The following interview is part three of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2019. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Driving – Russell Thornton

I keep my headlights on, as recommended, even in daylight,

today and every day. In the night, when high beams strike my eyes,

I experience blind hate. Now I am walking across a street—

someone runs me down; I lie there fetal in the ticking glare.

They award me money, but I can never again run more than a few strides—

a dead leg, no spring in it. When I once ran races

and set records that stood for years. The steel screw and hinge

that had to be inserted in my knee now act as a transmitter and receiver

which communicate with me like a low-level deity; it sends an ache

the length of my leg alerting me to falling barometric pressure;

it signals me with my own yearning in the hour before rain—

now eternity will touch my entire skin at once. Now I ride

on a stationary bike at a rec centre gym for exactly thirty minutes,

my legs going around and around; I note the digits

indicating my achieved speed and distance. Today and every day.

I worry incessantly about the future, and my worry haunts me

like the past. Now I drive over a nail. At a repair shop, a workman informs me

he is not permitted to fix bald tires. Without my knowing it,

all four tires have lost almost all their treads. At any moment then,

on any icy or rain-slicked asphalt I might spin directionless, all my chances

gathered right there. And so I purchase quality new tires

that will take good hold of the road. I am vehicle-proud,

I am imitating a life, I am trying to do things right. Today and every day.

I take the wheel, click on the lights, and shine them invisibly into the light.

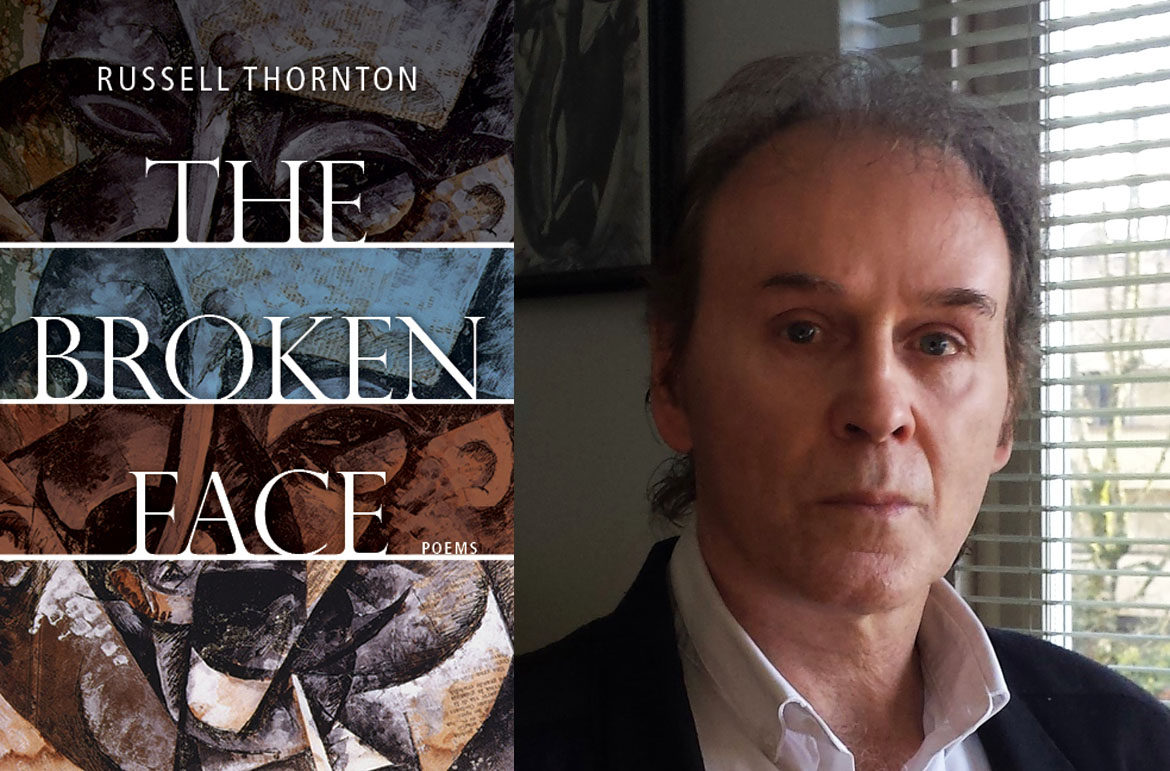

Reprinted with permission from The Broken Face by Russell Thornton (Harbour Publishing, 2018).

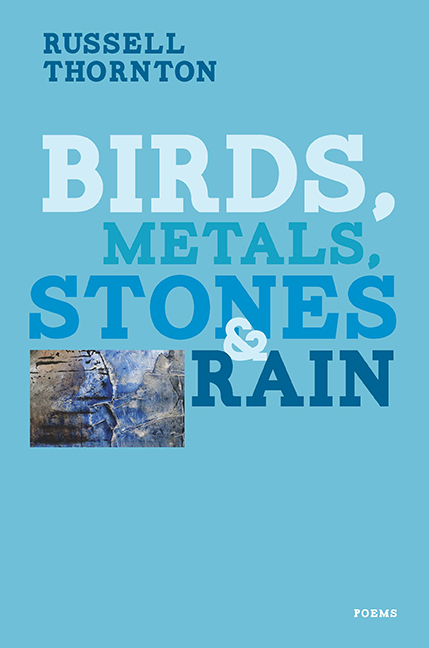

Rob Taylor: In many ways, your new poetry collection The Broken Face feels like a continuation (thematically, stylistically) of the work you were doing in Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain (Harbour, 2013). One commonality is the focus on the elemental: seemingly simple concepts/images are considered and considered again, until the great complexity hidden in them is teased out. I felt, though, like the particular “elements” you were working with here had changed.

The four major elemental themes in Birds, Metal, Stones & Rain were summarized handily in the title, and in reading The Broken Face I cooked up the alternate title “Prisons, Dreams, Mist & Light.” Could you speak a little about the “elements” that comprise this book (whether the ones I suggested or others) and your interest in focusing deeply on a handful of touchstone images/ideas in a book?

Russell Thornton: I meant Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain and The Broken Face to be part I and part II of a single enterprise. The images and ideas I’d tried to explore in the earlier book led me in the direction of related material, and I followed. With The Broken Face, yes, I wanted to try to burn away everything extraneous in my attention and expression, everything that wasn’t essential—to try to be evocative of what I’d refer to as the elemental strata of a human being. So I didn’t surprise myself when I found myself gathering poems around simple—and for me quite big—ideas and images.

One of the concepts that I kept returning to was crime; I knew that this was result of certain poems I’d produced for Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain. I’d say that mist and rain are favoured images with me. Light is as well—and the combination of light and rain (or simply water). Yeats said, “What’s water but the generated soul?” He was an unabashed neo-platonist; he must have believed like the ancients that water is “the first matter.” I’m not a neo-anything—but I am attracted to images and ideas that seem fundamental to me; they fit whatever psychic necessity I play out in my poems. This is also to say that the groups of elements in the two books are quite personal for me. And, yes, in both of these books I was circling images—conducting my own sort of circumambulatio. The process prompted the poems in the first book that are the most important to me; those poems prompted the pieces in The Broken Face that I devoted the most energy to and ended up feeling were the most successful.

Can we talk a bit about the one “element” I suggested which you haven’t touched on yet: dreams? Some of the poems in The Broken Face involve dreams explicitly, while others depict moments in the speaker’s daily life where present time “slips” or merges with the past, so that fathers, mothers, grandparents, children blur into one being (as in “Dandelions” and “Tying Shoes”). What do you think is drawing you to these types of poems at this point in your life (and writing)?

I’ve seen dreams as potent poetic content ever since I began writing poems. The texture of deep dreams—the symbolic plasticity and canny ambiguity—makes me trust their imaginative authority. I’m extremely interested in the relationships between waking consciousness and the unconscious, and between time and timelessness; I wonder about the operations at these interfaces. But then I suppose time and consciousness (along with love!) are principal themes of poetry.

A person is a strange conglomeration of realities.

In connection with the poems you mention, I guess the “one being” that people merge into is simply myself—or the self in attendance when I’m lucky enough to access modest but hopefully genuine levels of imagination. As I think many people do, I often feel the presence of people who are no longer alive—family members, of course, but also people I’ve never had any familiarity with in my waking life. In “Dandelions,” my dead grandmother merges with my small daughter and “teaches her to tell time”—as if a spirit stepped out of the other world into time for an instant or two. In teaching her to tell time, she teaches me about imagination and about the transactions between time and timelessness, and between daytime consciousness and the unconscious. In the other poem you mention, “Tying Shoes,” yes, I’m trying to capture an experience of bending to tie my own shoes and in that moment feeling I’m tying someone else’s shoes in the other world. A person is a strange conglomeration of realities, it seems.

The first section of The Broken Face is arranged in a fascinating way: you alternate between poems about your young son and poems about prisons. Could you talk a little about why you structured the section in this way, and how you wanted those poems to “speak” to one another?

I had my ideas regarding interlacing poems about my small boy with poems about prisons; it’s reflected in the ordering you mention. Silas White, who edited this book, helped me in the ordering of the poems. He’s quite adept at seeing the “narrative” of a book. I liked the idea of beginning the book with this section.

One of the major ways I thought of The Broken Face as being a “part II” of Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain was in the building on poems about memory, perception, place, the linking of generations, and fathers and sons, while adding a recurring overriding figure: the condemned man. With that first section, I wanted to introduce this figure—condemned for no reason other than his existence. That’s why the infant boy in the book’s first poem is lying on a set of scales and I say the arguments for both his prosecution and his defence are the same—his pulse. His pulse—and his infant human consciousness—can be viewed as a “fall” into life and as a crime. The boy is innocent, of course, and I’m projecting on to him what I see as the human situation; he is immediately in line to be apprehended by time and experience and be sullied and judged. The bits of naughtiness, incarceration, etc. that are to do with the condemned man in certain poems are autobiographical; they’re recollections of who I was as a younger person.

Alongside the autobiography, I intend the figure as an extended metaphor. He’s actually the speaker in the book’s opening poem, pronouncing the fate of the infant boy—the new version of himself. The boy is an exemplar of the first boy—Cain, let’s say—and thus of the first murderer. The condemned man figure is the father and a version of Adam, the first male parent. Right at the beginning of The Broken Face, I wanted to present something of the bewildering paradox of innocence and experience—and the relation of these states to acts of imagination. I wanted this initial section to elaborate itself through the book and inform all the other sections.

Innocence and experience, yes, that comes through in a palpable way.

When it comes to your own life experience, in addition to your youthful incarcerations (which inform portions of the book), you’ve also traveled and lived in many different parts of the world. Your bios at the back of Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain and The Broken Face mention that you’ve lived in Montreal, Wales, and Greece.

While you’ve explored these times in your earlier collections (most notably, The Hundred Lives), Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain and The Broken Face feel much more focused on your hometown of North Vancouver. To what extent do you think your deep exploration of North Vancouver (which lives as a vibrant, if wet, character in your poems) was shaped by your travels abroad? Do you think coming to know Greece (its mythology, history, people, poets) influenced your seeing/making the same in North Vancouver?

There’s a saying: “Travels are the soul of the world.” I think in travelling you sometimes enter a state of timelessness—pure process, pure potential, pure relationship. You’re on the way to a promised land—a place created perpetually in the imagination. Your question makes me think of the very great Greek poem “Ithaka” by C.P. Cavafy. I love the ending where the Cavafy/Odysseus speaker talks about how the idea of Ithaka gave him his “odyssey,” his 20-year journey, and how if he finds her “poor,” Ithaka won’t have “fooled” him, as it gave him the journey.

I haven’t been disappointed by own particular Ithaka, and I’ve been fascinated to see how an Ithaka can be both the home you left and not the home you left. When I was a teenager, I was desperate, as many teenagers are, to leave my familiar surroundings; I ended up going away for decades, coming back for brief periods to drive a taxi. Of course, I was desperate to access parts of myself that eluded me and were necessary for my psychological survival. And of course, at a certain point in travelling, you’re not dealing anymore with anything individual or personal that you need to open up in yourself; rather, you’re experiencing the more remote and unfathomable recesses and energies of the psyche common to all people.

I went into a cafe; everyone there seemed embarrassed to be alive.

I remember when I came back to North Vancouver after having been in Greece for three or four years; for an instant, as I walked along a section of Lonsdale Avenue the lower-rise buildings with storefronts made me think of military barracks. I went into a cafe; everyone there seemed embarrassed to be alive. And at that re-initiation into my place of origin, I felt like heading right back to the airport. But then, that night, I smelled the sharp incense of fir trees through an open window. Cool late spring air was flowing down off Grouse Mountain. In just a minute or two, clouds appeared outside the same window and seemed to touch into the front room. Then the sound of rain beginning to fall into trees and onto shingles and into eavestroughs came into my ears; it hypnotized me. The next day, I was struck by the down-to-earth and outright kind manner of person after person in everyday situations. So I think after you’ve been away from your home and come back to it, yes, you see it differently, more clearly. You see the place more for what it is. You also get a renewed sense of the mystery of where you come from. I feel these days that a person might be equipped to appreciate the qualities of mystery and magic of the place he comes from better than any other place precisely because he comes from that place.

I love that idea of exploring (traveling into?) the mystery of the place where one comes from. Do you consider your poems about North Vancouver to be travel poems in their own way?

The source of the deepest dreams and of the end destinations of the most intense wanderlust is, for me, I’ve come to realize, the place beneath my feet. Two of my four immigrant grandparents were brought as young children to Vancouver and lived on the North Shore from early ages. When they grew up here, the area was far less populated, developed, and moneyed than it is now. Both of their families started out in shacks on what was then a wild shore and is now West Vancouver’s Ambleside Beach. I was born and grew up in North Vancouver, and although I’ve lived in a few other places, I’m still nothing if not a North Vancouver poet.

That interchange of sunlight and rain is an elemental conjuration; it incites a certain attention.

I’d say that a main permanent image within my brain folds is the prospect when you look west past the Lions Gate Bridge towards Georgia Strait: out there, the sun is shining brightly, and in North Vancouver it’s raining, so that the light is raying in through the rain. That prospect provokes what is for me the essence of travel: the dream of transformation and of creativity itself. That interchange of sunlight and rain is an elemental conjuration; it incites a certain attention. So, ironically, in my case, here as nowhere else I have a chance to enact the transformation that once seemed available only in faraway settings.

Do you see any parallels in your time away from North Vancouver and subsequent return, and your return to consideration of your childhood (and your father-son relationship) through having children of your own? Are they inevitably intertwined?

Images of my father figured dramatically in my memory and imagination before I had kids; the father-son relationship as a theme captured me from the beginnings of my attempts to write poems. Still, it seems inevitable that when you have kids you rediscover bits and pieces of your own childhood. My personal father-son images and narratives intensified for a while. Do you know that Sylvia Plath poem, “For a Fatherless Son”? She says in it, “You will be aware of an absence, presently, / Growing beside you, like a tree, / A death tree, colour gone…” It was certainly like that for me.

I think my small kids became something of a composite muse for me for a couple of years. I figure this might well have been a function of re-experiencing my place of origin through their eyes, and at the same time standing in that place not as a fatherless child but rather in the form of their father. In some ways, I’ve found that the parallels between my relationships past and present and the particular place where I grew up amount to an offer of transformation. The natural world of North Vancouver has been for me a kind of lesson in irrefutable creative realities. Life makes and remakes us, parent, child again, parent, as it continually forces us to re-align our personal woes in a scheme of things that is grave and joyous, and ultimately impersonal. Oddly enough, I feel, this scheme of things is inside every person: a person we all have in common, as close as the jugular vein, a kind of person of persons, a person in the heart no bigger than a thumb.

That absence beside me: yes I have grown in my writing and my life similarly to what Plath suggests, having lost my own father as a child. Carrying his name and wondering what it carries inside it.

One fascinating theme that runs through The Broken Face is the importance (or unimportance) of names, especially the European and Indigenous place names of North Vancouver. In the poem “North Vancouver” you write: “The more years that go by, the more names I have learned leave me, the more the number of names I would like to learn increases—and I learn Chay-chil-whoak Creek, Kwa-hul-cha Creek, and then these names too gather like mist, then move off and away like mist.”

And later, in “Aftermath”:

It is called Wagg Creek, but that name

is not the name given to it

long before anyone named Wagg

existed, or his ancestors

dreamt of this far place.

You also note in your conversation with Phoebe Wang in What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation that it’s been “exciting” to learn Squamish names.

I’m conscious of the fact that at the same time as you were learning anew to name the places around you, you were also raising your aforementioned young children: naming them and providing for them the names of everything in their world. Did these two processes fuel one another in any way, and did they bring you to think about names, or words, or poems, in a different way?

I’ve always been fascinated by names and naming, and by names and namelessness. Like a lot of people, I suppose I’m in a kind of thrall to words (“In the beginning was the word”!). Do you know the A.M. Klein masterpiece, “Portrait of the Poet as Landscape”? It has that extraordinary bit at the end: “Look, he is / the nth Adam taking a green inventory / in world but scarcely uttered, naming, praising, / the flowering fiats in the meadow, the / syllabled fur, stars aspirate, the pollen / whose sweet collision sounds eternally. / For to praise / the world – he, solitary man – is breath / to him.” I love this poem. There are also one or two pieces by Gwendolyn McEwen in which she sings about names and naming; I love them as well. Both of these poets are aware of mystical concepts associated with naming; it seems that they know deeply how the act of naming is infused with strange power.

The English-language names I learned as a child for the creeks and rivers I grew up around (usually the surnames of colonial men who came to “own” land alongside these waters) always seemed to me to be off; they didn’t fit my experience.

I’m interested in concepts to do with names and naming (“the ineffable name” of God in Jewish mysticism would be the prime example), and how the “real” names of all things must necessarily be secret, unknown. My interest in the original language of the place where I was born and now live (and where I’ve chosen to raise young children) comes from wanting to know what the First Peoples here call the place, and how they relate themselves through that calling with specific natural locales and phenomena. The English-language names I learned as a child for the creeks and rivers I grew up around (usually the surnames of colonial men who came to “own” land alongside these waters) always seemed to me to be off; they didn’t fit my experience. Although my first language is English, and my kids’ language is English too, the language doesn’t necessarily work very well for any authentic appreciation of our surroundings.

I suppose I’d like my kids to be a positive part of their natural environment. The languages initiated in this particular area thousands of years ago: they seem essential. At the same time, as I say in the poem you mention (“North Vancouver”), I feel the names we use for things, English or Squamish or Halkomelem, ultimately “move off and away like mist”; all names vanish into the unknown name of names.

The Klein is new to me. Thank you for the introduction!

Continuing in our consideration of the local: you started your publishing career working with presses in other parts of the country, before finding a home at a BC press: Harbour Publishing (starting with House Built of Rain in 2003), who have published all your books since (with the exception of The Hundred Lives). You also publish chapbooks with the Alfred Gustav Press, based right near you in North Vancouver. Do you see a connection between your movement toward writing more and more “locally” with your working increasingly with BC-based presses?

With my first couple of collections, I was simply enormously happy to be published in book form. It didn’t matter to me who the publisher was or where the press was located. At the same time, I had the dream as a “poet” to have a relationship with a BC publisher and be able to send manuscripts to that publisher and realistically hope for a non-slush-pile response. Harbour Publishing was always my goal. I’d read all the Harbour poets and many of the press’s other writers. I bought Harbour books on hiking, local history, etc. I found I admired Howard White as a maverick publisher and writer. So when I got a book published by Harbour, it felt right to me; I stopped looking elsewhere. The Hundred Lives was different sort of book for me content-wise. I didn’t see it as a Harbour book; that was why I published it with Quattro Books in Toronto.

As I find myself writing more and more about my immediate locale (even, paradoxically, as I might be trying to widen my focus on certain levels), yes, it seems more and more appropriate to me to publish with a BC press. Regarding the Alfred Gustav Press: that was a pleasure for me because it’s a North Vancouver press and all of the poems I included in the little chapbooks I published with that press were quite specifically related to North Vancouver.

Your recent book publications have come in two flurries: first, four book in six years (2000–2006) and now three books in five years (2013–2018). Between them there was a seven year gap. I suspect at least part of that public “silence” had to do with the two children who play a prominent role in the poetry in your recent books. Could you speak about the gap? Did you stop or slow your writing output at that point, or did you continue on as always and simply not publish? How, if at all, did that time away from publishing change how you thought about your writing? Your views on book publishing?

If poetry is “stored magic” as Robert Graves said, it’s definitely a magic

that’s difficult to produce. Language for me is relentlessly alluring as it is intractable; it’s my friend the enemy.

I’ve filled notebooks since I was a teenager—even when I’ve been occupied with more than full-time work or, as in the past decade, with bringing up kids in addition to income-getting. But, yes, I’ve had a chequered publication history. I think it’s mostly because I’ve never been interested in a “career” in poetry, in which I proceeded from a “debut” to this or that as in a thought-out marketing campaign. In any case, I haven’t exerted myself to have books appear at regular intervals; I’ve tried to get published when it felt right to me to put a frame around a bulk of poems. I’ve been excited to see my poems between covers, that’s for sure!

There’s a W.B. Yeats poem where Yeats says, “I have gone about the house, gone up and down / As a man does when who has published a new book…” I’ve felt that! It’s also marvelous for me simply to blacken pages and tinker with whatever I see there a day or a week or a year or more later. And that’s the deeper pleasure as well as the necessity for me: the act of writing.

Through all your years of tinkering with blackened pages it feels like you’ve worked your writing more and more toward a particular sound and shape I can quickly identify as a “Russell Thornton” poem. I can’t say I fully understand the ingredients that go into a “Russell Thornton” poem, though some of them would be your word choices (conversational, shorter), your rhythm (steady, iamb-heavy, sometimes almost chant-like), your use of long sentences, and the overall length of your poems (usually more than one page, less than two).

Do you feel like, after decades of poem-making, you carry around a bit of a template for a “Russell Thornton” poem in the back of your mind? Or are you starting from scratch every time? Has it become easier for you to write a poem over the years, or more challenging, and why do you think that is?

I’m starting from scratch every time, no question. I do hear a certain set of sounds in my head—and I think these sounds may belong to a poem that I’d like to write—but I haven’t ever managed to log the sounds properly on the page. My idea is to keep trying. If poetry is “stored magic” as Robert Graves said, it’s definitely a magic that’s difficult to produce. Language for me is relentlessly alluring as it is intractable; it’s my friend the enemy.

In your recent books, I’ve noticed a move away from direct references (via epigraphs, allusions, etc.) to the work of other poets and writers. Only one poem in The Broken Face features an epigraph (down from six in Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain). And the epigraphs for both books, which in many collections are quotes from other writers, are small introductory poems you wrote yourself. By comparison, you quote Blake to open The Human Shore and Rilke in The Hundred Lives.

This contrasts with your writing-about-poetry, including this interview, where you’ve already quoted so many poets! Is this reduction of direct references within your poems a conscious choice of yours? If so, is it connected in any way to the ever-more-personal themes (your family, your city, your neighbours) you circle in The Broken Face? Clearing out the voices so you can focus in on what matters most deeply to you?

The way I see it, we’re searchers; we’re always searching for what is searching for us.

I think poets breathe the air of the poets alive around them as well as the poets that have come before. It’s inevitable that any given poet’s pieces are filled with allusions, direct and obvious or subtle and half-hidden. I’d say that in a way all poets are part and parcel of a single composite anonymous poet. I think the irony is that this “poet” is alone. And I think the natural state of individual mortal poets both is and isn’t one of aloneness. Most monumental artistic human expression is for me a cry or wail or howl of aloneness, an address to whatever is out there, or in there—and is other, totally other than ourselves. I think the creative cry announces our essential aloneness. But it’s an ecstatic aloneness. Love, imagination, can give us flashes of an experience of not being alone, and can create for us sites of recognition: of recognition of another person, of invisible realities, of the levels of love. But even in those flashes, what we’re aware of is aloneness infinitely wider than our own. That other aloneness is lonely for us, and we’re lonely for it.

And so, the way I see it, we’re searchers; we’re always searching for what is searching for us. The instant we’re not alone, however—the instant we find and are found—we’re not any longer what we were, we’re unfamiliar to ourselves, we’re someone or something else, other, we’re not there. I don’t think I’ve ever written poems that aren’t personal; the difference between The Broken Face and other books I’ve produced might be in the presence of children and the crux to do with “crime”: in the particular play of the paradox of being alone and not alone.

One poem in The Broken Face, “The Wound”, embraces your idea of the “single composite anonymous poet,” working 19 separate quotations into its lines (a third of the poem’s content). The quotes are a mix between lines from poets in the English literary canon and Haida storytellers. “The Wound” bucks the book’s quote-free trend in a big way. Its subject matter (The Great Pacific Garbage Patch) and its length (four pages) also serve to make the poem feel like a bit of an outlier.

What spurred you to write “The Wound”? How do you want it to function within a larger book that in many ways is pulling in different directions? Is having “outlier” poems (thematically, stylistically) which widen the range of a book important to you as a writer? As a reader?

I meant this poem as an elaboration of the “crime” theme in The Broken Face. The “wound” is the wound of humanity’s separation from the natural world brought about by consciousness. It’s also the wound humanity makes in the natural world. The “crime scene tape” that surrounds the Pacific Ocean is humanity guilty of self-consciousness and of creating a hell on Earth. At the same time, humanity is represented by the voices of the poets I quote in the poem: the voices of the creative as opposed to destructive qualities and repercussions of consciousness. Yes, I wanted to carry very personal themes to the wider theatre of human community, enlisting the help of some of my favourite poets; it seemed appropriate to me on an imaginative level.

Speaking of the wider theatre, your 2014 collection The Hundred Lives took us halfway across the planet and also back through your writing catalogue. Based around your time living in Greece and your writing inspired by Biblical sources (most notably The Song of Songs, which you’ve elsewhere called your favourite poem), many of the poems were drawn from each of your preceding five books, and a few were originally published (in magazines, etc.) as far back as 1997. It must have been fascinating to go back through your old poems and assemble them in this way.

What did you learn about your development as a writer in the process? Did that experience (including the post-publication experience of its being shortlisted for the Griffin Prize) influence your thinking on what you might do next, in ways we might detect in The Broken Face?

Yes, for almost a half of The Hundred Lives I put together poems from previous volumes (going all the way back to The Fifth Window, 2000) that were set specifically in Greece, or, in the case of the handful of approximate sonnets called “Lazarus’ Songs to Mary Magdalene,” set in a general Mediterranean/Middle Eastern world. In the larger part of the book, I brought together some selections from an unpublished manuscript that I wrote a few years ago based on The Song of Songs. I spent two years translating The Song of Songs, and as I did that, I found I was writing pieces in response to what I was discovering about the resonances of the text. It was exciting for me; I felt I was confirming intuitions I’d had about connections between the erotic and the divine, and between these and imagination. For the latter part of that book, I brought together some overtly personal poems that hadn’t fit in any of my previous manuscripts but seemed to fit in this one.

I was a bit hesitant to assemble a manuscript clearly concerned with “spiritual” and “erotic” themes, but once I had the book in my hands I was pleased; I figured I’d managed a certain fidelity to myself. After I put together The Hundred Lives, I became more aware than before that I had a couple of seemingly quite different chief poetic impulses. I see myself as a simple describer of nature, a writer of short narratives, a poet of memory and place—yet I’m also extremely interested in the metaphysical. I’d say that my experience with The Hundred Lives helped me to be more honest, and I see honesty as crucial in trying to allow whatever I write to touch upon—as much as possible—what concerns me as a reader and as a person.

As it happened, a couple of the poems that I included in The Hundred Lives gave me the license to try to come up with what are for me important strands of “part II” of Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain; the “condemned man” that I introduce in The Broken Face is an autobiographical move, but on a symbolic level I think the figure has an association with the Lazarus story. I’d like to explore how I might integrate and redeem this figure in a future book or group of poems in which I also manage the work of unifying varied poetic impulses. It’s an idea anyway!

And a good one! I look forward to reading those poems one day. Speaking of future writing plans, as a “big-time Canadian poet” have you ever felt the desire to do as “big-time Canadian poets” are supposed to do and write a novel (or short fiction, or…)? Or is your devotion to poetry unwavering?

The heightened, incantatory language of poetry never ceases to work its magic on me and make me want to try my hand.

I’ve written prose (short stories and memoir pieces that I’ve kept to myself) for brief periods when my poem writing flagged. When poems have started coming to me again, I’ve forgotten about prose. The heightened, incantatory language of poetry never ceases to work its magic on me and make me want to try my hand. I keep going back to wanting to participate in what I believe is poetry’s chant of the deepest desires. Having said this, I’ll admit that ideas for producing prose occur to me quite regularly. Maybe when I have more than 1.5-2.0 hours per weekday for writing (jobs! childcare!), I might set up scaffolding for a serious crack at that and see what I can come up with. It wouldn’t be out of any desire to “make it” as a Canadian writer; it would be because I felt like doing it. In any case, I’m still finding myself writing poems on a daily basis, and that’s fine with me!

Yes, it doesn’t get much luckier than that! I suppose that means we shouldn’t worry that another long publishing silence is on the horizon? If you have another book in the works, do you have a sense of how it might be different from the books that preceded it?

I tied a ribbon around a new manuscript towards the end of 2018. I’ll submit it to Harbour at some point, I guess. I’m calling it The Nothing Eye. I’m well into a subsequent manuscript, The Terrible Appearances (a title I’ve had hanging around in my head for a while now). In both of these books, I attend a lot more to what I’d call the metaphysical and mythological than I did in either of Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain or The Broken Face and maybe even more than I did in The Hundred Lives.

Russell Thornton is the author of The Hundred Lives (Quattro Books, 2014), shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize, and Birds, Metals, Stones & Rain (2013), shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award, the Raymond Souster Award, and the Dorothy Livesay BC Book Prize. His other titles include The Fifth Window, A Tunisian Notebook, House Built of Rain, The Human Shore, and his newest collection, The Broken Face (Harbour Publishing, 2018). He lives in North Vancouver.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best Canadian Poetry in English (Biblioasis, 2019). In 2015, Rob received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for the Literary Arts, as an emerging artist. He lives in Port Moody, BC with his wife and son.

Read more 2019 National Poetry Month features here.