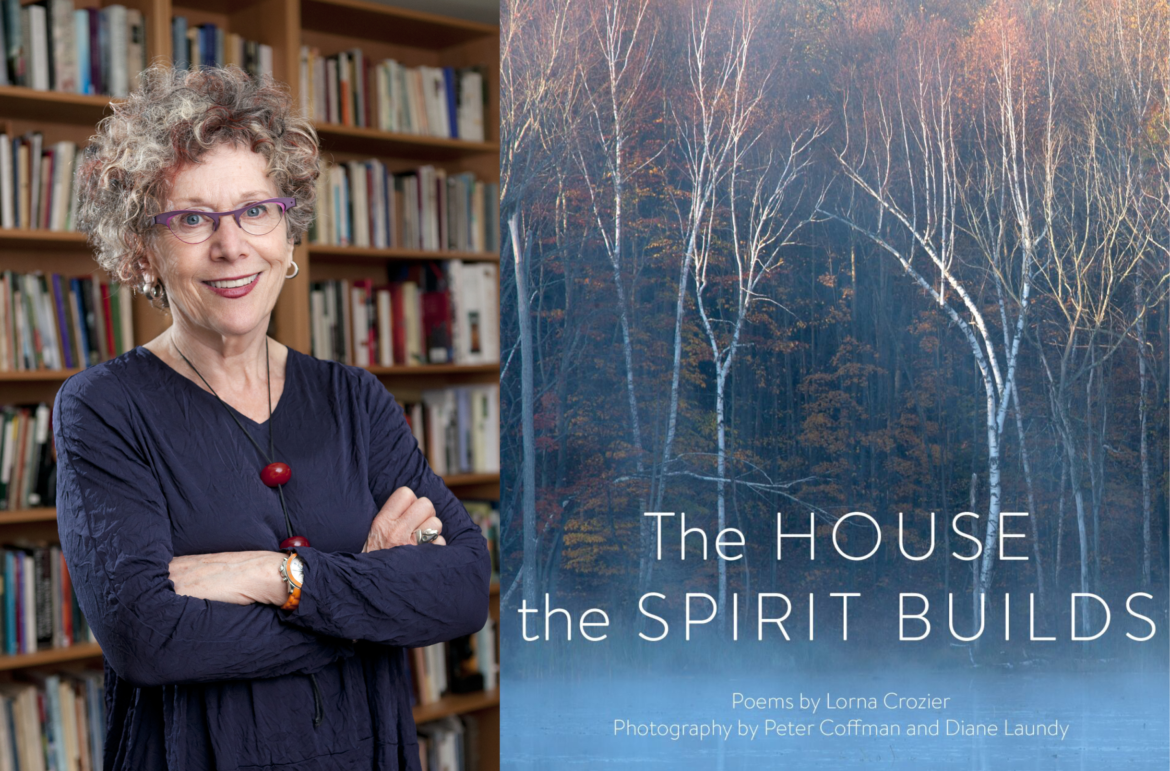

The following interview is part three of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. It is also part two of our interview with Lorna Crozier (you can read part one here). New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2020. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Blessing

Its is-ness,

the inner spark

that makes it grass—

not twig, or word, or feather—

leaps from inside

and ignites

the seed head.

Nothing you know

of rain, of grief,

of darkness

can put it out.

Reprinted with permission from The House the Spirit Builds by Lorna Crozier (Douglas & McIntyre, 2019).

As I prepare these questions, I’m sitting beside a stack of thirteen of your books. Nearly every one of them is dedicated to your husband, Patrick Lane, who died in March 2019. Unique among your dedications is the one that opens The Blue Hour of the Day, which was published soon after your mother’s 2006 death. You dedicate the book to her, and follow the dedication with a quote from Patrick’s poem “Fathers and Sons”:

Wait for me. I am coming across the grass

and through the stones. The eyes

of the animals and birds are upon me.

I am walking with my strength.

See, I am almost there.

If you listen you can hear me.

My mouth is open and I am singing.

This same quote open’s Patrick’s 2004 memoir There is a Season. I suppose I just wanted that quote to live here, as part of this larger conversation, and to say that I’m so sorry for your loss. And, since this is an interview: a question. You’ve written in any number of places over the years about how Patrick’s writing and partnership shaped your own. Are there ways in which, when you write, you can hear his voice in there alongside your own?

Thanks for bringing back those beautiful lines from Patrick’s poem. My mouth is open and I am singing. It makes me weep. I hear his voice everywhere: even when I turned on the radio at 5 a.m., on March 8th a year ago, the morning after he died, when I lay in the darkness of our bedroom, for the first time knowing I would wake up forever without him, after having been together for forty years, there he was on the CBC national news, reading a line from a poem, “Some days there’s just too much rain,” followed by an announcement of his death. It shocked me, hearing his rich baritone coming from a place where I couldn’t reach him. It washed over me with warmth and comfort, until it didn’t. Until I registered what it meant. I was hearing his voice on the radio because he was dead.

I imagine in some way, your garden and the forest across from it (where you together cleared the ivy), must be another way his voice reaches you. In There is a Season, Patrick quotes your poem “Garden Going on Without Me” and says “it pointed the way to [his] sobriety.” Your garden in Victoria clearly meant a great deal to both of you in your life and writing. Have you had much time to work in the garden of late? If so, how has that space changed for you since Patrick’s passing?

Patrick was the gardener and I was his assistant. I’d ask him what I should deadhead and how low I should cut the plant. I’d ask what was a weed and what was new growth. I’d ask how much fertilizer to apply to the Spanish moss around the pond and then say he should do it. And I’ve discovered, sadly, as in many other ways, I depended on him, I’m not doing well in the garden on my own. I don’t even know if I like gardening. It was one of the things we took joy in together and now that I’m on my own with a gigantic garden, it is overwhelming. Anyone out there who wants to grow vegetables? I’ve got the plots—I’m serious. I’d like them to be enjoyed by someone who delights, as Patrick did, in growing things. He used to tease me when he’d say at readings we did together, “I planted sexy vegetables so Lorna could write about them as if she knew them, but it was my garden.” He was right.

Oh, I’m sorry to hear that, though it’s entirely understandable. I’m hopeful that it means new things will come your way to fill that space (and maybe new gardeners, replying to your open call!).

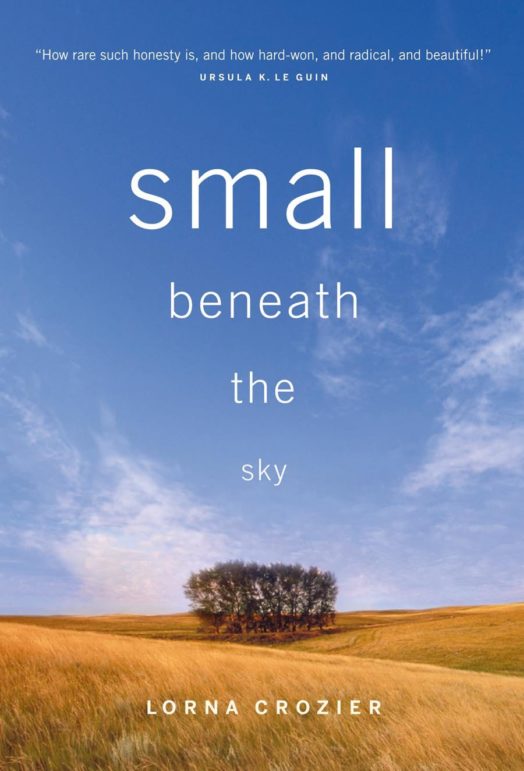

I’d like to ask you a little about your memoir, Small Against the Sky, which was published in 2009, five years after Patrick’s There is a Season. I often think of poetry and non-fiction as the genres with the most overlap (especially for more confessional poets), so I am always curious why an autobiographical poet takes a turn at writing memoir. What, or how, did you want to explore in Small Against the Sky that wasn’t available to you in poetry?

“I do find that poetry and a certain kind of non-fiction wear the same jacket, whereas poetry and fiction don’t.”

I do find that poetry and a certain kind of non-fiction wear the same jacket, whereas poetry and fiction don’t. I wrote the memoir after writing several essays, usually at the request of anthologists like Carol Shields for Dropped Threads. What I submitted to Greystone was a collection of the essays, which they accepted and I signed a contract, but when I met with my editor, she said she and the publisher actually wanted a different book, the story of my growing up in Saskatchewan. I didn’t want to write it. For one thing, I said to her, the word memoir has two “me”s in it, English and French, and I didn’t think my life was interesting enough to turn into prose. I came around by convincing myself that I’d write not about me, but about how landscape shapes character and how a class system exists even in small-town Canada, though few would admit it. I do find that creative non-fiction allows more room than poetry, not only in the obvious way—it is longer—but it allows for more description, more diversion, more concentration on character and dialogue and plot. Yet I still fell back on including prose poems, as punctuation marks or breathing spaces, throughout the manuscript between the chapters. I thought if I fail with the non-fiction, I’ll still have the poems.

Poetry is always a solid backup plan! What role did being with Patrick as he wrote and published his memoir have on your writing one of your own?

Patrick had an almost photographic memory about his past. When he wrote There Is a Season, the scenes unrolled in his mind like a film. I don’t remember things that way—I told him I didn’t remember enough to write a memoir. His advice? Start writing and it will come back to you. He was right.

You mentioned ghazals earlier – how your teaching the form at University led you to testing it out yourself. In Bones in Their Wings, your collection of ghazals, you write about your experience reading the ghazals of John Thompson: “Sometimes, if readers are lucky, in a certain writer’s life form and content come together like two strangers who know they are about to experience a great and passionate love.” Thompson’s ghazals obviously had a direct influence on Bones in Their Wings, but what lessons about form and content did they teach you that you carried with you into your writing in general? What’s caught up in your great and passionate love?

“A musician friend told me her jazz trio leader said to them, “Take it to the left.” That’s kind of what I learned from the ghazal and what I’d like to sneak into my poems.”

I’ve written a few series of ghazals since I read John Thompson’s wonderful book. Before Bones in Their Wings, they appeared as a section in two books and in one after (The Wrong Cat). But even if I don’t explore that form again, it shows up in my work. I am fascinated by how to incorporate the leaps between the couplets, characteristic in the ghazal, into a poem that is not a ghazal. A musician friend told me her jazz trio leader said to them, “Take it to the left.” That’s kind of what I learned from the ghazal and what I’d like to sneak into my poems. How do I execute the unexpected, the surprising, in the middle of poem. Yet the turn shouldn’t feel cheap or contrived. The swing to the left should startle but be the right way to go. That’s what I got from the ghazal—the disunity being part of the unity, the surprise being a surprise that deserves to be there.

Poets quote favourite writers in epigraphs often enough, but in both Small Mechanics and Small Against the Sky you write about John Berger being fundamental in inspiring some portion of the writing, which feels like a “next level” of engagement. Could you talk about how Berger has caused you to think about your poem (and world) differently?

Oh, John Berger! One of his questions is forever embedded in my mind: “What does it mean when an animal looks at you?” And he had such a respect for the local rural people he lived among in France. He learned from them. For instance, and I’m quoting this from memory, so it won’t be exactly right, he said the farmer down the road wouldn’t say, “We loved the pig but we killed it to eat the meat,” he’d say, “We loved the pig and we killed it.” For me, learning from Berger, I hang upon that difference between “but” and “and.”

Your books of late have largely been published by two presses, Greystone and McClelland & Stewart, though other presses have appeared here and there (Douglas & McIntyre, Hagios, Freehand, etc.). As you are writing a book, do you already have a sense of what “home” you’d like it to end up in? What’s coming next?

I’ve had a kind of unspoken agreement with M&S, my main publisher since 1985 (god, that’s a long time ago) that I will bug them only every three years. No one bangs on a poet’s door, at least not my door, because most of us are not making anyone money, including ourselves. Greystone was a good home for my memoir and the publisher, Rob Sanders, bullied me into writing it. Freehand asked me for a book, hoping for prose poems, I think, but what I had was poetry and they graciously accepted it. They hadn’t done poetry before. The book I’m working on now is about living with someone you love who you fear might be dying. I started it three years ago when Patrick fell ill because besides caring for him and loving him and worrying, I didn’t know what to do to survive. I went, as I have always done, to words.

For the first time in my life, I found an agent, and he sent it to M&S, who accepted it. It’s coming out this fall. Interwoven in the months of our despair are scenes of our lives together—how we met, how we fought and laughed and partied and loved and wrote poetry. It’s called Through the Garden: A Love Story (with Cats). It’s also a biography of the five cats we lived with in our forty years and the book ends, not with Patrick’s death, but the death last November of the cat we named Bashō.

* * *

Click here to read part one of this interview.

Lorna Crozier is the author of several books including Small Beneath the Sky (Greystone, 2009), The Book of Marvels (Greystone, 2012), and What the Soul Doesn’t Want (Freehand, 2017), which was nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry. She is a professor emerita at the University of Victoria and an officer of the Order of Canada. She lives in North Saanich, BC.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.

Read more 2020 National Poetry Month features here.