The following interview is part seven of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. It’s also part two of our interview with Yvonne Blomer (you can read part one here). New interviews will be posted everyone Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2020. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Water – George Szirtes

The hard beautiful rules of water are these:

That it shall rise with displacement as a man

does not, nor his family. That it shall have no plan

or subterfuge. That in the cold, it shall freeze;

in the heat, turn to steam. That it shall carry disease

and bright brilliant fish in river and ocean.

That it shall roar or meander through metropolitan

districts whilst reflecting skies, buildings and trees.

And it shall clean and refresh us even as we slave

over stone tubs or cower in a shelter or run

into the arms of a loved one in some desperate quarter

where the rats too are running. That it shall have

dominion. That it shall arch its back in the sun

only according to the hard rules of water.

Reprinted with permission from Sweet Water: Poems for the Watershed, ed. Yvonne Blomer (Caitlin Press, 2020).

Rob Taylor: I know this is an extremely cruel question, but could you talk about one poem from the anthology that jumps out to you as representing something important that’s happening in the book?

Yvonne Blomer: Ugh. It’s like asking me which kid I love best… I only have one kid.

Ha! It should be easy then!

Ok, I will speak of George Szirtes’ poem, “Water,” not necessarily as a favourite but as a representational poem. It begins the book, and first appears in his 2004 collection Reel, which won the T.S. Eliot Prize. I was his student at UEA in Norwich, UK and my memory of the award night is conflated with the Boxing Day tsunami that caused so much destruction and cost the lives of over 200,000 people. A group of us students travelled to the Eliot awards in London and George read that poem. I was utterly captured in a moment where I was mourning the human loss and devastation from the tsunami, one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. Its reverberations were felt on the beaches of Malaysia and Thailand, two countries I had cycled through years earlier. The poem captured the awe and power of water in a time when we were mourning the effects of that power. I wanted George’s poem in the book for this very reason – to remind us that we are not in control, and that for us to continue to believe we are is beyond egotistical and arrogant. Yet the poem contains in it such simplicity, and beauty in that moment of water “arching its back,” caught by the poet’s eye. The poem itself may not have a political will, but it contains political reverberation, and for me that is essential.

“The poem itself may not have a political will, but it contains political reverberation, and for me that is essential.”

For many of the poems in Sweet Water I can hear the poet’s voices in my head. Or I can recall working with the poets: one a grade 12 student who tweaked her piece with me; others I worked with to help focus and refine their already strong poems; some pieces I asked for specifically because I wanted cities in the book, and boreal forest, fires, and poisons. There is a thread of feminist poems and that is important to me as a female writer and a feminist, so perhaps the other poem I’ll highlight is…

No, it’s too hard. I have flipped through, I have landed and reread. All I can say is read the book. Write in the margins, argue with the poems, write counter poems and response poems. I love them all.

Your answer re: Szirtes’ poem was lovely. Still, I promise not to torture you like that again! Let’s stick to talking about anthologies writ large.

We’re in the middle of a “boom time” for anthologies published by BC presses, including Arsenal Pulp’s Hustling Verse, Harbour’s Beyond Forgetting, Anvil’s The Revolving City and many more. No one is championing the anthology more, though, than Caitlin Press, which in recent years has put out BIG, Rising Tides, Body & Soul, Swelling with Pride, Love Me True, Making Room, Boobs and In Fine Form. Prior to the “Waterways Trilogy,” you co-edited the anthology Poems for Planet Earth, so you’re in your own anthology “boom time,” too! What do you love about anthologies, and what role do you think they play in our larger literary culture?

It’s interesting because often anthologies do not sell as well, yet the desire to bring voices together is compelling. Literary journals are a kind of anthology, too. I think writers, and particularly poets, are lonely creatures who work in their small spaces talking to themselves (I certainly do…), so when a book can pull in many voices and let them talk to each other, I think a kind of magic happens.

“As with how we’ve come together at this particular time in world history to protect ourselves from a virus, we must come together and communicate for the ecology of the planet, too.”

Working with the 110 poets here has been a phenomenal experience in community building outside of the conversations held by the actual poems. As with how we’ve come together at this particular time in world history to protect ourselves from a virus, we must come together and communicate for the ecology of the planet, too.

Zach Wells recently posted on Facebook that he received his copy and that he has an old poem in the book. Poetry does not care how old it is. Water is ancient. Conversations that writers began over two thousand years ago, continue today.

In anthologies like Refugium and Sweet Water varied voices and perspectives bounce off each other. Just now I was trying to choose a favourite and I came to page 162-163 with Elee Kraljii Gardiner’s poem “Exorcise” on the left and Aaron Kreuter’s “Hydrophobia” on the right. Elee’s is about running in a forest, a watershed forest. It is a feminist poem: the female voice will not speak to men because rage builds in her as she runs, rage at all the fears and frustrations caused by bad men, by arrogance and can-do attitudes. Aaron’s poem comes from an utterly different space and place except for the fear: in his poem it is fear of water and all that lurks within it. How is Aaron’s poem read differently after Elee’s? What if I flip from Brent Raycroft’s “Blue Roof” to Aaron’s, how might that alter how I read his, or Brent’s or any other poem before or after? This is an anthology. Shifts in tone and voice awaken the reader, language builds, mood deepens or completely turns around.

I love that idea of each poem rearranging the next on some quasi-molecular level (though I, too, am a serial anthologist, so perhaps I’m biased). But as a fellow serial anthologist, I can appreciate how much work goes into making a book like this. Many people don’t have a sense of it, including those inside our industry (a small example: the Canada Council’s Public Lending Rights program only credits anthologists as the creators of their anthologies if their introductions are over 10 pages long – as if the introductions were the most demanding part!). How do you think the work involved in pulling together an anthology compares to the work of writing and assembling your own poetry collection, both in the effort involved and the nature of that effort?

Yes, it is a shame that more funds can’t be provided for editors of anthologies and that Public Lending Rights doesn’t acknowledge the work in curating a book in the way an anthology editor does. It is a lot of work and it takes time. I recently helped with a chapbook with nine poets and I jokingly called myself Poet Wrangler. Perhaps the Canada Council should have a special grant for Wranglers in the Literary Field to acknowledge this work. I think publishers also could use more support for anthologies, as from the publisher’s perspective, an anthology is a whole lot of writers from whom contracts must be gathered and cheques or books sent out. They add a fleet of people to track, that individual books do not.

“I recently helped with a chapbook with nine poets and I jokingly called myself Poet Wrangler.”

There are so many more people involved in an anthology and the pressure on the editor has a unique texture to it. The editor carries each poem and poet’s words, and is ultimately responsible for the shape of those words being set in an object, a book. The selection process can be difficult. I know many of those who submitted, making the rejections even harder. There is an immense obligation to do the work and get on with it. Sweet Water took longer than I anticipated. With my own books, of course, there is no pressure to ever finish and I think that adds an element to the process, you have to keep yourself on track rather than keeping other people on track or being responsible to others to stay on track.

Also, I miss a lot of errors or blips in my own work but I am good at seeing them in other people’s, which defines the role of editor and shows why it is so important.

In addition to your work as an anthologist, you organized poets as the long-time coordinator of the Planet Earth Poetry reading series in Victoria. In what ways did that work prepare you for your work as an anthologist? What do you see as the main differences between these two curatorial processes (beyond the obvious ones!)?

I think I would not have become an editor without Planet Earth Poetry, where in a sense I was a curator, or “impresario” as Patrick Lane always called me. In 2000 my husband and I, newly returned from Japan, decided to go out to a poetry event we’d seen in Monday Magazine called “Mocambo Poetry.” From then on, I was hooked into a community created by Wendy Morton and others. That community shaped me into a writer who doesn’t just write her own work, but who champions other writers and causes. I got to know a lot of poets across the country from bringing them to Victoria and that gave me a lot of people to invite to submit to Poems for Planet Earth, my first anthology. Cynthia Woodman Kerkham came on board to help with selection and was a great co-editor and continues to be a great friend. I love the Neil Astley anthology Staying Alive. Cynthia and I decided to organized PEP’s anthology in a similar way, but we also wanted to capture a night at Planet Earth Poetry. By that I mean there are often 12-14 open mic-ers and two featured readers and on any wild night the poems create connections, like tiny roots weaving through the room: some microscopic, some large enough to hold a Garry Oak.

My faith in my ability to put together a book came from my experience in assembling the series for for nigh on ten years, both from getting to know so many poets from across Canada and the more mundane skills of organizing a whole year, filling in grant application, doing the scheduling, communicating with a lot of people over several months, etc. All those skills have helped me in numerous ways beyond building anthologies.

In addition to the poems, this book teems with epigraphs and quotes! Many of them are drawn from scientific sources or writers who have focused on water, such as Maude Barlow (author of many books on the future of water, including Blue Gold and the recent Whose Water Is It, Anyway?). Beyond the contributors, what books or authors helped you frame your thinking about water and the anthology’s approach to it?

Because of my concern for the environment, for water systems and species that rely on them, I have been reading and pondering both ocean and fresh water for a while. For Refugium, one book in particular was Dancing at the Dead Sea by Alanna Mitchell. The Pacific Ocean, vast as it is, is a single entity, but oceans and seas cover most of the planet. For Sweet Water, I spent time deepening my understanding of how our planet’s essential water systems work. It is important to have a broad understanding in order to not have that awful Imposter Feeling that can come with new projects. Despite the fact that I am not a scientist, through editing these books I have a much better understanding of water and how it moves on and below the earth.

As for other books or authors who helped me frame my thinking: Rita Wong, of course. The Council of Canadians website as well as papers published by the UN on climate and water. Jan Zwicky and Robert Bringhurst’s book Learning to Die: Wisdom in the Age of Climate Crisis is still within reach and was a kind of essential text. I read a lot of poets. I read a lot of Seamus Heaney. I read at the Whistler Writers Festival and Maude Barlow was a speaker. She knew her subject so well and devastated me again and in multiple ways about water. After having her sign my book, I bravely gave her a postcard for Sweet Water and a copy of Refugium, then emailed her to ask for a blurb.

Speaking of voices you brought into the book, Philip Kevin Paul opens Sweet Water with an excellent foreword. In it he notes that when we visit bodies of water we can come away “touched for a time, and held in the shape that we might truly accept, for once, ourselves.” Beyond the immediate politics, how has editing these anthologies influenced your thinking about your body (surrounded by water and composed more of water than anything else) and your wider self?

It’s a great honour to have Kevin’s introduction in the book. He and I worked together in a magical state of close listening, emails and phone calls. I so appreciate his voice and his presence in the world.

“During my pregnancy, I became a swimming pool with eight extra litres of water that I imagined my son swimming in.”

For my own part, I really don’t want to touch anything on this planet anymore. I don’t want to make a path or mark with a footprint. I cringe at our impact. With COVID-19 I’ve felt a shift in myself, that maybe after this, rather than a return, there will be some recovery for the planet, and I won’t feel ashamed to dip my feet in a lake. While I revel in the beauty of humanity, I worry humans are a poison. During my pregnancy, I became a swimming pool with eight extra litres of water that I imagined my son swimming in. When I think of that, I understand that we too are watershed. If my back garden is part of the natural world because there are plants and birds and things made of wood, is a fire hydrant? How about a well? Or a slough dug for water drainage? I want to better understand how humans can be part of the natural world, rather than constantly butting our heads and machines against it.

I think the first ghazal in Elegies for Earth (Leaf Press, 2017) speaks to this:

Ghazal 1

In the middle of the end you begin to make lists. Again.

Sea stars. Coral. Bull kelp. The American Avocet.

On a bicycle riding uphill among trees, lost or close to, you plot

a route to coast. Light through leaves. Morse code that could be expressive.

Something about speed and time. Loss, or tread’s rumble on road.

You tire of marring the earth. Rust caught in the scent of spring. Rot.

Somewhere, substance, a lifeform to grip. The moon evaporates with the tide.

Rain and you, thirsty for the green dark.

If the crow steals the murder weapon? If the bicycle is no longer enough?

At the top of your lungs sing … dew on the hummingbird’s wing.

Can you tell us anything about book number three of the trilogy?

Yes. We are all recovering, and holding our places for the future when the machine of humans revs back into action (May we learn from this how to protect what is precious!), but when that happens the book will focus on the Atlantic Ocean (may cruise ships be forever in a state of demise) and the flora and fauna of it.

***

Read part one of this interview here.

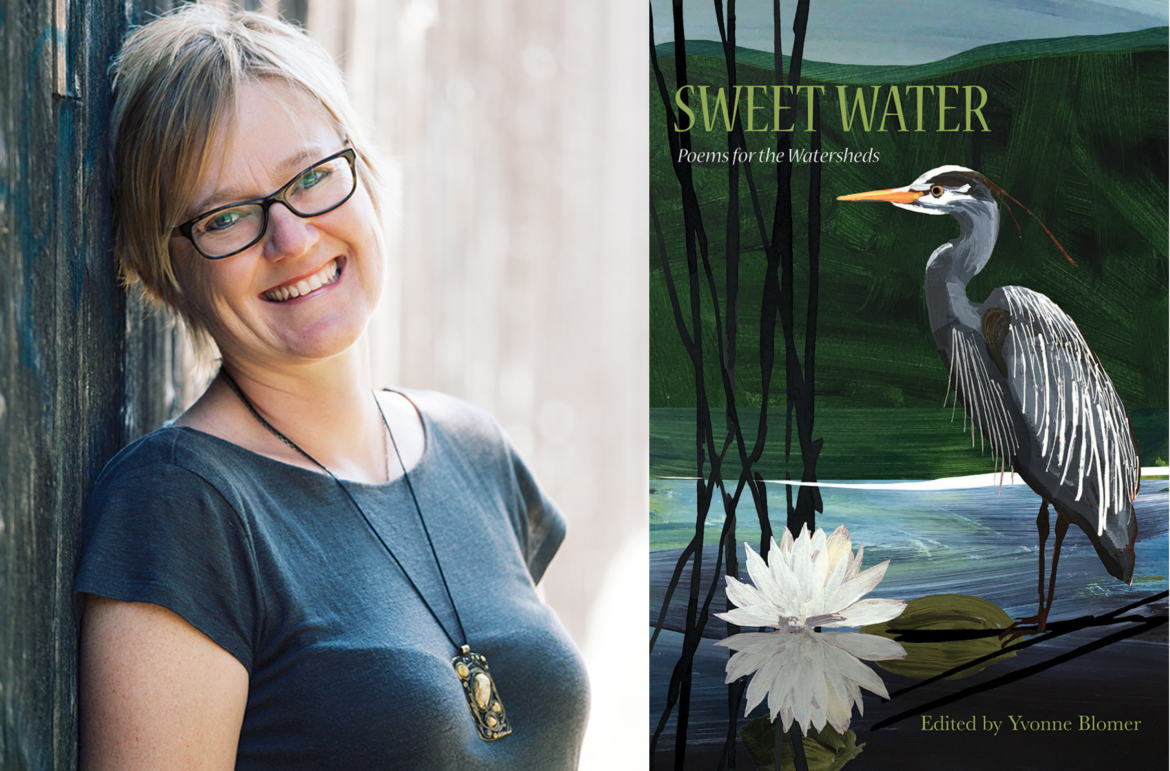

Yvonne Blomer is the author of a travel memoir Sugar Ride: Cycling from Hanoi to Kuala Lumpur, and three books of poetry, as well as an editor, teacher and mentor in poetry and memoir. She served as the city of Victoria poet laureate from 2015-2018. In 2018 Yvonne was the Artist-in-Residence at the Robert Bateman Centre and created Ravine, Mouse, a Bird’s Beak, a chapbook of ekphrastic ecological poetry in response to Bateman’s art. In 2017 Yvonne edited the anthology Refugium: Poems for the Pacific (Caitlin Press) with poets responding to their connection to the Pacific from the west coast of North America, and as far away as Japan and New Zealand. Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds is the second in a trilogy of water-based poetry anthologies coming out with Caitlin Press. She lives, works and raises her family on the traditional territories of the WSÁNEĆ (Saanich), Lkwungen (Songhees), Wyomilth (Esquimalt) peoples of the Coast Salish Nation. She gives thanks for the privilege of water.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.

Read more 2020 National Poetry Month features here.