The following interview is part one of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2019. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Pride – Dina Del Bucchia

Sometimes it seems easier for every person close to me to be gone, than for

them to have to put up with me as a disappointment. Pressure when I think

about a family gathering, attempts to careen conversation topics into things

I excel at. Avoid eye contact when the future is brought up. Unless it’s

theoretical: talk of spaceships, technological innovations, our bodies

transcending shape and space. Humans considering retirement, balancing

accounts. Who will take care of my parents when I’m working seven

minimum-wage jobs? If we can preserve brains by then, I will sit in virtual

reality and hold their hands, make them laugh with stories about my life.

Continue to avoid eye contact, wherever their eyes might be out in space. I

don’t need them to be proud of me, cheers and air horns. I just need to feel

them pull away from their own worry. Hot chest, hands, eyes, feet. Mine

still firmly rooted on the earth.

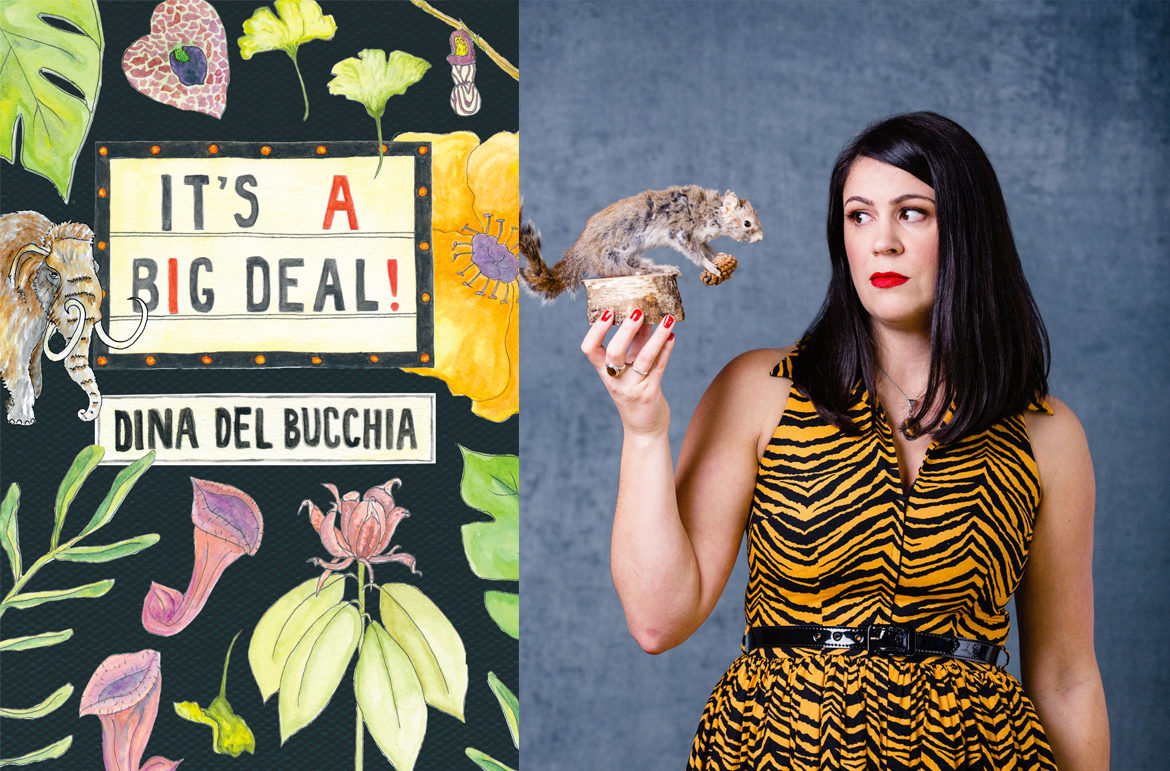

Reprinted with permission from It’s a Big Deal by Dina Del Bucchia (Talonbooks, 2019).

Rob Taylor: Your new poetry collection, It’s a Big Deal! (Talonbooks), opens with the instruction “Read Marketing for Dummies. And then set it on fire because you are no dummy!” From there the book goes on to channel and ridicule a wide range of imperative language, from advertisting, to corporate-speak, to self-help books, to our own internal monologues (all the ways we are told, and tell ourselves, what to do). In this way it mirrors the self-help poems in your debut collection Coping with Emotions and Otters (Talonbooks, 2013). What draws you to explore these types of voices (and power dynamics) in your poems? Do you think your years of working in retail have shaped your thoughts around giving and receiving orders, including around what to consume?

Dina Del Bucchia: You’ve tied in so many things about my life and writing in this one question! I definitely see this collection as a companion to Coping with Emotions and Otters.

In some ways everyone is a writer because there is content everywhere.

I think what draws me to these voices is a lifetime of experiencing being on the lower end of a retail food chain. It’s also in seeing people buy those self-help books, seeing the trends that appear around how we are supposed to better ourselves, watching how those trends influence television and film, and fashion, and food. Everything is connected now because it can be monetized, and influencer-ized, and the gig economy is here to suggest we can simply add “#ad” to a post and that is how people are paid. But it’s not really true. Native advertising is wild. In some ways, everyone is a writer because there is content everywhere. Is this what most poets are thinking about? Instagram influencers and LinkedIn? Sometimes I wonder if I should write a damn poem about some flowers in a field or something.

Ha! I envision a flower from time to time, crushed under the foot of a mammoth or something.

Speaking of Coping With Emotions and Otters, that book shared a similar structure to this one: opening with the more self-helpy poems and ending with furry animals (in that case, otters, in this case, extinct megafauna like the aforementioned mammoth). You also bring the two books together by ending It’s a Big Deal! with a poem about the extinct Giant Otter (Siamogale melilutra – how excited were you when you learned about them?).

In between those two books, you put out two other poetry collections—Blind Items and Rom Com (with Daniel Zomparelli)—which seemed more singular in focus. Do you consider this book to be more in keeping with Otters? A sort of sequel? Do you think of it as a general collection, or as unified in a way that matches your last couple books?

I remember reading about the Giant Otter when remains were discovered in 2017 and knowing that I was obviously going to write about it and also that it would be the poem to end the book. And I do think It’s A Big Deal is a sequel of sorts, certainly a continued conversation with some of the poems and ideas in Otters.

I am probably typical, in that, like most writers, I have certain interests that don’t just creep into my work, but live there full time. For me those are contemporary culture, pop culture, and how we all connect or don’t connect to it, how it influences our lives, how we absorb or consume or reject it.

Whether I’m writing about romantic comedies or celebrities or megafauna it’s all coming from a place of interest and interrogation (or obsession) that feels the same to me. A driving force. I think a lot in terms of persona and voice. Writing megafauna and writing about celebrities felt so similar to me, in unpacking who they are, what they mean to the speaker of the poem, digging for them, finding truths, and also making assumptions and making things up.

So yeah, I do think overall there is much overlap between all of the books, and to me the otters and megafauna and celebrities are all on the same level of fame.

In addition to sharing a certain constellation of “obsessions,” your books, or sections therein, are often tied to one theme or written in one style (“projects,” as someone writing a grant application might call them). In It’s a Big Deal!, the section “Tips” includes poems which comment on Marketing, Dating, Beauty, etc. (and are titled accordingly), while titles in the “Big Ideas” section include “War,” “Peace,” “Religion,” “Politics,” etc. And the aforementioned last section is dedicated to giant dead animals (“Megafauna”).

This made me curious about the role of structure in your writing life. Do you usually write toward a particular project or theme? Or do you just write whatever, and the categorizing comes later? Do you set aside particular times in the day/week to write, or just write when it comes to you?

I’ve barely worked on anything, aside from revising and editing this book, in over a year. So, right now is the first time I haven’t had overlapping writing projects. And it’s very odd. And uncomfortable, but also fine. Without knowing what I’m going to work on next I’ve had a hard time writing at all. My other books were all written over top of each other, one while taking a break from another. So now I’m like, um…

When I’m in the early stages of writing I let the pace be whatever it is. The organizational stuff, the scheduling for me, comes later when I’m revising and working through drafts. I’m pretty obsessive and excitable, so often the initial writing is frenzied, even if it’s just a few lines or the nugget of a story. If I stop being interested in something I stop, and maybe it becomes interesting again, maybe it doesn’t, but it’s always right there waiting for me, like a pop ballad.

I think I’ve let my life and work take up a lot of my time, and that hasn’t left room for writing. I’ve taken on a lot and I don’t regret the things I’m doing, but I might finally have to confront the reality of what my writing time will look like once I decide to start doing that again. And writing for me has escapist qualities, so I do miss it for a lot of reasons. I want to live in the heads of other people for a while.

Though not people, you did spend a bunch of this book living in the heads of giant dead animals. The “megafauna” are delightful, but what’s up with them? At first they seem totally out of place in a book about the modern realities of urban life, but soon enough these ground sloths and mastadons and cave lions start bleeding into our present moment. They star in reality TV shows and Jimmy Kimmel mean tweets, and are surrounded by brunch, bronies, and global warming (they’re on the “same level of fame,” as you suggested earlier).

What got you thinking about extinct megafauna? When did you get the idea to bring them into conversation with the rest of the poems in the book, and how do you think they influence the overall feeling (dare I say “message”) of the book?

When my first book came out I was invited to a poetry festival in Whitehorse. While I was there I went to the Beringia Interpretive Centre and was blown away by the vast array of giant animals that used to be on this planet. We hear so much about dinosaurs, but the extinct megafauna aren’t quite as popular, so I wanted to explore them. They were also alive at the same time as humans, some were even food, so it had me thinking, “What is our relationship to these extinct animals?” I thought about how to interpret them through a modern lens; to look at them the way we do with cute animal videos online. That also connects to my first book, which had poems written about otters that became YouTube famous. I don’t have a lot of tricks up my sleeve.

Looking at what is no longer alive is an interesting way to look at the world now.

Looking at what is no longer alive is an interesting way to look at the world now. Why do some things, like dinosaurs for example, hold such cultural capital, but a giant ground sloth doesn’t? What holds value, what do we remember, what is important, what is a big deal? The whole book hinged on that one poem’s title, which became the book’s title and, I hope, influenced all the sections and poems. Initially the book was just megafauna and the “Talk it Out” section. The other two sections were things I was sort of working on but realized could connect once that title took over.

It’s amazing how finding that right title and “angle” for looking at a book can snap everything into place, isn’t it? You joke about only having so many tricks up your sleeve, but I think what we’re really seeing is your deep awareness of the undercurrents that connect your poems into a book. You know how to weave everything together, both in theme and image.

One such theme in It’s a Big Deal! revolves around sarcastic or absurd, sometimes justifiably embittered, responses to the daunting economic realities of the world. It’s tough to get by for under-40s (and artists, to boot) anywhere in the world right now, but particularly in Vancouver. To what extent did the near-impossibility of making it in this city shape its content and tone?

I am almost not under-40 and I think this is reflected in the final revisions of this book. How will I retire, let alone survive the next decade? I want to question the larger economic realities, because, frankly, they’re garbage. Those systems are trash and so many people suffer because of them. I was looking at my own concerns, and those of friends, and others I see in the city.

Living somewhere that is obsessed with self-help, improvement, wellness, and appropriative healing practices; that wants to be both a weed-inhaling Vangroovy pseudo-hippie enclave and a completely corrupt capitalist real estate hellscape, is both terrifying and hilarious. It’s all about money translating to wellness, and self-improvement. And people here want to act like they’re so chill and accepting, but they’re also super fatphobic for example, which is extremely ironic and gross. It’s like a part of the city is saying, “Accept who you are, unless you’re any of these things that we don’t like and think are unhealthy. Please enjoy this framed self-affirming print though, it costs $90.” It’s a get off our lawn vibe, and only rich people have lawns.

Few people have done more than yourself to provide a platform for up-and-coming Vancouver writers. That work includes being senior editor at Poetry is Dead, co-host of the Can’t Lit podcast, and coordinator of the Real Vancouver Writers Series. You are vital to the success of Vancouver’s cultural community and yet, as mentioned above, the city sends a “get off our lawn” message to artists with every foreclosed arts space and renoviction. Which city do you feel you’re living in most often, the city you are a part of making, or the “corrupt capitalist real estate hellscape” that the global economy is busily demolishing-into-being? Are they inextricably one and the same?

So many people are doing work in the literary scene here, I just happen to be loud and selfie-loving and bright-lipstick clad. Visible. Audible. It doesn’t mean I don’t do a lot of work, but I know so many are out there doing so much. I am grateful to many, including Ben Rawluk and Daniel Zomparelli at Poetry is Dead, Jen Sookfong Lee at Can’t Lit, and Sean Cranbury and the whole team and board at Real Vancouver. I hope people are going to Growing Room and Indigenous Brilliance and Fine.

I have the energy (most of the time) and I want to create the events, publications, and podcasts I’d like to see in the city. That means putting in the time and calling on the best people and listening to them, especially when they are telling us about new voices or people who are doing exciting things. I am bad at being quiet and alone, so I like to do things that involve bringing people together—parties that are hopefully amenable to the mostly introverted and anxious folks in the literary sphere.

This city is rough. The good and the bad are one and the same and I can’t see it another way. The city wants us to make their coffees in the business district and not have homes, but we’re always finding funding or pockets of space for art. I am hopeful on some level that we can all survive here—artists, people in the service industry, single parents, disabled people, etc.—and that the city won’t turn us all out. Occupy Shaughnessy, burn something down, build a barge out of craft beer cans and dock it in front of the fanciest yachts.

Ha! Ok, that leads well into my next question. So many of these poems are damn funny (example: “How do you make your household sexier? The answer is to masturbate in the linen closet”). How often do you get to say that about either A) a Canadian book or B) a book of poetry, let alone an A-B combination?

Why funny poems, Dina? How do they do their work differently from “serious” poems? Does a joke, dropped into an otherwise serious poem, somehow change the molecular structure of the whole thing? Or can it just be a laugh for a laugh’s sake?

Laughing is great and people like doing it. The end.

As a writer I think part of craft is knowing what you want your work to do, and for me a part of that is I want it to entertain. Books are entertainment. Books are not these dour things that teach us about stuff, though yes they do that and I hope my work does that too, but people do read as part of their leisure life. I know, this may seem shocking and strange.

I think the emotionality of a poem is important whether the tone is more serious or more humorous. Sometimes you have a really funny line, and it is integral to the theme of the poem, and that is the greatest moment. All the connections are there. Similar to writing that is serious in tone, you want all the elements to be there: for the work to feel complete and full and the writing to be sharp. For me, humour is one of those elements. But sometimes, sure, you drop a one-liner in for a fun time, and that’s great too. All writers have failed to kill some of their “darlings” and sometimes mine are fart jokes or quips.

You teach comedic writing at UBC. Who are some of your favourite comedic poets to introduce your students to?

I don’t talk about poetry much in class at all, but if I am asked (I am not) I do I often point to people like beni xiao, Kathryn Mockler, Gary Barwin, Tenille Campbell, Jennica Harper, and Daniel Zomparelli, of course. This is just off the top of my head. There are so many funny poets. Please contact me for more information.

Speaking of all the great writers out there, in the acknowledgments or It’s a Big Deal! you thank your writing group, with which you’ve been working for almost 15 years. That’s amazing! What role has that group played in your development as a writer? In what ways has it functioned differently from/similarly to your more formalized education in Creative Writing at UBC?

First, I need to say that somehow in the final proofs one of the members of my writing group was left out. And he is the best. Thanks John Vigna! He deserves to be acknowledged.

I was very much a baby writer when I joined the group. I graduated from undergrad in 2002 and joined this group in 2004. After a few members left and others joined we’ve been almost the same group since the fall of 2004. Everyone has different experience, which is crucial. Listening to others talk about their process of revision, the ways they approach story or character, has been amazing to be around.

Unlike a workshop, we don’t read the work ahead of time and then have prepared comments, but read to each other and discuss from there. Coming from that workshop style of sitting and not speaking it was refreshing to enter a space with people you trust and respect. We’re able to have conversations about problems in our work, to consider options, and to ask questions about what others have done and what suggestions they might have. Also, we get to celebrate our successes, discuss disappointments, and talk about the community in general. Formal workshops are great, and I got some great stuff from them, but conversations are so integral, to me anyway, to learning and growing as a writer.

Weird little structure question: all your poetry books are almost the same length! (110, 112, 128 and 117 pages, by my count—the longest being your co-authored book with Daniel.) That is a good 30 pages longer than the average poetry book, so it’s hard to believe it’s a coincidence. What draws you to that length? Will you ever come out with a Canada-Council-minimum 48 page book, or are those too weak and puny for you?

I don’t exactly know why my books are this long, but I guess being a verbose loudmouth translates into text.

I would love to write a sweet little chapbook. I mean, tonally it would probably be aggressive like all my other books, but short in length. It would be cute, in stature. I don’t exactly know why my books are this long, but I guess being a verbose loudmouth translates into text. I think because I am often obsessive about concept and subject I go a little overboard. I have a lot to say. I’m not against shorter books. I’d love to write a short novel, then I could be like, “Look at this novel I wrote!”

Small is not weak or puny! I am just over the top.

It’s a Big Deal! is your third book with Talonbooks, who also published your debut. Could you speak a bit about working with them, and the role that long-term relationship has played in your development as a writer?

Firstly, they are really open in communication when it comes to administrative things, and as I’ve developed as a writer I’ve found that relationships that make those things easier are, ahem, a big deal.

Secondly, I have had such great editing experiences with Rom Com and It’s a Big Deal! Talon has been great to work with and Sachiko Murakami and Nikki Reimer are amazing editors. The editing work Daniel and I did on Rom Com was obviously slightly more complicated with two writers, and yet it was such an incredible experience. And Talon were fully on board for the paper dolls of Daniel and myself in Rom Com, which to this day is a life dream fulfilled.

Talon also really made me feel like my ideas were good! Knowing I can bring ideas to them is great. It makes me want to not retire from writing, even though I joke about it constantly right now. Most of my books are somewhat ridiculous in concept or subject, but they were always interested. That alone is huge to me. Knowing I could continue to be funny, use my voice the way I wanted to, and try out my aesthetic-heavy cover ideas. What more could I ask for?

Want more Dina? Read her essay on how poetry complemented her fiction.

Dina Del Bucchia is the author of the short-story collection Don’t Tell Me What to Do (Arsenal Pulp Press) and four collections of poetry: It’s a Big Deal!, Coping with Emotions and Otters, Blind Items, and Rom Com, the latter written with Daniel Zomparelli. She is an editor of Poetry Is Dead magazine, the artistic director of the Real Vancouver Writers’ Series, and a co-host of the podcast Can’t Lit with Jen Sookfong Lee. An otter and dress enthusiast, she lives on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations (Vancouver, BC).

Photo credit: Sarah Race Photography

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best Canadian Poetry in English (Biblioasis, 2019). In 2015, Rob received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for the Literary Arts, as an emerging artist. He lives in Port Moody, BC with his wife and son.

Read more 2019 National Poetry Month features here.