The following interview is part seven of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2019. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Market and Metal – Cassandra Blanchard

On Hastings there’s a black market of sorts that goes on for a block

where one can find things like steaks and porn and clothes, people

have their shopping carts full of junk and dealers hustle the crowd,

Glen and Kim and I used to drive a large old van around scrounging

for food in the back lot of the Superstore and then selling it

on the street, this block is crowded and when police walk the beat

the crowd disperses fast like mice and then regroups, we also used

our van to collect metal and sell it at the junkyard and if you collect

enough you can get quite a bit of money, those old radiators are

good to scrap, once a big truck went by and a chicken fell out

and sat there in the middle of the road and for a minute I thought I was

seeing things cuz it came out of nowhere and it was one of those

poultry who can’t walk anymore and two seconds later a dude took

the chicken, probably to sell it in Chinatown I don’t know, but I felt

sorry for that chicken and I would have carried it to the SPCA but the

man was quicker than me so that’s how it goes.

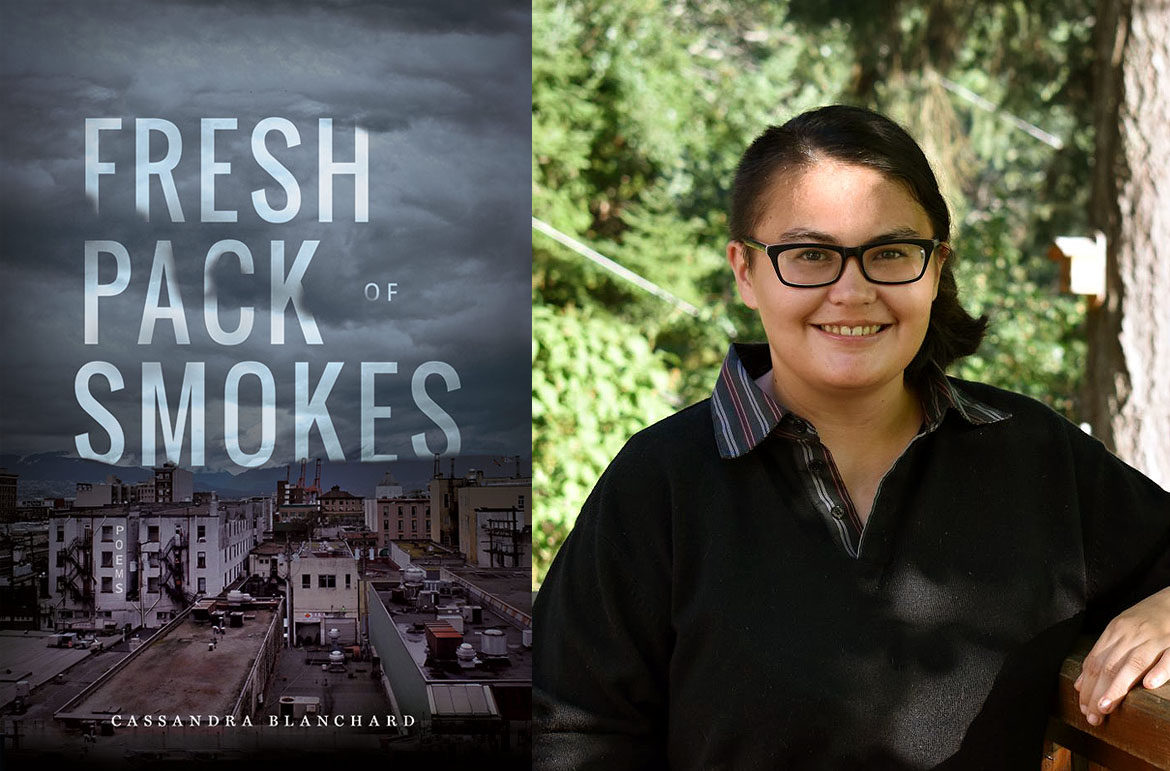

Reprinted with permission from Fresh Pack of Smokes by Cassandra Blanchard (Nightwood Editions, 2019).

Rob Taylor: Your debut poetry collection, Fresh Pack of Smokes (Nightwood Editions), is described by your publisher as a book exploring your years “living a transient life that included time spent in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside as a bonafide drug addict” in which you “write plainly about violence, drug use, and sex work.” From that description, and from the raw honesty of the poems themselves, it feels like a memoir-in-verse. Do you think of it in that way: as a memoir as opposed to something more creatively detached from you? Is the distinction important to you?

Cassandra Blanchard: I have written poetry since I was a young teenager and it is a medium that I am very comfortable with. It is also the best way in which I express my feelings and experiences. As for Fresh Pack of Smokes, I would say that it is a creative memoir. I write of my life experiences like a memoir but in a creative form. I would also say that this book has been a cathartic process for me, something that releases all the pent-up emotion. So it is a mix between creativity and memoir, though it is all nonfiction.

Yes, you can absolutely feel the pent-up energy being released in so many of these poems. You mention that you’ve written poetry since a young age. Is that why you turned to poetry instead of a more traditional prose memoir?

I didn’t start with the intention of doing a traditional memoir … I wanted to make a record of what happened to me and poetry was the easiest way to do that.

I didn’t start with the intention of doing a traditional memoir. I didn’t even really think that much about how these poems would fit within the definition of a memoir itself. I wanted to make a record of what happened to me and poetry was the easiest way to do that. I also thought it would be more interesting for the reader to read poems than straight-up prose.

I was drawn to poetry as a means of communicating my story because it was the best way for me to express myself. As I went along, I found that it was also the best way to lay out descriptions of events, people, and locations. The poems are basically one long sentence and I find this captures the reader better than the traditional form.

One long sentence—yes, that’s often true! Many of the poems in Fresh Pack of Smokes feel like they were written in a stream-of-consciousness style, moving freely from one image or memory to another. How do you approach the writing of a poem? Do you usually write the first drafts in one sitting, producing that one long sentence quickly, or do you piece them together in a more methodical way over a longer span of time?

For Fresh Pack of Smokes I wrote down the poems in exactly the way I thought of them, from sentence to sentence. I didn’t do drafts for the poems, I just wrote them in one sitting and then fiddled around with commas and periods. My editor, Amber McMillan, did edits that consisted of grammar changes and small things that made the poems more polished and flow together better. When I write poetry I don’t do different versions, I mostly just lay it all out pretty quick. The main thing is that I write it how I think it.

All of the poems in Fresh Pack of Smokes are prose poems. What draws you to this form? Did you write them all this way from the beginning, or did you transform these poems into prose poems at some point further down the line? Do you read, or think about, a prose poem in a different way than you do a more “traditional” poem with line breaks?

I have always been drawn to prose poems, or prose, that channels a stream-of-consciousness. I love how it feels like you’re peeking into the mind of the poet or writer. Earlier drafts of Fresh Pack of Smokes included a few poems I’d written in the “traditional” form but they never really meshed with the rest of the book so they were cut. I don’t really know why I wrote them. I probably wanted to mix it up a bit. However, the meat of the book takes on the prose form.

Prose poetry feels more genuine to me because traditional poetry seems to take so much work to write and structure it.

While these poems are all prose poems, the length of those poems varies significantly: from a few lines to a page and a half. Some of the poems seem to reach a natural conclusion, while others end abruptly: jarring the reader in a way that compliments the jarring subject matter of the poem. Many of the poems could flow easily from one into the other, as one larger piece. Did any of the poems go through major revisions (perhaps trimmed way down, or split into two poems, or combined, etc.) during the editing of the book? How do you know/sense when to end a poem?

It’s kind of hard to explain how I know when to end a poem. Sometimes I know it should be finished after a few lines and sometimes I know it should be longer. When I can’t think of anymore lines to write I stop. The poems finish themselves basically.

All of these poems have distinct titles with the exception of “Love,” which recurs in seven different iterations (“Love I,” “Love II,” etc.) in the book’s second section. It’s obviously an important theme for you! Why did you centre it in the book in this way? How do you think ideas and manifestations of “love” have changed for you between the time of addiction and sex work, and now? In what ways have they stayed the same? Did the writing of the “Love” poems influence your thinking on the concept in any way?

My editor was the one who thought of naming the poems “Love I,” etc. She managed to put together the poems that all had the same theme of love and desire. The “Love” poems are about intense feelings that I had for people, that I had for drugs, and that others had for me. The feelings I had for drugs were so intense that it was like the feelings of love between two people.

Between now and my active addiction, I think that the meaning of love has definitely changed. I say this because back then I was in love with crack cocaine; it was the most important thing in life for me. Now I see love as family-based and for special friends. Drugs no longer have a place in my life but I for sure was in love with it. I wouldn’t say the “love” poems have influenced me at this stage in my life but it is interesting to see how I saw love back then.

In “Love V” you talk about how you “would just listen and these women would pour their hearts out.” It made me wonder: who listened to you when you most needed to pour your heart out? Was writing these poems a way to create a listener for yourself? More generally, do you think writing or reading poetry can be therapeutic in a way akin to sitting and talking (and really listening) to someone?

I absolutely believe that poetry can be a kind of therapy for people. It was for me.

I have had a counsellor for a long time, especially during those years I was actively involved with drugs and the lifestyle that goes with it. During those times, I was very lonely and felt quite isolated and my counsellor was the only person I talked about things with. So she was the person I poured my heart out to even though I would sometimes go a long time between appointments. Eventually, she reported me missing to the police youth squad, but I contacted her again after a while. I also talked to people while in rehab and so forth.

Did I create a listener with these poems? I don’t know the answer to that question. I absolutely believe that poetry can be a kind of therapy for people. It was for me. Releasing all those feelings through writing helped to relieve a lot pent up emotion. Reading my poems makes me feel so glad that I have changed my life around.

In your acknowledgments you thank poet, author, and editor Amber Dawn for supporting you “since the beginning,” and poems of yours have appeared in Dawn’s chapbook anthology Sex Worker Wisdom and forthcoming full-length anthology Hustling Verse, edited by Dawn and Justin Ducharme, to be published by Arsenal Pulp Press in Fall 2019). Could you speak about the role Amber Dawn has played in your life, and your development as a writer?

Amber Dawn has been absolutely instrumental in my journey as a poet. I studied her book Where the Words End and My Body Begins (Arsenal Pulp Press) in university and I was awed by her poetry. It inspired me and I decided that I should try to write about my experiences too. I contacted her on Facebook and told her I wrote some poems and she said she would read them. I sent 10 poems to her and she said they were good. I felt encouraged, so I continued to write more poems and about a year later, I sent them to Nightwood Editions. Amber has been a mentor to me, too. She explained the publishing process, read my contract and gave me feedback about it. When I have questions about anything related to poetry or publishing or readings, I ask her. I am very lucky to have such a friend.

Yes, you certainly picked the right person to connect with.

In poems like “Jail” and “Drying Out,” you discuss the connection between jail and waiting/down time, and how it allowed you to “recover my mind and body” and “face the person I was.” You also note in the poem “VGH,” of being hospitalized, that you were “grateful for the pause.” What role did your time in prison play in leading you to writing? Do you think of poetry as something which offers you these same things: a pause, some recovery, a chance to face the person you were?

Poetry isn’t really a pause, but it is a way to face the person I used to be.

Jail saved my life. I was in such a horrible downward spiral that I think I would have died sooner than later. A tap on the shoulder would have done nothing—I needed to be knocked off my feet. Jail forced me to stop everything and, even though you can get drugs in jail, I detoxed and stayed clean. Jail didn’t make me grow as a person, but the four months I was in it did give me the pause I needed. Even though I continued to use after jail and after rehab, that pause really did save me.

Poetry isn’t really a pause, but it is a way to face the person I used to be. I read some of Fresh Pack of Smokes and I see bits of myself that now I am embarrassed by and also afraid of. I don’t think I was the greatest person, but I do see a kind of innocence that wasn’t crushed.

There’s certainly an element of this book that is about you writing about/to/for yourself. At the same time, many of the poems in Fresh Pack of Smokes explain in some detail aspects of the inner world of drug use, drug dealing, and sex work. One such poem is “Dial-A-Dope,” which describes how it was safer to have the dealer drive to buyers: “maybe on the street you could score pretty fast there is always a risk of getting ripped off because that window of opportunity between the moment you have cash and the moment you get your drop is what goofs live for.”

Poems like this one seem to be guiding readers through a world they may be unfamiliar with; a conscious effort is being made to bring “outsider” readers along with you. Was that always a goal of yours, right from the first drafts, or did the editing process involve adding a lot of explanations? More generally, how do you think this book will be read differently by people who have lived, or are living, in these worlds, compared to those who have not?

I wanted the book to be therapy for me and an education for others. It had always been a goal of mine for this book to be a guide to the areas in life that some have no knowledge of. The explanations were always there, there was no adding.

If I didn’t write these poems and instead was a reader who knew the drug world, then I would think that the writer of these poems knows what I have lived or am going through. The knowledge is there. To readers who have not gone through these things, I assume they would read the poems as a series of explanations. This book is an educational tool.

You’ve mentioned here and there some elements of working with Nightwood Editions. Could you talk more about how the book ended up with them? You hadn’t published poems widely before the book came out, so how did it come to Nightwood’s attention?

In May 2017, I submitted four poems to the Nightwood Editions submissions page on their website. I was just surfing the internet looking for somewhere where I could submit poetry. In November. I got a response from Nightwood asking for my full manuscript. It was a surprise because I had almost forgotten that I had submitted something, as seven months had gone by before they contacted me. So I sent my manuscript and then they wanted more poems because my book was pretty short. Time went by and a few months later they offered to publish in Spring 2019. Amber McMillian at Nightwood is an awesome editor and I was lucky to have her edit my book.

Vancouver has been “mapped” poetically by any number of poets, including George Stanley (Vancouver: A Poem), Meredith Quartermain (Vancouver Walking) and Michael Turner (Kingsway). I would put Fresh Pack of Smokes in their company: so many intersections, parks, and buildings in the city are present and palpable in your poems. Do you think there is something particular about Vancouver that causes such interest in writing about the city with great specificity? Why did you choose to describe the city in such detail, down to individual streets and neighborhoods, when you could have told your story in a more generalized way?

I feel like Vancouver is a living entity infused with the good, the bad, and the ugly.

I have mixed feelings about Vancouver. I lived in the city for many years before I moved to Vancouver Island. I loved my neighborhood in Mount Pleasant and I like Vancouver as a whole. However, there is a really dark underbelly to the city, and it can suck you right in if you let it. It is this underbelly that I wanted to talk about. I also wanted to express how the city affected my experiences of addiction. To do this I decided to focus on specific areas of Vancouver where I spent time. I feel like Vancouver is a living entity infused with the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Speaking of writing about the city, I’m curious about what portion of this book was written while you were in Vancouver, and what portion was written elsewhere? Did where you were writing change how you thought/wrote about the city and your years living in it?

Of the book’s 67 poems, 39 were written in Vancouver. I wrote the rest in Duncan and added them to make the book a little longer. I don’t think it made a difference in which location I was writing in.

That’s interesting. I would have thought having more distance (physical, and in time) from your experiences in the Downtown Eastside would have altered the poems a bit.

Speaking of gaining distance from your drug addiction: the book ends with a suite of poems about getting clean. In “Clean” you write, “I’ve had so much excitement, if you can call it that, in my life that I won’t mind if the rest of my years are simple and quiet.” Will writing be a part of that simpler, quiet life going forward? And if so, do you have anything in mind for what you might write next?

I love writing so much I can’t imagine my life without it. It will for sure be a part of my life now and in the future. Right now I am currently dabbling in short stories. I love creating different worlds and characters. So I think that is my next step.

Cassandra Blanchard was born in Whitehorse, YK, but called Vancouver home for many years. She holds a BA from UBC with a major in gender, race, sexuality, and social justice. Her poetry has been published in a handful of literary journals. Fresh Pack of Smokes is her first book of poetry. She lives in Duncan, BC.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best Canadian Poetry in English (Biblioasis, 2019). In 2015, Rob received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for the Literary Arts, as an emerging artist. He lives in Port Moody, BC with his wife and son.

Read more 2019 National Poetry Month features here.

One reply on “Therapy for me and an education for others: An interview with Cassandra Blanchard”

I am so proud of you my neice. I will be looking for this book to purchase and share with my family. Queries have been answered from this interview. Mussi-cho