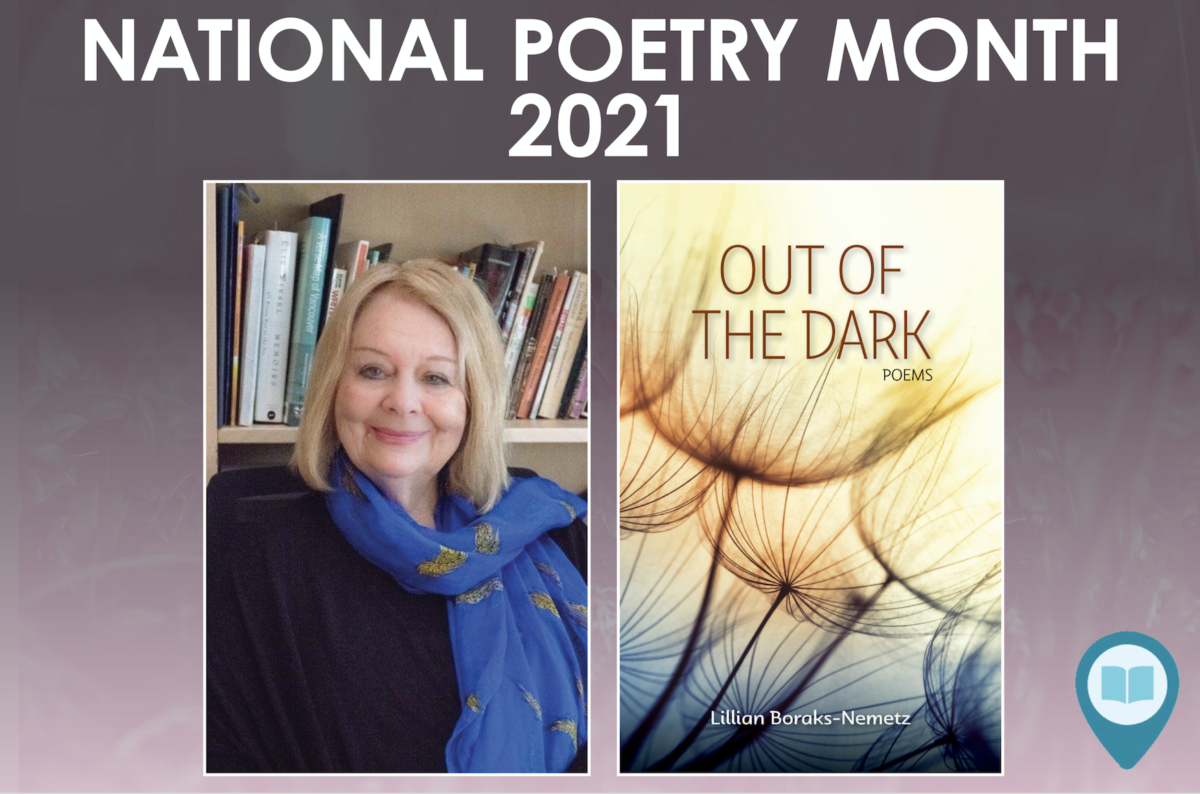

The following interview is part three of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2021. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Kiss in Nitobe Garden

How I kissed you that night

in the Japanese garden where we sat

framed in cherry blossom

and bamboo

even time was tangled

in its own twilight foliage

where only the leap of a fish

marked our separation

last night I went back to Nitobe

and there we were

framed in cherry blossom

and bamboo

and I remembered

the leap of a fish

and how I kissed you

that night

Reprinted with permission from Out of the Dark (Ronsdale Press, 2020).

Rob Taylor: As a child in WWII, you were incarcerated in the Warsaw Ghetto for eighteen months and survived the war in hiding in several Polish villages, before immigrating to Canada in 1947. You’ve written about this time in your life extensively in a variety of genres: the YA novel The Brown Suitcase (1994), the poetry collection Ghost Children (2000), the anthology Tapestry of Hope (2004), and the adult novel Mouth of Truth (2018), for instance. The first section of Out of the Dark is likewise devoted, in various ways, to memories of the Holocaust, but is then followed by poems about other parts of the world (including Vancouver), poems about gardens, about family, etc.

Could you talk a little about writing about your childhood, and the Holocaust, in Out of the Dark, and how it compares to your approach to the subjects in previous books? Have you noticed ways in which your writing on the subject has shifted from the last time you wrote about it in poetry, twenty years ago?

Lillian Boraks-Nemetz: When I first started writing about the Holocaust my voice came from an abyss, a place of indescribable pain inside me, and the sound would not be stilled.

I thought not only of myself but of all the other children of war, for they surely are the first most vulnerable, victimised by fear, hunger, loss, isolation and persecution. The feeling that society hates you for who you are (in my case, a Jew).

When I first started writing about the Holocaust my voice came from an abyss

A great injustice befell the Jews of Europe. We were a family who lived comfortably, who loved and played. My father was a successful lawyer and my mother a beautiful socialite. Soon it all fell apart when we lost our human rights, especially the right to live. This is what I write about both in prose and poetry. This is what I speak about to students and sometimes adults who understand less and are less compassionate that the young students.

The Warsaw ghetto, where my family and I were incarcerated and quarantined for typhus, was a treacherous place, and the wall that imprisoned us is still standing in my mind. Out of the Dark is the only book I’ve written that I’ve read many times after publication. It is my book of healing, a journey from the abyss to the world of life and love.

RT: Yes, I can sense that, and also that “the wall… is still standing in [your] mind.” In “Terezin, 1998” you write “why do we Jews keep returning?” and while that question can be asked of literal travel to the sites of the Holocaust (in Poland, Germany, etc.), it can also speak to this still-standing wall, and to the literary “returns” you keep making to the country on the page. Could you talk a little about your travels in adulthood to the region?

LBN: Terezin is in the Czech Republic, near Prague, where I attended one of the Holocaust Child conferences. It represented for me all camps, better or worse. But I did return to Poland frequently where I visited the Warsaw Ghetto grounds, a bit of the wall still standing. I visited Treblinka where my family was murdered, then Auschwitz. I brought all these images with me to put into stories and novels.

RT: The theme, and question, of “home” hangs over much of this book. Warsaw, Vancouver and Jerusalem are all presented as places to which you are in some way bound, and from which you are in other ways alienated (language, history, religion, etc.). You’ve lived in British Columbia for over seventy years, so I’m sure Vancouver must feel like “home” in most regards, but could you talk a little about what traveling to, and writing poems about, these three places did for your thinking about the ideas of “home” and “homeland”?

LBN: Immigrants who lose their homeland forever live in exile, even when they accept their adopted home as their own. I love and respect Canada, but my language was broken when, having written in Polish, I was forced to switch to English. So my writing is that of a late bloomer.

It’s here in Canada I was able to heal, in a society where peace prevailed. I am aware of Canadian parks, trees and flowers. I am aware of climate change. People only see me as a Holocaust Survivor and I resent that. They do not read my work as that of a writer.

RT: This leads us nicely to talking about parks: a central theme in Out of the Dark‘s second section is the garden, both as a physical space and an idea. In the book, we visit UBC’s Nitobe Garden and “Irina’s Garden in Southlands”, presumably just a little ways down the road, but also the Jardin de Luxembourg in Paris, among others.

Gardens are presented as places of both respite and creation, spaces for the ever-renewing (and possibly infinite) amidst life’s changes. Could you talk about the role of gardens in your life, and your creative process?

LBN: I love gardens. My first love was a Polish garden where sunflowers, which are my favorite, grew taller than me. It was in Poland, where I roamed forests and fields, that I learned the magic and beauty of nature.

My first garden was after all the primal garden, the garden of Eden. A place of peace and beauty, also of deceit and betrayal, like the world.

Here in Canada I saw those images in translation at first, then they became authentic. As I walk along the streets I do not miss a little park, flowers growing on the side, and magnificent trees in all their season. Finery… even barren winter trees stretch out their branches in beautiful configurations….

My first garden was after all the primal garden, the garden of Eden. A place of peace and beauty, also of deceit and betrayal, like the world.

RT: This idea of a “place of peace,” a place of respite amidst the world’s betrayals, runs through many of your poems. In “Old-Fashioned” you mention that meditating in a garden shelters you “from the wind / and modern cacophonies”. Often enough, though, it’s those very cacophonies that you’re writing about! Does the shelter – manifested in gardens, or meditation, or otherwise – give you the space and rest you need to go back out in “the wind,” so to speak?

LBN: I carry within me an inner garden, so even in a trench I can envision the garden’s beauty and its influence on my writing. I don’t have to go there physically. James Joyce said that he finds what he needs in the “smithy of his soul.”

RT: You mentioned earlier that moving to Canada allowed you to heal from the “cacophony” of your childhood. In a sense, would you say that Vancouver has acted as a garden in your larger life, just as the gardens within Vancouver have granted you shelter from the larger city?

LBN: I don’t look at my Polish experience as a cacophony. I look at it as partly my childhood discoveries of life’s nature and attributes, and partly as an apocalyptic garden of WWII. As in the Garden of Eden from which we were all exiled.

Canada is the real world where I came to heal. The cacophony persists in a social world, where people are selfish , self-oriented, asleep and materialistic. I see this in the way some of my books are perceived and read… their eyes lacking inner vision.

RT: Your poems eschew punctuation, with the exception of the occasional question or exclamation mark. Similarly, with the exception of proper names (and the opening word of every poem), they lack capitalization. All of this prioritizes the importance of enjambment – your strategic breaking of the line – to communicate pauses, breaths, and often the logic of sentences. Could you talk a bit about your decisions to minimize capitalization and punctuation, and the role of enjambment in your poetry?

LBN: I use spaces instead of commas. I don’t use periods at the ends of lines. I hate punctuation, but my publisher, who had a hard time with the rhythm of my poetry, managed to sneak them into certain places unnecessarily. I tend to sacrifice English constructions for my own rhythm and content.

RT: You’ve translated the poetry of Wacław Iwaniuk and Andrzej Busza, Polish poets who, like yourself, immigrated to Canada soon after the war. Could you talk a little about how translation and, more broadly, Polish poetry and the Polish language, have influenced your own writing style?

LBN: Translation influenced my English writing hugely. J. Michael Yates, an American poet teaching a creative writing course at UBC, noticed that I had a knack for translation and encouraged me. I was also encouraged by a British Poet at UBC , Michael Bullock, also known worldwide for his German translations.

I come from a broken language. I wrote in Polish as a little girl, then I was told when we came here that my past did not exist, only my English future. When I saw a Polish poem translated into English, I saw the possibility of my own writing. Here no one understood my harsh imagery, nor anything else I wrote about, and my work was rejected. A Polish scholar and a German poet told me once that when two animals fight with each other a third emerges. That was my version of English poetry.

I come from a broken language. I wrote in Polish as a little girl, then I was told when we came here that my past did not exist, only my English future. When I saw a Polish poem translated into English, I saw the possibility of my own writing.

RT: In your acknowledgments, you thank George and Angela McWhirter, and also Ronald Hatch (Ronsdale’s publisher), for their support of the book. You’ve had long relationships with all three, having studied and worked with George in UBC’s Creative Writing program, and having now published three books with Ronsdale over a 20 year span. Could you talk a little about the role these three people have played in bringing you to the place of publishing Out of the Dark?

LBN: The McWhirters are great. They have always been hospitable and good natured and non-judgmental. Whenever I needed help, George was always there, and Angela too. I am grateful for their help.

I love and respect Ronald Hatch. He has done so much for Canadian poetry including a few immigrants like myself. He should be applauded and thanked for his contribution to Canadian literature.

Lillian Boraks-Nemetz was born in Warsaw, Poland, where she survived the Holocaust as a child, escaped the Warsaw Ghetto and lived in Polish villages under a false identity. She has a Master’s Degree in Comparative Literature and teaches Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia’s Writing Centre. She is the author of numerous books, including Ghost Children, a collection of poetry, The Old Brown Suitcase, a young adult novel, and her recent adult novel Mouth of Truth: Buried Secrets.

Rob Taylor is the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). His fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸ will be published this month by Biblioasis. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.

One reply on “A Third Animal Emerges: An Interview with Lillian Boraks-Nemetz”

Lilly, Rob Taylor in this interview exposes some angles that I had not heard from you before, which makes it interesting.

Out of the dark is a true success, in my view your best work.

Love from Lou