The following interview is part eight of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2019. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Excerpt from Bounce House – Jennica Harper

Once, within twenty-four hours, I’d washed

both their hair. Each fine & lightly waved,

the saturation darkening, straightening. One

had been a wash of mercy: fingers massaging

a scalp untouched for weeks. Then the other,

to get the guck out, honey & brambles, detritus

of a day not worth remembering – that one had

been a mercy for the washer; for these hands.

Reprinted with permission from Bounce House by Jennica Harper (Anvil Press, 2019).

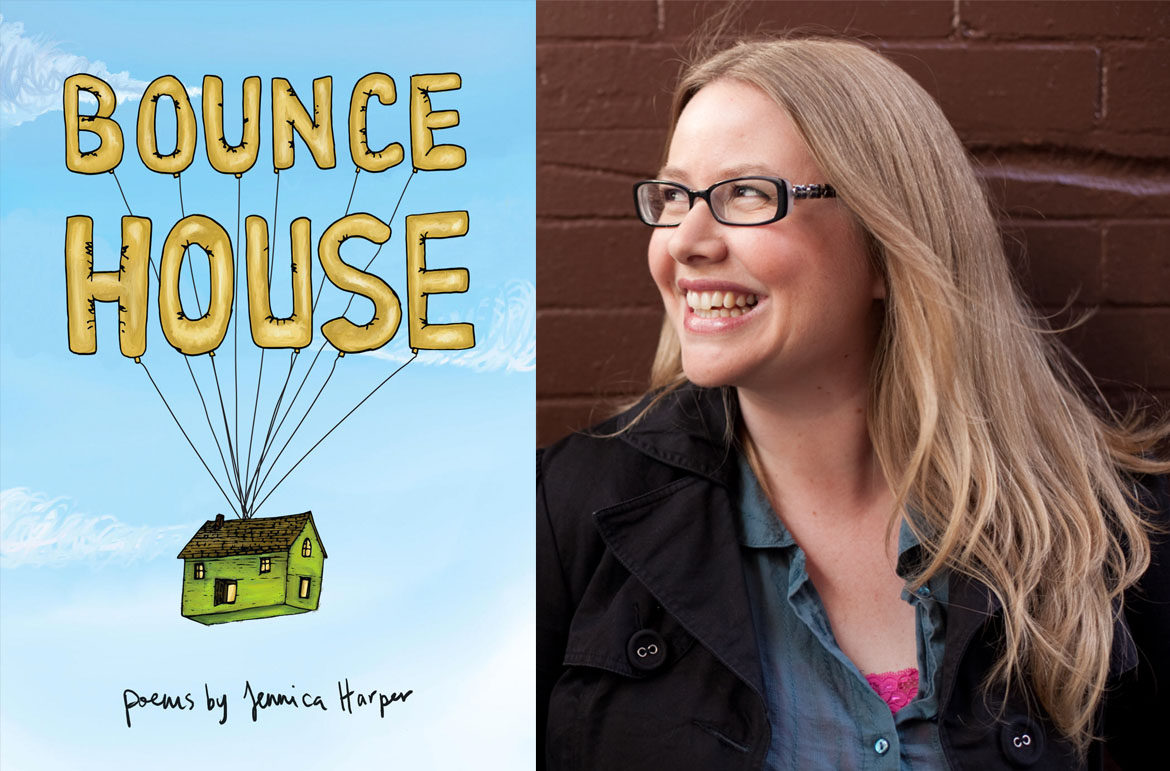

Rob Taylor: Bounce House, your forthcoming Anvil Press book, is a long poem which explores that in-between place many young parents face: raising a new generation (their children) while losing another (their parents). Just as you start to gain insights on your own parents (having become one yourself), they begin slipping away from you.

In your poem the speaker is stretched between the world of her young daughter and her dying mother (which involves cross-country flights, underscoring the great divide she’s trying to hold together). Mid-way through the poem you write: “I’d worn her pearls to the funeral. / Dressed in floral, like a woman or // a woman in costume as a woman.” Could you talk a bit about what raising your daughter taught you about your mother, who died in 2017? What watching your daughter being raised taught you about yourself?

I always understood, intellectually, that everyone was a child once, including my mother. But when I was bouncing back and forth between helping build a world for a kid and watching the world be un-built for my mom, I really felt it in my gut. That my mom was once a kid, a teenager, a young woman entering hopefully into a doomed marriage. That my kid would one day be where I am, waiting for me to die – sometimes impatiently. And that my kid would one day be the one dying.

I suddenly had much more empathy for my mom. There’s a poem in the book that alludes to the fact that when I was young, I changed my first name. I felt, for the first time, how that might have hurt my mother (even though the name Jennica was her idea.) I feel almost hyper-aware of the little wounds each generation inflicts on the others. A full life means lots of little wounds.

Oof. Yeah, ain’t that the truth. I love how deeply you explore this difficult set of realizations: a poem on the theme that’s so long it spans a whole book! That said, Bounce House isn’t your first book-length poem/suite of poems. That was What It Feels Like For a Girl (Anvil Press, 2008), and after it came Wood (Anvil Press, 2013) which contained multiple section-long suites of poems on particular themes, often written in particular styles.

I’m interested in how you come upon a writing “project”: do you write one-off poems and then find a theme or style gathering between them, or does the idea come first and the poems follow? I’m curious particularly about how Bounce House came to be: did you take the same type of approach as you did for previous books?

I don’t start a book thinking “this is going to be a book.” I can’t think top-down at the beginning; that comes later. So far my approach has been to just start writing. A couple of poet friends (Marita Dachsel and Laisha Rosnau) and I periodically set aside a month and commit to writing a poem a day. Sometimes this results in some great writing (much of both Marita’s and Laisha’s recent collections were drafted as poem-a-day poems).

For me, I have found the daily writing practice doesn’t usually result in great poems, but it does make me realize what’s picking away at my brain. I often discover the thing I want to write about this way – looking at 10 drafts of poems and realizing what they have in common. Bounce House began with a poem-a-day poem contemplating the connection between my kid standing on a basketball, not believing she was going to fall off it, and Flat Earthers. For a couple of weeks, I wrote these short poems about my daughter, my mom who had recently died, and kind of meditated on the globe, basketballs, and all things round. Once I started seeing themes within those quick drafts, I started new poems with more intent.

Wow, that’s amazing that your poem-a-day months can be so productive! I can’t imagine pulling that off. Do you still write single poems, and if so, will you ever find a way to give them a home, or is it themed-books from here on out?

I do sometimes write single poems! But I fully admit I’m drawn to groupings. I don’t know why. If I write a one-off I like, I sometimes search for a jumping-off point within that poem to another one.

The form of the poems in Bounce House—four couplets per page—is very compelling. It features the compression of a haiku (or, dare I say, a tweet), the appearance of a ghazal, and the energy of a sonnet (short, square-ish, with that last couplet often snapping it into place at the end). How did you come to this shape? Why do you think it worked for this particular book?

The four-couplet shape was instinctive more than conscious… I think of them a little like pithy sonnets.

Thank you! The four-couplet shape was instinctive more than conscious. It’s not dissimilar to the form of the poems in What It Feels Like For a Girl: they’re also four-couplets apiece. I do think of them a little like pithy sonnets.

If the form works for this particular book, I think it’s because the piece overall isn’t narrative so much as meditative or impressionistic. I hope the poems add up to a whole, but it’s not intended to be linear and come to a “conclusion” per se. In fact, there was a time in which my editor Michael V. Smith and I discussed the possibility that the book might be presented as cards that can be shuffled and read/experienced in any order. That didn’t feel quite right in the end, but I do feel that these little boxes exploring one, or maybe two ideas, provide pieces of an experience without necessarily all the connective tissue. I leave that to the reader.

As you’ve now written in this particular length and shape in two books, to what extent has writing this way become natural to you? Did you start “thinking” in the form, and not needing to corral them much to get them into the shape, or was it always a struggle to edit into being?

Have you written much poetry since you finished Bounce House? If so, did you find it easy to “shake” the form and write something else?

Michael’s argument to me was that there was great tension in just the compact poems, and I should lean in to that. Let the tension remain without defusing it; let people be uncomfortable even.

While the four-couplet shape was natural, the drafts had wildly varying line lengths. They were much less boxy. There were also a number of poems interspersed throughout the manuscript that weren’t four-couplet box poems. I thought of them as interstitials.

But both my first trusted reader, Marita, and my editor Michael pushed me to keep the form consistent: the poems as boxes without the “filler” of the other poems in between. I think Michael’s argument to me was that there was great tension in just the compact poems, and I should lean in to that. Let the tension remain without defusing it; let people be uncomfortable even.

The truth is I needed the encouragement – I think I was instinctively leaning back from the intensity of the box poems. I needed to know they were strong enough and would carry the book.

It has been surprisingly hard to shake the form. I don’t think I’ve written a poem I’ve liked since finishing the book. Which I hadn’t fully realized until now. THANKS, ROB.

Ha! Any time. Now to get you to over-think another formal quirk in the book (it’s kinda my thing!).

Bounce House follows the growing trend of referring to presumably-real people by their initials. In this case, the daughter is “D.”, the brother “B.”, and the husband “J.” (which align with their real names, listed in the dedications at the end of the book). It seems to position the book in between autobiography and fiction—the character’s almost the real thing. But maybe I’m misreading that entirely! Maybe it just helps shorten the poems so they fit the boxy shape!

Why did you make the choice to use initials? What freedoms or restrictions do you think it put on writing about your “real” life? And, more generally, would you say this book is autobiography-in-verse, or—like the initials—a little adjacent to the real thing?

I didn’t know this was a trend! I thought it was an old-fashioned Victorian epistolary thing, very “Dear Reader.” There were two reasons I chose to use this convention. First, as you suggest – if it’s not their name, I’m not married to some kind of literal truth about these people. There’s some flexibility in the telling. The second reason was purely practical: I couldn’t imagine, in the size of poems I was writing, repeating those names over and over again. There just wasn’t space.

Picking up on this idea of “flexibility in the telling,” midway through Bounce House you write, “This is not a story. I want to narrativize / but the planks don’t meet clean. It’s all // slivers and gaps between the slats.” Beyond how damn lovely this is—the sound of it!—these lines contain an interesting statement on poetics, for the book and perhaps for writing in general, with the couplets as planks and the white space between them “all slivers and gaps.”

Poems don’t align, not entirely. They have gaps (and slivers!) inevitably, and often intentionally. If a poem’s “truth” isn’t a narrative truth (if the “truth” that a poem tells is not a “true story”), then what is it? What kind of truth (if any) are you seeking as a reader when you pick up a book of poetry, especially a book which contains seemingly autobiographical first-person narrative poems? Are you looking for something different than what you’re looking for when you pick up a (prose) memoir?

I’m not as interested in narrative truth as I am in authentic emotion (including ugly ones). My goal is to get closer to that truth: finding something raw and real.

Thank you again. I’ve thought a lot about what I want a poem to be. At one point there were more “meta” poems in this manuscript but, like the “interstitial” poems I’d had at one point, they defused the tension too much. I had a lot of drafts of poems that were asking: “Why write these poems at all?” That’s an internal conflict I have much of the time (“Who cares about this?”) and more than ever before with this book. People have parents who die, and people have children who need raising, and what is so special about my voice on either subject? Can I write something that is both wholly true and actually, you know, interesting?

The conclusion I’m coming to is I’m not as interested in narrative truth as I am in authentic emotion (including ugly ones). My goal is to get closer to that truth: finding something raw and real. I don’t think I’m perfect at this. It’s just a goal. I hope Bounce House gets at a particular way of experiencing grief – non-linear, circling back on itself. Maybe some readers will relate to that emotion, if not my specific experiences.

Speaking of themes that have traditionally been unfairly hampered by “Who cares about this?” questions, Bounce House is also “on trend” in that it’s part of a larger surge of writing on motherhood (this Spring season alone sees books specifically on motherhood by Elizabeth Ross and Adrienne Gruber, as one small example). Do you have any thoughts on why that’s happening now? Did any particular writers, or books on motherhood, inspire you in taking on this project?

Has it been so long, in the grand scheme of things, that women have been writing about motherhood? No. Not compared to men writing about lovers. So bring it on!

Feeling like I was part of a trend was definitely daunting for me. As I mentioned, I really wasn’t sure I had anything unique to bring to the subject. On the other hand, has it been so long, in the grand scheme of things, that women have been writing about motherhood? No. Not compared to men writing about lovers. So bring it on!

I was almost explicitly not reading other writers on the subject when I was working on the book. Some poets that were influential (not formally, but in energy) were Ada Limon, Sina Queyras, and Kim Addonizio.

On the theme of influences, Bounce House opens with a Van Halen quote—”Might as well jump. Jump!”—which is one hell of a way to start a poetry collection! Reading the book, though, the song lyric that kept returning to me was “She means we’re bouncing into Graceland” from Paul Simon’s “Graceland”(late in the book you refer to death as “slip-slid[ing] / into the dark,” which seems like another nod to Simon). The girl from New York City who calls herself the “human trampoline” feels so at home in this book of bouncing balls, spinning globes, and turning wheels; of falling, flying, and tumbling in turmoil.

When in the process of writing the book did you come to the title “Bounce House”? Was it in any way tied to Simon’s “human trampoline,” or do you think yourself and Simon were just on similar wavelengths when it comes to the good and the bad, the joy and the danger, of bouncing?

This is amazing. Slip-sliding is definitely a reference. But now I’m wondering how much of Paul Simon is in the book – in spirit if not directly. The complete Simon & Garfunkel collection was in constant rotation in my house growing up. At my mom’s service, we had a singalong to “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” And after she died, I saw Paul Simon live for the first time, and could not stop connecting songs to memories of her. So it’s entirely possible he’s everywhere in this.

The title came from a phrase used in a draft of a poem that never made it into the collection. But isn’t it fun to say? So round and pleasing.

And it led to a hell of a cover! It and the book’s interior are illustrated by poet andrea bennett. The interior images consist of whimsical line drawings of the (largely) circular objects mentioned in the poems (a quarter, a basketball, a ball of yarn, etc.). The objects aren’t always located next to the section which mentions them: sometimes they precede the mention and sometimes they serve to remind us of a previous section of the poem. How did the idea of interior illustrations come about? How do you think the book reads differently with them in there?

They are largely round objects! I was tempted to keep them all round, but andrea had ideas for other ones (for example, the House of Birthday Cards) that I liked too much not to include. Choosing the images was very collaborative – I had some I knew I wanted, and she proposed some. But for the most part, they’re circular. Spheres amongst all those boxes.

The idea for illustrations was instinctive. I just had a feeling that this might feel a little like an artifact instead of a conventional book. I think they serve partly as breaths between movements. I wanted the order to be fluid because that’s really what I wanted to get at: memories returning unexpectedly. Everything part of the churn. And I wanted the reader to sometimes be anticipating some motif or moment that had yet to come. I resisted logic and linearity – I wanted the experience to be full of undertows. To be messy.

You work as a writer and producer for television, most recently as co-creator and executive producer of the CTV comedy Jann. That, combined with parenthood, must not leave must space for your own creative writing. How/where do you fit the poetry in?

I’m very excited and grateful that another form of writing is my “day job.” I love what I do. Poetry definitely takes second (really maybe seventh?) priority. But I like the balance. When I have time to return to poetry, usually during longer hiatuses from TV, it’s an amazing change of gears. What I love about my poetry life is there’s no pressure there. None of the intense deadlines I get in my TV life. I find it freeing and really rewarding to come back to. Like a summer romance…

Do you find writing for TV influences your poetry in some way, or vice-versa?

Nothing thrills me more than figuring out how to say something in the fewest words possible and still have an impact.

I think there are a lot of similarities between screenwriting and poetry. They’re both about crafting an image, and often use language economically. Nothing thrills me more than figuring out how to say something in the fewest words possible and still have an impact. Which you’d never guess from the answers to these questions!

As an interviewer who asks long-winded questions, I’m not about to throw stones at your bounce house over your thorough answers. I love it!

At the end of the book you thank two poets, Michael V. Smith and Marita Dachsel. You’ve talked a bit about each of them here, but could you expand on the role both of them have played in your life, and in the creation of this particular book?

Marita is my best friend and first reader for all my poetry. She’s been instrumental in how my last three books came together. She actively helped me with the order and structure of What It Feels Like for a Girl. And she’s the one who, after I wrote a poem about Sally Draper having an abortion, insisted I write more Sally Draper poems! Which I did, for Wood. For Bounce House, Marita helped me figure out what the heart of the book should be (and what I should leave out). Basically, I trust her to prevent me from making a fool of myself!

Michael V. is a wonderful friend and an extraordinary writer. I hadn’t asked him to read or edit my poetry before, but I had read his book My Body Is Yours (Arsenal Pulp Press) on one of the weekends I was visiting my mom in the hospital. One aspect of the book is Michael’s father’s death, and all the big and small revelations surrounding it and their relationship. I was moved by the book and how Michael wrote it with such clear-eyed self-awareness and empathy for his father. And I love Michael’s poetry. It seemed a natural fit to ask him to edit the book, and I’m so grateful he said yes. He was incredibly supportive yet honest, and pushed me a little, which is what I wanted.

Speaking of long-term collaborators, this is your third book (and eleventh year!) with Anvil Press. What has that relationship been like for you? In your acknowledgments you specifically thank Brian Kaufman and Karen Green at Anvil for their “faith”: do you think their continued support of your writing has influenced the kind of projects you’ve taken on, or perhaps bolstered your courage to go after them?

I’m really grateful Anvil has allowed me to go in VERY different directions for all three of these books. They don’t expect me to have a “brand” – they’re supportive of me and seem to be fine with me pursuing really different kinds of work. I do think feeling like I have a “home” with Anvil allows me to pursue experiments and take risks.

Jennica Harper is the author of three previous books of poetry: Wood (Anvil Press, 2013), which was shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize, What It Feels Like for a Girl (Anvil Press, 2008), and The Octopus and Other Poems (Signature Editions, 2006). Her poetry has been translated for the stage (Initiation Trilogy), gone viral, and won Silver at the National Magazine Awards. Jennica also writes for television and lives with her family in Vancouver.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best Canadian Poetry in English (Biblioasis, 2019). In 2015, Rob received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for the Literary Arts, as an emerging artist. He lives in Port Moody, BC with his wife and son.

Read more 2019 National Poetry Month features here.