The following interview is part four of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2019. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

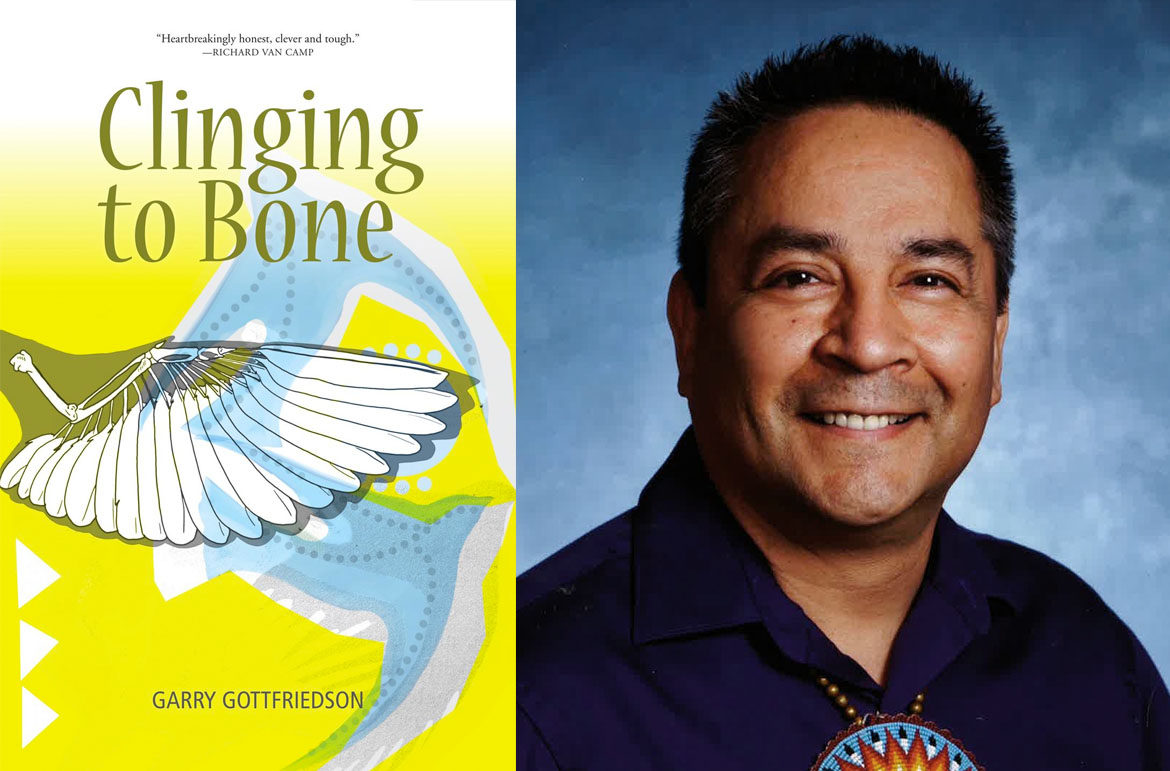

Clear Memory – Garry Gottfriedson

the years whip

grey into the hair

so subtly

we have lived many storms

dreamed many nights away

time softened our hearts

brushed clear memory

out on the yellow canvas of sky

another day meant renewed life

another night meant bones rested

some things are meant

to be forgotten

but I remember all of you

Reprinted with permission from Clinging to Bone by Garry Gottfriedson (Ronsdale Press, 2019).

Rob Taylor: You include many Secwépemc (Shuswap) words in your new poetry collection, Clinging to Bone (Ronsdale Press). These include words for the Secwépemc people, language, and territory, but also more eclectic choices: sesi (sweetheart), sllwéltsin (autumn), teníye (moose), etc. These words are often defined in the poem itself, and then a second time in a glossary of terms at the end of the book. What motivates you to use these words, and to provide ample translations?

Garry Gottfriedson: Recently, I have started to incorporate more of Secwepemctsin into my writing. I decided to use some of these words because the image of them is poetic in itself. Sometimes, English doesn’t capture what I want to say, so I refer to my language. It is also a way to show my audience that we (First Nations) are still practitioners of our language and culture, even though we struggle to maintain it. It gives my audience glimpse into who I am, and my representation of my Secwepemc heritage.

I also think that languages are playful. Using words from both Secwepemctsin and English offers added dimensions to the body of the poem, the use of metaphor or even the poem’s rhythms. Using my language challenges my audience, too. Perhaps, my audience may be inspired to learn more about the issues and themes I present in my poetry.

I like that idea of playing and challenging at once. I think that’s very true to the effect it had on me. You were a teacher at Chief Atahm School, a Secwépemc-language immersion school, so you’ve obviously spent a great deal of time thinking about how to preserve and expand the use of the Secwépemc language. In “Bent-back Tongue,” for instance, you write, “truth or reconciliation is meaningless / words without bilingual reciprocity.” Would you say your goals in integrating Secwépemc words into your poems are the same as your goals were at Chief Atahm school, or does your intended audience for each shift your focus in some way?

Canada cannot truly expect a decent relationship with First Nations in Canada if the language that is used is only the colonizer’s.

I worked at the Chief Atahm School in Chase, BC as a teacher, and later became principal at the Sk’elep School of Excellence in Kamloops. In many of my poems, I make points regarding the “Truth and Reconciliation” attempts in Canada. One of the major issues I see with that process is that it uses the colonizer’s language to attempt to reconcile major historical and present issues in this country. Similar to the approach French Canadians have taken, Canada cannot truly expect a decent relationship with First Nations in Canada if the language that is used is only the colonizer’s. In a nutshell, only one frame of mind would be considered—the colonizers! Therefore by approaching truth and reconciliation from a bilingual perspective, we are on a level playing field. Two worldviews emerging into one view, so to speak.

I suppose this begs the question: why not use even more of the Secwépemc language in your poems? While you use twenty-two Secwépemc words in the book, you obviously could have gone further. What inspires you to use a particular Secwépemc word at a specific moment, and not in others? Does it change from poem to poem?

Yes, using Secwepemc words from poem to poem is often for a specific reason. Sometimes, it just sounds good to me or the image of what’s in my mind is clearer. Sometimes, using the English word is enough to express my poetic voice. I actually like using the English language because of the choice of words within the language. With my language, word choice usually is used for specific meaning and clarity, whereas in English, one word can have several meanings, and that is where the playfulness occurs in poetry.

That’s really fascinating. One element of learning and embracing other languages is what it teaches the learner about their first language. We all become richer in the process.

One country that seems to have embraced this idea is New Zealand, where you recently travelled. They are far ahead of Canada in integrating Indigenous languages into the daily life of the general population. Can you talk about your experience travelling there, and what it taught you about the way forward for Canada?

My trip to New Zealand has inspired me greatly. The Maori don’t take no for an answer when it comes to who they are, nor do they like to dance around politeness in politics or everyday life. They are extremely clear and straightforward about their desires to ensure that Maori and Pacifica cultures are stamped into the psyche of the politicians and average New Zealander. Their history is parallel to Canadian history in terms of colonization. They do not cower, being Maori, and have forced New Zealand to acknowledge the racism, injustices, colonial history, and genocide straight on. The Maori have redirected history in New Zealand for the sake of their survival as a unique and thriving people.

Canadians and First Nations can learn a lot from them. It is time now for Canadians to quit using a sophisticated and polite form of racism when it comes to First Nations in Canada, and it is time for First Nations to truly look forward to a positive future for our children’s sake. This can only happen by the true enactment of reconciliation. This is what New Zealand has taught me.

You spoke of how the Maori “forced New Zealand to acknowledge the racism, injustice, colonial history and genocide straight on.” I feel like much of your poetry is doing that same thing.

In “Confusion” you write “my poetry is / an arrow pointing at hearts / for those who are alive / remembering / the dead have yet to be heard,” and later in “Vienna” you write “no one will remember / me in history / I fought in no war / did not betray my people.” The question of who/what is remembered and who/what is forgotten looms large in your poems: to what extent do you see your own writing as an attempt at a corrective to the way Western cultures (or perhaps people in general) remember?

Let me begin by saying that anything is easy to forget. Sometimes it is because people don’t like to look at the dirty parts of history. And this could be because of many reasons. The ugly truth, however, is that if historical mistakes have been made, and they are not seen for what they are, it is then too easy to deny things really happened, and lies can easily be created. Or it becomes a one-sided version. I want my audience to understand what has happened to my people by Western cultures, so that action can be taken. I don’t want my poetry to necessarily put guilt on my audience. I do, however, want them to step into my world for a moment and see things from my perspective, educating them to some deep-rooted issues that are still not dealt with today. Let me put it in another perspective and ask this question: Can you imagine a world that didn’t remember Aristotle, or the Roman Empire, or the Renaissance, or the 900 years of Irish oppression by the British, or the impact of Hitler? Remembering is an essential part of history.

Absolutely! And I’m glad you made that comparison with European history which, while important, is disproportionately prioritized in our educational system. Your book does the reverse: prioritizing the Secwépemc people while still leaving space for others at the end.

The first two-thirds of Clinging to Bone focus largely on personal and political poems about the Secwépemc people and Secwépemc-settler relations (including the development of Sun Peaks, the health of the Thompson River, and the legacy of Residential Schools), but then the poems in the book’s latter sections travel around the world (New Orleans, Barcelona, Vienna…), widening the lens in a number of ways. Could you talk about why this was important to you in putting the book together? What light do you think these different poems/perspectives shed on one another?

I wanted to know if people were numb to their history and identity. It also was a way to understand my own essence of being a Secwepemc man. It is sometimes easier to clarify self-meaning when you are totally removed from your norm.

I wanted to include some of these travelling poems simply because I was a foreigner in many of those regions. It was a way to satisfy my curiosity about other people and histories. I wanted to see if other people from other countries remembered, or wanted to forget, historical events. For example, in New Orleans, what is their sense of identity and how was it shaped by the development of the city? In Barcelona, how did they remember Columbus and do they acknowledge how the gold he took built that city and empire? In Vienna, I wanted to find traces of how the World Wars began and to see if the people actually remembered it. It was looking at the consciousness of people. I wanted to know if people were numb to their history and identity. It also was a way to understand my own essence of being a Secwepemc man. It is sometimes easier to clarify self-meaning when you are totally removed from your norm.

In “Múlc” (Poplar Tree), you write of the impacts of settler colonialism (including ecological destruction and Residential Schools) on the Secwépemc people: “why did we not see it? // in the beginning.” How do you see the current state of Indigenous-settler relations? Do you fear Indigenous writers in the future will look back on our current moment and say, “Why did we not see it?”

I see the current state of Indigenous-settler relations as being in the early stages of change. At the same time, I see this process as awkward, uncomfortable, ugly, and beautiful. Sometimes, I see this relationship in silly terms, like a love-hate relationship, but it is necessary if Canada is to radically define who we are. In the end, if we can come to terms of a clear and meaningful relationship, then what awaits is hope for a great future.

It seems like we’re in the middle of a time of real growth for Indigenous writing in Canada, across all genres but perhaps especially in poetry. How does it feel to see it (finally) happening? Where would you like to see Indigenous poetry go next? Are there key Indigenous poets, either from this current wave of new writers, or older writers who went under-recognized, who you’d particularly like people to read?

Many of them have won major awards for their writing this past year, but it is more than winning that excites me. It is that they are courageous, and unapologetic about their work.

I have tremendous faith that Indigenous writers will not let our people down, while at the same time elevating the voices of Indigenous people much further than I could ever do. I believe the next generation of Indigenous writers will be the ones who will knock Canadians on their butts, yet they will also be the ones who will bridge a strong relationship with the settler population.

Take for example the works of Eden Robinson, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Jordan Abel, Joshua Whitehead, and Katherena Vermette. They are the future hope for change. I get so overjoyed thinking about their work, I actually get choked up. Many of them have won major awards for their writing this past year, but it is more than winning that excites me. It is that they are courageous, and unapologetic about their work. They may not have experienced some direct traumas that us older writers have experienced (like Residential Schools, etc.) but they experience the effects of it. Also, they aren’t afraid to write from a raw and new perspective reflecting what is real in Canada today.

In terms of older writers who are under-recognized, I think about Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm, Joanne Arnott, Chris Bose, and I so boldly include myself in that group.

As you should! You’ve toured widely, giving readings in North America, Europe, Asia and, as mentioned, New Zealand. When you were young, you also traveled across Canada performing Secwépemc songs and dances as a member of the Paul Creek Tribal dancers. Your poems have an obvious aural quality to them, and often seem built for performance. Do you write your poems, first and foremost, for performance or for the page? Do you think they have different “lives” when read on the page than when performed publicly?

My poetry is primarily written for the page, so the audience can digest them and re-read them. Having said that, some poems have to be read out loud (to hear my intention and voice) for them to move the audience into my experience. I am actually a very private man, so being in public is not a strength of mine, even though I’ve learned to work in that environment.

I absolutely think that poems have different lives when read out loud as opposed to on the page. I believe that poetry and the poetic voice is underrated. It is the true insight into the culture of the day. I come from an oratory culture, so active, live voice is critical. I think live poetry should be a major focus on the Canadian arts scene. I don’t think Canada does enough to promote this aspect of culture.

One aspect of how your poems live differently on the page than when spoken aloud is the physical shape of your poems. The poems in Clinging to Bone vary in stanza length, but they quite often stick with a certain stanza length throughout a single poem (i.e., a poem of all couplets or all quatrains, etc.).

At what point in writing a poem do you start to think about the shape on the page? How does a poem written in couplets read/”feel” differently to you than one with, say, five- or six-line stanzas?

The last part of my writing process is looking at the aesthetics of the poem, in the editing stage. I try to balance the appearance of the poem in terms of its stanzas and such. The first stanza in the poem dictates how the rest of the poem will appear. It is not intentional, it’s just how I write. It also all depends on how finished I feel the poem is. Sometimes they are long poems, others are haiku. But in reality, I don’t plan my poems out. I just let them drop onto the page, and then work them.

Skin Like Mine

(Ronsdale, 2010)

Clinging to Bone is your fifth book published with Ronsdale Press, all in the last 13 years (and three books in the last seven). Can you talk about your relationship with Ronsdale, which has involved both a long time span and frequent publication? Has that consistency given you more confidence or freedom in your writing?

Ronsdale Press has treated me really well. They have strongly supported my writing over the years. More importantly to me, Ronsdale Press has given me the freedom to write what I want. They have taught me not to compromise my poetic voice and have offered sound advice to maintain my poetic voice. This is something that illustrates belief in my work and the expectation that I will represent them with integrity. Truly, they have stood by me all of these years and have been loyal to my work. I can’t thank them enough.

Garry Gottfriedson is from Kamloops, BC. He was born into a rodeo/ranching family. He is an avid horseman, and is strongly rooted in his Secwepemc (Shuswap) cultural teachings. He holds a Masters of Arts Education Degree from Simon Fraser University. In 1987, the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado awarded a Creative Writing Scholarship to Gottfriedson. There, he studied under Allen Ginsberg, Marianne Faithful, and others. Gottfriedson has nine published books. He has read from his work across Canada, United States, Europe, and Asia. His work has been anthologized and published nationally and internationally. Currently, he works at Thompson Rivers University.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best Canadian Poetry in English (Biblioasis, 2019). In 2015, Rob received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for the Literary Arts, as an emerging artist. He lives in Port Moody, BC with his wife and son.

Read more 2019 National Poetry Month features here.