The following interview is part five of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2020. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Self-Image So Far

Like the allegory

Of the cave but a girl

Seeing only her shadow

On the bottom

Of the outdoor pool

Never the pattern of light

Rippling across her back.

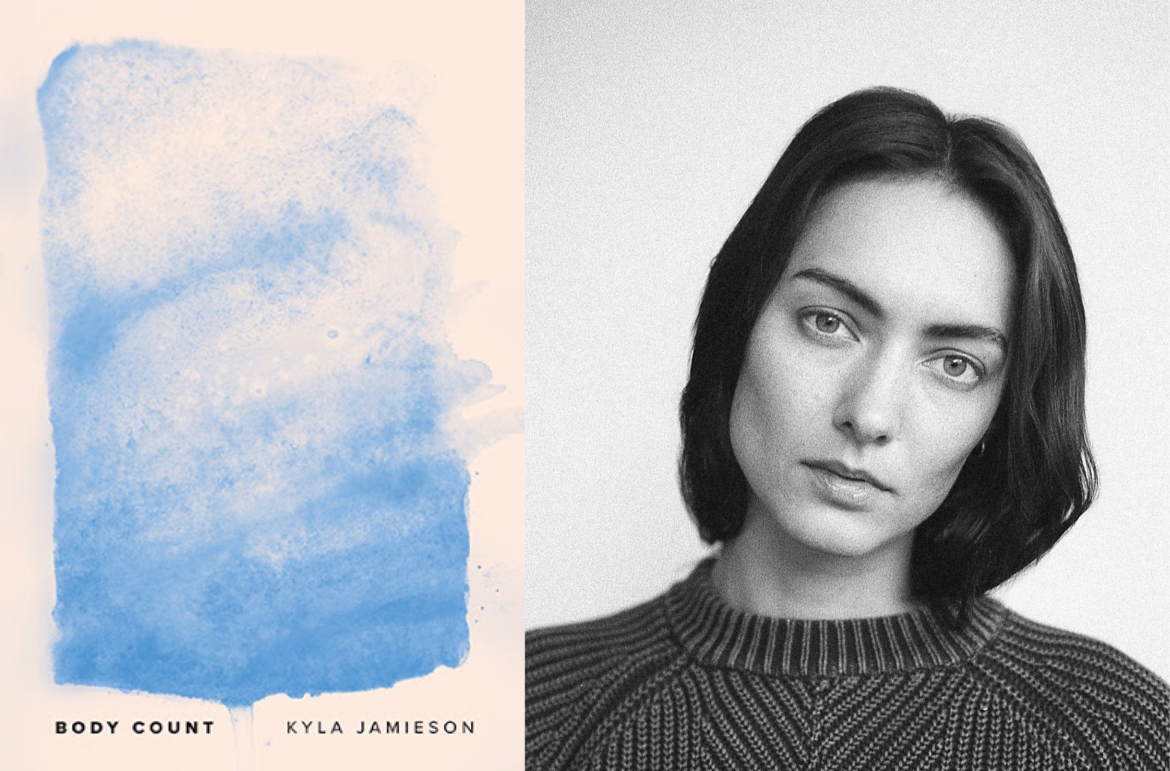

Reprinted with permission from Body Count by Kyla Jamieson (Nightwood Editions, 2020).

Rob Taylor: The second half of Body Count is centred around, and transformed by, a concussion you experienced. You write about “lying / in bed with a two- / week headache / bored & lonely / while everything / happens in sound / waves around me / & I can’t even / write a good / poem.” How did that inability to write, and do much of anything, affect the trajectory of your writing? What kind of a book do you think you would have written had the concussion not happened?

Kyla Jamieson: There’s no simple answer, because writing and living are so intricately entwined, and my concussion has impacted, and continues to impact, every aspect of my life — it leaves nothing untouched.

One thing that happens in the second half of my book is that the texture of time changes as I shift from living on normative time to living on sick time. Alongside that shift, my focus narrows, because when I wrote these poems my world was constricting around me. With the loss of my peripheral vision, my area of vision became smaller, and my headaches felt like my skull was contracting around my brain. I was housebound most of the time, and this was before pandemic-era Zoom brunches, so both my social circle and the physical space I occupied narrowed.

“What happens to your writing when reading’s not an option? What happens when physical and virtual worlds are inaccessible to you? What happens when what brought you pleasure — sunshine, reading, movement, conversation — brings you pain, or is unavailable to you?”

For a long time, the furthest I’d get from my apartment was four blocks, when I’d go for walks on this walking route I developed that avoids traffic noise and has crossing lights at the busy intersections. It’s scary to cross the street without peripheral vision, especially when drivers and cyclists think you look “fine” and that you’ll be able to see them or to move out of the way. Meanwhile, I didn’t have the reading capacity to roam around the internet, either. My capacity to travel both physically and mentally was altered.

So many people read as part of their writing processes. What happens to your writing when reading’s not an option? What happens when physical and virtual worlds are inaccessible to you? What happens when what brought you pleasure — sunshine, reading, movement, conversation — brings you pain, or is unavailable to you? The second half of Body Count is my answer to these questions. If it weren’t for my concussion, I would have been asking and answering different questions.

You mentioned our sudden new era of Zoom brunches. I think a lot of people who have gone through a major event in their personal life, as you have with your concussion and recovery, are finding it surreal to watch everyone collectively deal with the upheaval of the COVID-19 outbreak, having experienced their own upheaval, alone, previously. How are you doing? In what ways do you see overlaps between what you experienced recovering from your concussion and what we are witnessing and experiencing now?

Isolation is not new to me. Getting groceries only once a week or once every two weeks is not new to me. Being unable to leave the house or see people and being unable to access basic healthcare is not new to me. I already know how the light falls inside my apartment at all times of days and in all seasons. It’s been three years since my injury, and symptom management is still my primary occupation.

I can see how this might sound bleak, but isolation has been my reality, and I’ve found ways to live within the restrictions my disability imposed, rather than waiting for it to be over so I could go back to “normal.” Right now, I see people questioning normalcy and who the status quo serves more than ever. Crisis can force re-examinings, it can be generative, but the cost can be unbearably high.

If I may, a few pandemic pieces by disabled writers that I’d recommend: this Grazia essay by Mimi Butlin — filed under “Health & Fitness,” because the perspectives of chronically ill folks are now considered relevant instead of fringe; this Vice piece featuring Sharona Franklin, the artist behind one of my favourite disability-related instagram accounts, @hot.crip; and Liz Bowen’s newsletter from New York.

Yes, of course! Thank you so much for those links, and for bringing in new ways of looking at and thinking about the world. Your book does a lot of that, too. In “I’m Not Better I’m Just Less Dead” you write “I have nothing / to offer Literature / or Capitalism / not even a body / just an illness.” Similarly, you write in a subsequent poem “Has illness / made me more / or less human?” All of that struck me, the separating of the body, the self and the illness, each influencing the other but apart from it. It made me think about “me” in a different way. Which of those parts (the body, the self, the illness) do you consider “you” and which feel outside of “you”? From which do you think these poems emerged?

I think I was working at the Prose Editor at PRISM international when I wrote that first poem, but I could barely read, and I was hiding the extent of my symptoms because I didn’t want to lose my job. I couldn’t review books, I couldn’t host or attend events, I couldn’t hang out with other writers or read their work. The amount of labour I could do, either intellectually or physically, was really limited. And so much of the messaging we receive, implicitly and explicitly, is that our value is rooted in our productivity, our ability to labour in particular ways and under particular conditions. That’s part of the reasoning used to justify and perpetuate ableism.

When I became disabled, I simultaneously became less useful to capitalism (except insofar as I was spending everything I had on rehabilitation) and some of the people around me, and more useful to myself and the people who understood me. I think the self is the core, but it can’t be cleaved from the body, or the ways illness imposes itself on that body. These poems came from a need to make that imposition visible, and unmistakable.

You and Kayla Czaga have a little back-and-forth going in your two books. A section of Czaga’s Dunk Tank is written to you and the second poem of Body Count is a reply from you entitled “Dear Kayla.” Czaga opens her sequence with the lines “You told me the epistolary form broke / your silence, Kyla,” and your devotion to poems-as-letters is borne out in Body Count, which features poems written directly to Czaga, and also “Adèle” (Barclay, I assume), “Frank,” “Libby,” etc.

How did the epistolary form help “break your silence”? What does writing directly to a particular reader allow you to do in your poems that otherwise feels elusive or impossible? When you write non-epistolary poems, do you still have a particular reader in mind?

“Feeling like I didn’t have to defend myself, or convince anyone to be interested in what I was saying, being able to explore rather than explain, and knowing my reader cared about me—all of that was transformative for me.”

Before my poems-as-letters there were emails-as-letters: over the course of about a year my platonic life partner Libby and I each wrote 70,000 words to each other. About the present, the past, our thoughts, our bodies, our lives. Writing to someone who knew me and understood me was what allowed me to find a sense of freedom in my writing again after years of stultifying creative writing workshops. Feeling like I didn’t have to defend myself, or convince anyone to be interested in what I was saying, being able to explore rather than explain, and knowing my reader cared about me—all of that was transformative for me.

In her book Love Speech, Xiao Xuan/Sherry Huang writes, “the moment of address is the tear in the air we need to get going.” I think there’s an energy that comes from addressing someone. The poem has the energy of conversation. Of trust or sometimes transgression. It’s intimate, it feels private but you have permission to be there. Whenever I write a poem, I’m writing it for the person who’s going to get it. I’m not interested in writing towards anyone I have to impress, or protect myself from, or perform my pain for, because I’m not interested in being vulnerable within that kind of dynamic.

As mentioned, one of the people you address in Body Count is the poet Adèle Barclay. She not only appears in poems in Body Count, but she also edited your chapbook, Kind of Animal, which was published last year by Rahila’s Ghost Press. Can you talk about Adèle’s role in making this book happen, both in terms of her editorial work on the chapbook (many poems from which appear in Body Count) and otherwise?

Adèle is phenomenal — as a writer, an editor, a mentor, and a friend. I interviewed her years and years ago, and she shared something Brenda Shaughnessy had said to her: “She said not to worry about trying to fit in because in a few years poets are going to want to fit in with me.” It was so important to me to know that you could not fit in and still get a book published and have that book do well, because at the time I was in my MFA but I was not getting published, I was not being encouraged in the direction of my interests by my professors, I didn’t fit into CanLit, and I didn’t really want to, either. I looked around me, and it seemed like the people with book contracts weren’t necessarily better poets than the people without them—they were just the ones who kept going, who wrote enough to put a manuscript together.

I think that’s when it clicked for me that it didn’t really matter what my professors thought of my work. I could move in my own direction, and if I could be my own source of encouragement, and dedicate myself to my own vision, I could have a chance at a book deal, too. I sort of said to myself, “I’m going to put a manuscript together, and then people can reject it. But I’m not going to let the expectation of rejection, or other people not understanding or supporting what I’m doing, stop me before I even get to that point.” I made that decision after I’d let other people’s criticism inhibit my work in a really big way, because I knew I didn’t want to repeat that cycle. Adèle had also gone through trying times in academia, and seeing her move beyond those obstacles and prove that loyalty to your own vision can pay off gave me hope.

You talk openly about your trying times in academia in Body Count. In “F for Effort” you write about a mentor who wanted you to be “great / I guess like america?” and you later note “I don’t think / I’m trying / to learn what / they’re trying / to teach me.” The competition and careerism of grad school writing programs can often be disorienting, especially for poets who I think understand more intuitively (or at least ought to) that the rewards of the writing life are far removed from the book sales, awards or accolades. Can you talk more about the gulf between what you wanted out of your education in writing, and what was offered?

Those lines in “F for Effort” reflect on working with American mentors I had at the Banff Centre who were very successful, established novelists. I felt like they wanted me to aspire to greatness, when all I wanted was to not feel triggered all the time. They weren’t malicious at all. I think a lot of it was rooted in differences between American and Canadian literary culture, but it did echo this feeling I had at UBC that the spaces I hoped to find inspiration and guidance in weren’t going to come through for me in the ways I’d expected them to.

During my MFA, competition and careerism just felt like part of the landscape—they didn’t register as concerns for me. 2015 through 2017 were, to put it mildly, difficult years to be a Creative Writing student at UBC, especially as a woman, and a feminist, and someone whose trauma history is flooded with male violence. I think sometimes people who’ve had a lot of power for a long time forget the weight of that power, they forget their responsibilities to their students, and they forget what it’s like to lack power. I witnessed and experienced manifestations of this particular kind of amnesia throughout my time at UBC.

I pursued my MFA because I wanted a writing life — I wanted to have a voice in the world, and I wanted to hone that voice. But the messaging I received was that my voice was a liability, not an asset — that it would “get me in trouble.” I almost wasn’t hired to edit PRISM international because I was seen as “too outspoken.” But I also knew, throughout my degree, that the same institution that tried to muffle and confine my voice would also happily take credit for anything I accomplished in the wider world. I knew this because I’d talked to alumni, I’d heard stories, I’d seen how adjuncts were treated. The institution is shameless. It will claim any cultural capital it can.

One exception to what you describe here seems to have been UBC professor Keith Maillard, who you thank in your acknowledgments for his “words of encouragement and solace.” Could you talk about the role Keith played/plays in your development as a writer, and what he’s shown you about how mentorship relationships can be done well?

Keith was the second reader for my MFA thesis, so we only had one meeting, but his feedback was, “This is a publishable manuscript — send it out. It will touch many people.” I’m paraphrasing, because I can’t find the piece of paper, but I had it pinned to the bulletin board above my desk for months. Alongside understanding what I was trying to do with my writing, Keith demonstrated a real acknowledgment of the power he had within the institution, and did so in a way that was very moving to me.

Support isn’t genuine if it comes with an expectation of obedience. You can’t say, “I’ll support you if you do things my way.” That’s not support, that’s control. Good mentorship balances taking responsibility for the power you have with a lack of attachment to your place in the hierarchy. You have to respect the people you’re mentoring, and be willing to work in service of their vision for their work, rather than imposing your own.

You talked earlier about your work as Prose Editor at PRISM international. What did sifting through the slush pile, and making the difficult decisions of what gets published, teach you about the Canadian writing world?

“I learned how necessary it is for magazines to demonstrate to people writing from these perspectives that they’re invested in, and receptive to their stories.”

I hesitate to draw conclusions about the Canadian writing world at-large based on my time at PRISM or our slush pile, because when I started the magazine still had a reputation of being kind of establishment or status quo and not championing the work of marginalized writers, and I think that perception likely influenced who was submitting. I will say that there was not an abundance of work being submitted by trans folks, sick folks, disabled folks, Indigenous folks, poor or low-income folks, sex workers, incarcerated or previously incarcerated folks, or other groups that have historically not been celebrated by the Canadian writing world. I learned how necessary it is for magazines to demonstrate to people writing from these perspectives that they’re invested in, and receptive to their stories. It’s not enough to just include a note about diversity in the submission guidelines.

Turning back to your own work, your chapbook Kind of Animal came out just one year ago! It must have been a little odd to go from editing the poems for the chapbook straight into editing the poems for Body Count, especially when they were often the same poems. Were there other ways you rethought/revised your approach to the poems from Kind of Animal when you returned to them? Did publishing Kind of Animal and seeing it out in the world spur new writing for Body Count, as you saw possible new opportunities of where to fill gaps or go in new directions?

Most of the poems in Kind of Animal are also in Body Count. With my chapbook, I had a very particular reader in mind, and a very specific purpose, which was to make poetry about my concussion and post-concussion syndrome available to people who knew what I was talking about but maybe, because they weren’t writers, or because of their own concussion symptoms, struggled to articulate it. Aside from the first four poems, which are there to ease readers into the text and establish the voice and narrative identity, each of the poems in Kind of Animal speaks really specifically to some aspect of living with a concussion, from descriptions of symptoms to the frustration of not being able to afford care. Body Count encompasses all of that and more. The frame is wider, and ideas that were under the surface in my chapbook come up for air.

The dominant shape of a poem in Body Count is icicle-like, one long, skinny stanza with each line containing no more than 3-5 words. There are many exceptions to this, of course, but this seems to be your “go to.” Have you always written in this shape? Why do you think you are drawn to it?

The short answer is Eileen Myles. I’ve been a fan of their work since I found a copy of Chelsea Girls in the library and carried it around in my backpack all summer with my queer longings like it was the one person who got me. Their poems introduced me to that narrow shape. “Five Parts Rape Poem One Part Self-Care” is one of the first poems I wrote for my book, and one of the first poems I remember writing in that style, inspired by Myles and this incredible Morgan Parker poem, “If You Are Over Staying Woke.” I actually started writing that poem at Adèle’s apartment, during a little poetry séance.

“Five Parts Rape Poem One Part Self-Care” is about literary culture and rape culture and being gaslit both within the institution and outside of it, and I submitted it for a poetry workshop at UBC. There was a “fuck you” in using that shape, and taking up space, using up so many pages, to say things I felt people really didn’t want to hear or didn’t want me to say. We were always being told to “tighten” things up, to condense, to compress. This form and the colloquial tone are kind of the opposite of that. There’s more space in and around the poem. There’s room to breathe, even though the poem itself is kind of breathless. It didn’t work for me to use the poetic structures we were taught in class to undermine or critique the institution. I needed a form from my own canon to carry what I was saying.

Your attention to form as being essentially bound to content is also evident in your concussion poems. A notable shift happens in one of the book’s first concussion poems, “Sex Wave Moon Nest,” where the words are spaced out within individual lines, and line breaks appear everywhere, sometimes separating nothing more than a single piece of punctuation. It’s a striking change from the poems that precede it. Can you talk about the choices you made in that poem, specifically, and more generally how your concussion influenced how you thought about how you physically display your thoughts on the page?

“Sex Wave Moon Nest” takes that shape because it’s one of the only poems from the second half of the book that I wrote on my computer. Having a whole page that size to work with felt like it allowed me to cover more ground, and to physically represent the fractured nature of my memory, thinking, and reality. But working on my computer was difficult for me — my concussion made me need reading glasses, but I didn’t get to see a specialist who could pinpoint that issue until over a year after my injury, so I was struggling that whole time. I went back to writing poems on my phone, because the narrow boundaries of the screen held the words together in a way that allowed me to see what I was writing.

The thing with something like post-concussion syndrome is that the distance between what you’d like to do and what you can do tends to be painfully vast. I had to write about what I could access, which was often just my own symptoms or memories or body, using the forms and tools that I could work with, and not get hung up on what eluded me.

A tension between beauty and utility runs through Body Count. It manifests as a tension between direct statement and metaphoric abstraction, and also between rejecting the feminine and embracing the beauty within women’s bodies. “Self-Image So Far” works with these themes, as does the book’s epigraph, by Ariana Reines (“I don’t need the luxury of representation / Just tell it to me”). The book ends on the image of a tree, its branches filled with spring flowers, and the thought “Yes, I can hold all this beauty up.” Elsewhere lines like “I think she / wanted my sentences to do more / to be more purposeful / like a man” (“F for Effort”) and “before I wanted to be pretty I wanted to be on time” (“Body Count”) expand this set of considerations.

How did writing this book, and thinking through all the things its poems think through, influence your feelings on beauty, in both poetry and in the world in general?

My relationship with beauty is complex, because it was central to my livelihood as a model for years and was the reason that, as a teenager, I found myself in some pretty horrific situations. In my mind, there are so many ways to draw a straight line connecting trauma and beauty, but I feel like very few people see it that way.

“I’m almost thirty and I’m just now learning, in a way that both my mind and body believe, that it’s not inherently bad or dangerous to engage with beauty. “

For a long time, disassociating from beauty and rejecting it, by quitting modelling and refusing to wear makeup, or cut my hair, or buy new clothes, was one way I tried to both cope with trauma and keep new trauma at bay. Part of healing from my past trauma, which is a process I started anew when I began trauma therapy in the aftermath of my concussion, has been acknowledging beauty, allowing it to be present in both my life and my writing. I’m almost thirty and I’m just now learning, in a way that both my mind and body believe, that it’s not inherently bad or dangerous to engage with beauty.

Intellectually, I knew that engaging with my own beauty didn’t give people permission to violate me, but my body and subconscious mind had learned otherwise so young, and our culture tells us otherwise so often, that I struggled to internalize this truth.

There’s such a gulf between knowing a truth intellectually and truly feeling it inside. Maybe writing it out is part of that journey from one to the other. Another journey written out in Body Count is your journey away from silence and towards asserting yourself in the world. In the title poem, you write “I used to think I could trade obedience for safety,” and in the following poem you add “I am beginning / to think of myself / as a historian / of my own / silence / I am trying / not to repeat it.”

Your outspokenness is testified to in this interview, and also in Kayla Czaga’s sequence of poems for you. In “This is Garbage!,” she writes that you “always open / bags of other people’s garbage / and say, This is garbage! / while I hang air freshener and say, Maybe this is ok.” Could you talk a little about this journey from historian of silence to garbage calling-outer, and how it manifests in your poems? Connected to the question on beauty and utility, how do you balance the need to have poems speak out and yet still contain silences, moments of reflection, etc. (if you desire such a balance at all)?

I feel like every poem is an exercise in saying something true. I guess it becomes “speaking out” when that truth doesn’t align with the status quo, or articulates something that’s supposed to remain unsaid. Whether a poem seems political or not, what I’m trying to do is articulate my experience in a way that has the potential to make others feel seen.

I’m not saying, “Hey, rape culture is real.” Within the realm of my work, that’s a given. What I’m saying is, “Here’s how my body feels within this culture, and I don’t know how you feel, but does this make sense to you? Is it maybe adjacent to how you feel?” I think this goes back to the question of who I’m addressing. I’m always exercising the muscles I developed writing to Libby. I’m coming at it like I’m talking to my best friend.

One of the fundamental questions I ask myself is how I want my work to make people feel. Where do I want to take people, and what do I want to leave them with? Can I leave people feeling like they’re closer to themselves than they were when they started reading? I never want to remind people of injustices that might have a very real connection to their own lives without also offering some kind of comfort or hope.

Join Kyla Jamieson at the launch of Body Count on Instagram // Sunday, April 26, 1:00 p.m. EST @airymeantime

Kyla Jamieson is a disabled writer who lives and relies on the unceded traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Room Magazine, Poetry Is Dead, Arc Poetry Magazine, Vallum, Peach Mag, Plenitude, GUTS, and The Account. She is the author of Kind of Animal, a poetry chapbook about the aftermath of a brain injury. Her first book-length collection of poems, Body Count, placed third in the Metatron Prize for Rising Authors and was recently released by Nightwood Editions. Find Kyla on Instagram as @airymeantime or at www.kylajamieson.com.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.

Read more 2020 National Poetry Month features here.