stand out (as queer, as black) and to blend into the crowd. Your jobs as a diversity consultant and a writer are very “public facing,” to say the least! How are you feeling now about that balance in your life? Has the nature of the balance you desire shifted at all since the time described in “Toronto”? Do you feel like you’re better able to achieve it?

CBB: I am currently feeling good about this balance. I think that has come from a boost in confidence over the past year; with the release and success of Burning Sugar, I can really feel the validation and affirmation that my work is important and people actually want to read it or hear me speak.

I have always struggled with impostor syndrome, especially after spending four years in a predominantly white academic institution. To achieve success in my writing and in my business feels like I am finally doing what I am good at, and it is appreciated and admired by others. This allows me to feel like less of a fraud when I post online or appear in media interviews. People are genuinely looking to me for my knowledge and expertise and that allows me to feel less anxious and awkward about it all. Although I am still a very awkward person—but most people who know me say I pull it off well.

RT: Ha! Well, you don’t show it in interviews, at least.

The second section of Burning Sugar, entitled “Art”, explores art exhibits by Black artists, and features letters (“epistolary poems,” if we’re being fancy) to the artists themselves. Your mother was a visual artist, and you note that you spent “many a weekend trawling the galleries of Europe”. How do you think visual and performance art has informed your writing? Your activism?

CBB: Art was definitely my first introduction to politics and activism. My mum, who is an artist and art teacher (she was even my art teacher in school), has always taught me that art has meaning and the power to make change. Almost all of the exhibitions mentioned in the book, I went with my mum and she has always provided spaces for critical thinking and exploration of creativity.

My mum, who is an artist and art teacher (she was even my art teacher in school), has always taught me that art has meaning and the power to make change.

RT: Your speaking to/with visual art by Black artists reminded me of Chantal Gibson’s wonderful collection, How She Read (you can read my interview with Gibson, from a previous iteration of this interview series, here). In addition to exploring the art, you both also focus on the overwhelmingly white spaces (the walls and the people) in which visual art is usually displayed. In your letter-poem “Dear Selina”, about UK performance artist Selina Thompson, you write:

Under the dim lights, I felt the vibrations of white people. Consumed by an intergenerational fascination with you/me/us. Enraged at their ancestors and counterparts—but never at themselves. Oblivious, mostly, to their complicity in the story you tell.

I also felt the Black bodies—some were my friends; others were people I wished I knew. Most were tense, leaning forward, metaphorical arms outstretched to hold you or be you or something else.

You obviously think a lot about space and audience: how they influence the art; how the various parts of an audience receive a work differently. A poetry book, like a gallery, has a lot of white space and is predominately consumed by white/straight “viewers,” though the reading of a poetry book is usually a private act, invisible to the poet. What were your thoughts about audience as you prepared Burning Sugar for publication? How do you think the unavoidable whiteness of a large portion of your audience shaped, and shapes, the book? Who do you imagine are the various members of your invisible “room” full of readers, and what do you hope they’re taking away from it?

CBB: I definitely had the potential whiteness of the audience in mind when writing, which is one thing I regret about the book. It is only very recently as people start to question and critique diversity and inclusion consulting or anti-racism training, that I realised a lot of anti-racism education is directed towards white people. We simplify big concepts, or sometimes even exploit our own trauma, to educate white people (I write about this here).

When I was writing Burning Sugar, I was doing this—writing for white people to understand me better, when really I wanted to be writing for myself and other Black queer people. I think I did achieve an equilibrium but I’m not sure.

We simplify big concepts, or sometimes even exploit our own trauma, to educate white people.

RT: The last section of Burning Water, “Child”, is about – surprise! – your childhood. The default assumption would be that one would put their poems about childhood at the beginning of their first book, not the end. Could you talk about that choice to close the book with it? Is it connected in any way to that equilibrium you were seeking?

CBB: I put “Child” at the end of the book because I felt like people had to do the hard work to get to the most intimate part! As a British person, I am not accustomed to being overly vulnerable with my emotions and even though I think there is so much power in emotional intimacy—with one another and with our readers—it does not come naturally! I felt it was important for people to first understand the larger systemic issues I was referencing and understand my adult experience, which is also a reflection of so many other Black queer people’s experiences. Then we could go down the rabbit hole into my past!

I also saw it as a reflection of how much access people have to me. As a “public figure” (I still cringe at the idea of this but I also have to recognize the responsibility and privilege that comes with my social position and capital), I constantly feel exposed, easily accessible to everyone at any time. This is extremely exhausting—people feel they can ask me anything, comment on everything I do and say and wear, even when it’s unsolicited. I felt with the this structuring of the book I was able to take back some control—assuming people read it in order—and invite people into my deepest memories and truths at my own pace.

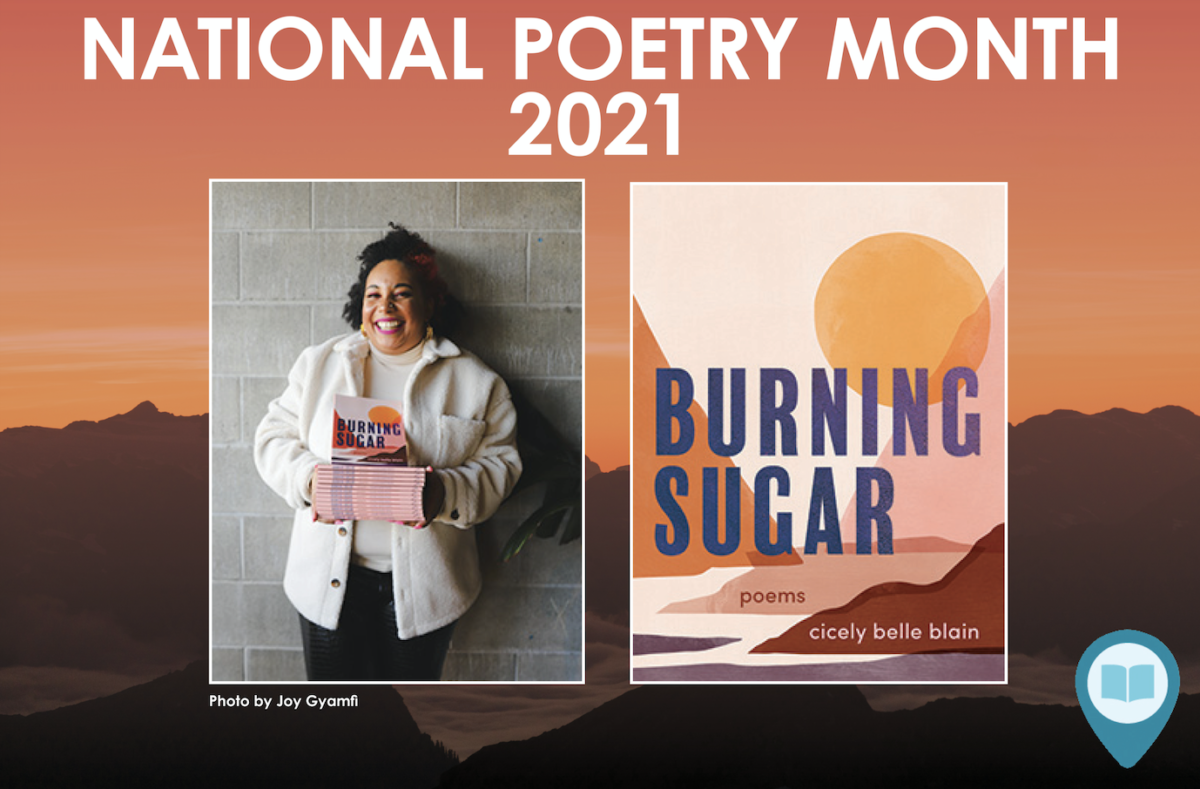

Cicely Belle Blain is a Black, multi-racial, queer writer, activist and CEO from London, UK. Cicely Belle is noted for founding Black Lives Matter Vancouver and subsequently being listed as one of Vancouver’s 50 most powerful people by Vancouver Magazine twice, BC Business’s 30 under 30, and one of Refinery29’s Powerhouses of 2020. They are now the CEO of Bakau Consulting, an anti-racism consulting company with over 1000 clients worldwide. Cicely Belle is also an instructor in Executive Leadership at Simon Fraser University and the Editorial Director of Ripple of Change Magazine. They are the author of Burning Sugar (Arsenal Pulp Press and VS Books) which was recently longlisted for the 2021 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award and the Pat Lowther Memorial Award.

Rob Taylor is the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). His fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸ was published this month by Biblioasis. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.