The following interview is part six of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted everyone Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2020. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Sounds A River Makes – Claire Caldwell

Gas leak, ventilator, bear clicking its teeth.

Twelve hundred caribou hooves on frost.

Lips around bottle, bottle clinking

on bar. Rattling aspen, dusky grouse,

sheets drying outside. Grandmas

stuffing envelopes in a high school gym.

Sex in a sleeping bag, house on fire.

A children’s choir after one kid

has fainted.

Reprinted with permission from Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds, ed. Yvonne Blomer (Caitlin Press, 2020).

Rob Taylor: Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds is part two in your “Waterways Trilogy” of poetry anthologies on our oceans, lakes, rivers and drinking water. “Trilogies” are usually reserved for blockbuster movie franchises, not poetry anthologies! Could you talk about coming up with the idea and pitching it to Vici Johnstone at Caitlin Press? Did it take much convincing to get her on board with such an ambitious project?

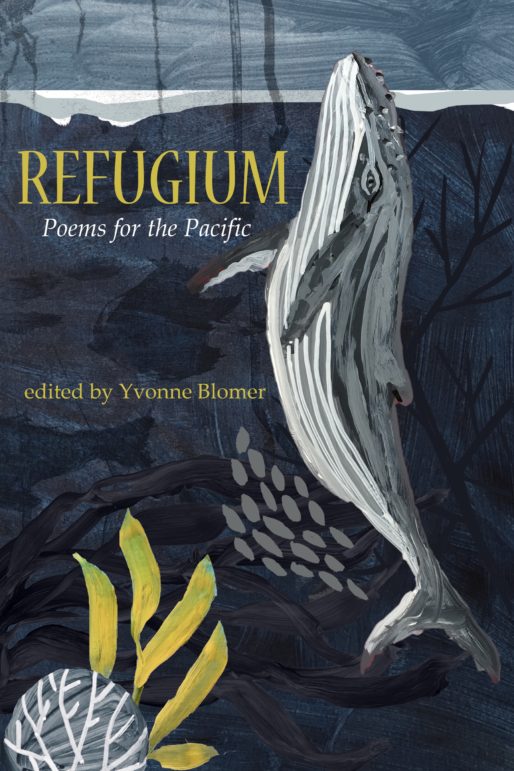

It’s true, we don’t often think of poetry anthologies or poetry books as genres that conform to trilogies or series, and this series didn’t begin as such. It began as a single book, Refugium: Poems for the Pacific.

Much of what has led me here, to editing a second, and a third in the future, began with the first book and my sense of responsibility and curiosity as to how to define, for myself, the political and public role of Poet Laureate. I had decided, when I became Victoria’s Poet Laureate in 2015, that my focus would be on the Pacific Ocean. I made a list of possible publishers and started with Caitlin Press. Vici said yes right away. Vici was superb to work with and the book(s) fit into Caitlin Presses publishing mandate.

Joe Denham is in Refugium and he and I were discussing which of his poems to include (I chose his octopus poem “Gutting” because it is so very horrific) and he put forward the idea that his poetry books are a trilogy of books on a similar theme. Some of the poets in Refugium wondered if I’d do another, and with his trilogy in my mind, I broached the subject with Vici. We planned out the timeline and began to move forward on book two: Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds.

Refugium was and continues to be an important book. I find it incredibly difficult to assess the success of a book beyond sales, but I feel like a lot of good conversations have been borne from Refugium. Despite the setbacks, and necessary setbacks at that due to our current pandemic and safety measures, I feel Sweet Water can be important too.

Absolutely! Because of the pandemic’s distancing measures, I feel like there’s increasing value in phyiscal books that connect writers and readers on subjects that are vital to our existence. My hope is that this pandemic will shift how we think about all the essential elements of life that we take for granted. On that: though you wrote the introduction to Sweet Water pre-COVID-19, you note there that a shift in how we talk about climate change and the environment was already underway.

You write that in the three years since the publication of Refugium, the defeat of the Conservative government has allowed scientists to speak more freely and vocal young activists (like Autumn Peltier and Greta Thunberg) have helped change the national conversation. As you put it, “while Refugium may have been just ahead of its time, Sweet Water arrives midstream.”

What effect did being “midstream” have on both the volume and the nature of the submissions themselves? What effect did it have on what you wanted to accomplish with the book?

This is a good question. It is also large and perhaps hard to measure how coming in at the height, perhaps, of the climate crisis and our awareness of the water crisis will affect the book. Probably there are still people not thinking about water conservation at all. So perhaps to them, if they flip open the book, drawn to it by the cover no doubt, they may pause. A moment’s pause can create an immense change in a person, and it’s those pauses that poetry tries to grasp and perhaps seize.

“I’m curious to know where the environment stands during the COVID-19 outbreak and where it will stand afterward.”

I’m not sure that our stage in the climate crisis influenced my selection process, though it may have influenced the poets in what they wrote and how they approached the subjects. In both books I hoped to remain very open to what I read, and in this one I was open to varying ways of contemplating and considering “watershed.” I didn’t go in with a firm plan, even after I’d edited the first book, but with my mind and my reading tuned to water and watersheds and definitions of those things. Tuned to definitions of the natural world. I wanted the human to be natural as well. I wanted a broad scope throughout the book, with poems that were specific. I felt less sure of the concept of watershed myself, compared to the Pacific Ocean, though both of these entities are vast and uncontainable.

I do wonder, now, today in early April, how our current state will affect the environmental movement. I delight in noting recovery in the ocean and its mammals and fish from a reduction in human movement. I delight in clearing skies and a reduction in emissions. I noticed that when coffee shops could no longer use reusable cups – which I agree with – I couldn’t bring myself to get takeout coffee. We can’t use reusable shopping bags now, so how is that for plastic reduction in the world? We are washing our hands more, our clothes, no doubt, too. How is that for water conservation? I’m curious to know where the environment stands during the COVID-19 outbreak and where it will stand afterward.

I love the mix of big, abstract, thoughts and simple tangible realities in that response. Our considerations of the environment/climate change so often boomerang between the two. In your introduction, you quote Simone Weil: “The poet produces the beautiful by fixing attention on something real.” What role does beauty play in an anthology with explicitly political/abstract goals? In picking poems, did you ever feel the need to prioritize politics over beauty, or vice-versa?

In picking the poems I tried to prioritize poetry over lines of words and images. I worry as I write this that I sound snobbish or close-minded or closed to experimentation, but I hope I am not. I am open to play with language and line, to awkwardness and strangeness, but I feel that poetry is a specific form of writing and that some of the pieces that came in faltered either by being overwhelmed by the subject or by being too didactic, which can lead to a piece of writing that is perhaps not a poem and is also too overtly political. I think writing poems is hard and writing about a specific subject is perhaps particularly difficult. I think the poet and the poem can drown in the details. The artistry, and craft, can get lost. Much of it comes down to creating a poem that hones in on something specific rather than trying to capture the whole idea of watershed in a few lines. The Weil quote, for me, the heart of that quote, is “fixing attention” and through attention, finding the one moment or small part of the larger, to focus the eye and the poem.

On this theme of “fixing attention,” your most recent poetry collection, As If a Raven, has its attention fixed on birds, not just writ large, but in their particulars. It dwells in birds and goes to lengths to name them (the first poem of the book, for instance, lists seven different varieties of cormorants, from Pelagic to Olivaceous). That book opens with a quote from Tim Lilburn which reads, in part “The Western religious regard for the world often seems to amount to an attention to the world that thrusts the world aside to grasp the presumed light within.”

Confronting that idea — that in the West we reach past, instead of seeing, what’s in front of us – seems central to this trilogy of anthologies, which asks us over and over to look closely at the natural world. And yet, at the same time, isn’t poetry always, in some way, a grasping for the presumed light within? Are there limits to how much poetry can bring us into attention toward the natural world? If so, what role do you hope for these anthologies to play, knowing their limitations?

I guess the dream of poetry is that it catches a reader and that reader’s pulse slows a bit and they enter the poem and see the thing in the poem. A book with 110 voices maybe has higher odds (do we play in odds with poetry?) of catching a reader because the poems come from so many places and voices. Something will stick. The idea from Lilburn of “thrusting the world aside to grasp the presumed light within” is very much an issue with poetry. What is the light (or meaning, in a metaphorical sense) to that which I’m seeing before me? Why can’t we just see the river and let the river be? This is a hard thing. I think in Sweet Water we have a gathering of multiple ways of seeing water, and some are metaphorical and so see the light below the water, if I read Lilburn’s quote in this way. Some see the water for what it is, in all its essential glory.

After all that time with the birds of As If a Raven, why did you take on water next, and why (beyond simply being Victoria’s Poet Laureate and needing a project) did you take it on in anthologies and not a themed book of your own poetry?

One of the great things about an anthology is there is no underlying cringe or worry about the poems, once they are selected and fretted over. There’s no fear of being too proud. I’m all in. With my own work, I’m more trepidatious. As Poet Laureate I took the notion of bringing poetry to unusual places and bringing more people to more poetry very seriously. It was the water on which I floated, so the anthology came out of that responsibility. I was surprised by the responsibility I felt as a poet in a political role when I became Poet Laureate, so Refugium seemed to fulfill that responsibility and it fit into my own desires and beliefs and frustrations for the Pacific Ocean.

“Why can’t we just see the river and let the river be?”

I am also working on my own book of environmental poems. A selection won the Leaf Press 2017 Overleaf Chapbook Manuscript Competition and was published as the chapbook Elegies for Earth. But these days there are many poetry books focused on the environment, so I’m not sure that’s something I absolutely need to do. I like the anthologies for their many ways of seeing and speaking on water, rather than my one voice.

Birds, both of salt and fresh water, are incredibly endangered. As if a Raven began as my Master’s thesis and as I was writing and researching I often had the passing thought of a second book — there is so much in the mythology of birds, in how we use and abuse them to find our own meanings — which of course is Lilburn’s light behind/within the idea of bird, rather than seeing the real bird. I think by the end I felt guilty and weary of not seeing birds for the wild creatures they are when my whole intent had been to question their use in mythology. I too created metaphors and myths out of them, rather than trying to truly see them as they are. I do still write of birds, though, and their imperilled existence due to our egotistical ways.

***

Click here to read part two of this interview.

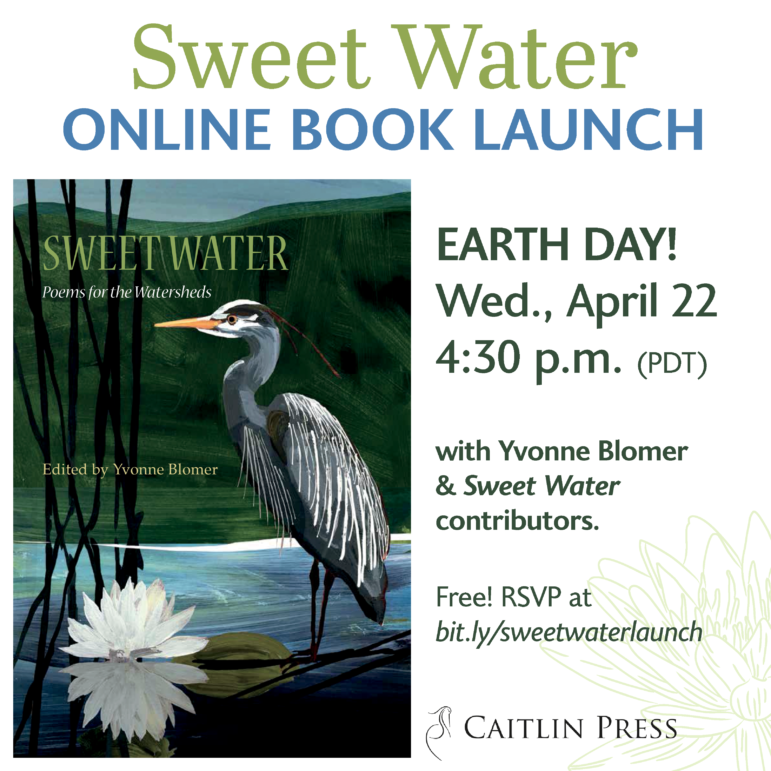

Join Yvonne Blomer at the launch of Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds tomorrow, April 22 at 4:30 p.m. RSVP at bit.ly/sweetwaterlaunch

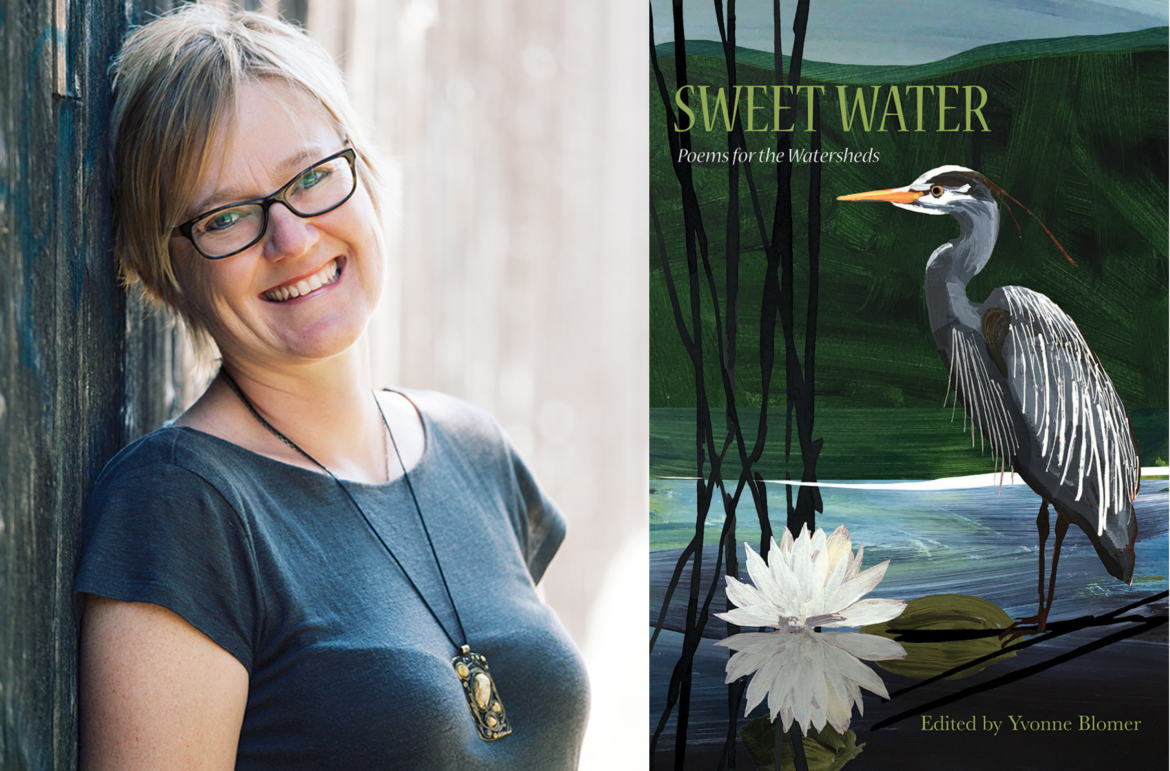

Yvonne Blomer is the author of a travel memoir Sugar Ride: Cycling from Hanoi to Kuala Lumpur, and three books of poetry, as well as an editor, teacher and mentor in poetry and memoir. She served as the city of Victoria poet laureate from 2015-2018. In 2018 Yvonne was the Artist-in-Residence at the Robert Bateman Centre and created Ravine, Mouse, a Bird’s Beak, a chapbook of ekphrastic ecological poetry in response to Bateman’s art. In 2017 Yvonne edited the anthology Refugium: Poems for the Pacific (Caitlin Press) with poets responding to their connection to the Pacific from the west coast of North America, and as far away as Japan and New Zealand. Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds is the second in a trilogy of water-based poetry anthologies coming out with Caitlin Press. She lives, works and raises her family on the traditional territories of the WSÁNEĆ (Saanich), Lkwungen (Songhees), Wyomilth (Esquimalt) peoples of the Coast Salish Nation. She gives thanks for the privilege of water.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.

Read more 2020 National Poetry Month features here.