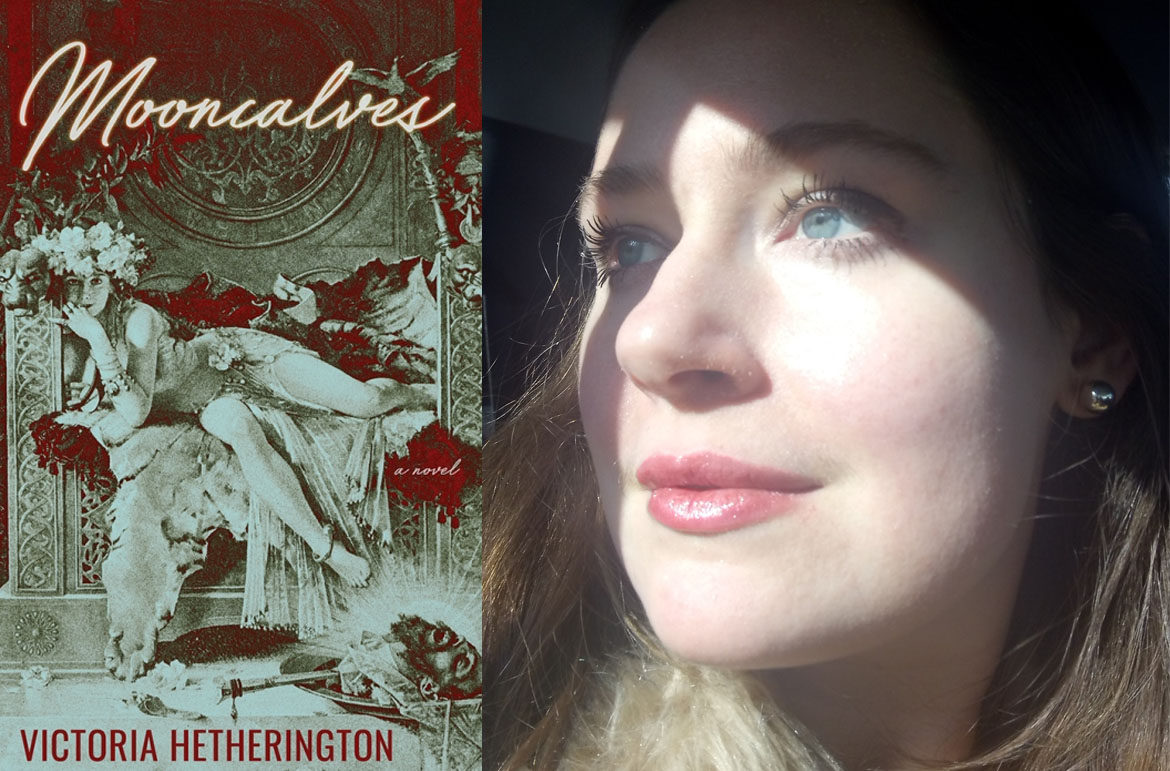

Mooncalves by Victoria Hetherington (Now Or Never Publishing) follows the bloody implosion of a cult in Sainte-Pétronille, Quebec. Sensing the impending dissolution of society by technological progress, the charismatic, utterly unhinged Joseph Reiser forms Walden, a collective of Luddite devotees—most still in their teens. But when a vicious act of sexual violence shatters the collective, devotee Erica Strickland barely escapes with her life.

Through its tale of buried crime in rural Quebec and the mechanism of cult leadership, Mooncalves explores the unshakable hold of first love, the warped influence of unchecked ambition and sexual obsession, and the uncomfortable gaze of the accumulating dead.

Mooncalves is your first novel, but you’ve written a lot of fiction already. When did you know what you were putting down on the page was going to be a full-fledged novel? Did it start in a different form?

Some people draft novels in incredible detail – charts and arrows and photos and highlighters and whiteboards – or so I imagine; writing is a pretty solitary thing – but for this book, a couple of ideas just sort of bumped together like raindrops on a spider web. I sat up in bed with a jolt, brushed all the crumbs off my quilt, and started scribbling.

Creepily enough, the book grew from a fascination with cult infiltrators like Dan Sullivan, who attempted to ‘deprogram’ cult members at great personal risk, and a realization that I would be an excellent ‘mark’ for a cult: I’m young, have incredibly low self-esteem, a deep pining to belong, and a shameful urge to impress others. Next, the characters sprouted forth like mushrooms: the recruits, the recruiters, the passionate nutcases with a ‘cause’ – after all, one doesn’t join a cult so much as a nonprofit group committed to a waste-free lifestyle or a yoga retreat, for example.

For the cult’s ‘cause,’ I looked to Silicon Valley: what better dark fairytale than the Singularity (a projected near-future point at which artificial intelligence will reach, and then rapidly outpace, human intelligence)? I drew on the cultural anxiety and adulation surrounding the Singularity, about which certain transhumanists like Ray Kurzweil are absolutely pumped for, and which others – like my fictive cult –

You drew on the experience of your mother for Mooncalves, correct?

When I hit a certain age—the age my mother was when she was approached by a cult—my mother told me about the experience. “It was weird,” she said, with a sort of distant inscrutability I’ve long found rather glamorous.

As we scraped egg yolk from plates and rinsed thick coffee grinds down the drain, she recalled the story in bits and pieces. Following a common recruitment procedure which involves young women targeting one or two people at a time – ‘flirty fishing,’ a term coined by Children of God cult – two such young women cast two modest shadows over my mother as she lay sunbathing as only a flower child of late 1970s Canada could: with prone, unafraid ecstasy, as if she could all but devour the nectar oozing through that little slice of summer she spent in rural Quebec.

She doesn’t remember what they said but remembers liking them, liking their story about a commune,

“Just to, to leave, to get out of the car?” I asked, amazed. “Just like that, on the 105?” This extremely narrow, treacherous Quebecois highway, snaking through blasted-out cliffs with massive trees and thimbleberry bushes impeding always like arterial plaque?

“I think so,” she said. “I think, yeah, I walked all the way home. I just knew.”

I dried the rest of the dishes on my own, under my own kind of shadow of something, which when articulated is roughly this: if it were me, I’d have joined them.

A decade later, I still believe this completely: I’d have been perfect for it. I’d have walked out of my life and disappeared. Over the next few years I read all the books I could, and assessed that the cult my mother had perhaps been approached by was the Ant Hill Kids, led by Roch Thériault, who fathered 26 children, conducted unnecessary ‘surgeries’ on his female devotees, forced each to sit on a stove to prove their devotion, and died from a shiv wound in prison. Read more, if you dare, but it’s not the kind of thing I’d read on a full stomach, or alone in the dark (though you might feel less alone as you read about it, in rather an unpleasant way).

The endorsements you’ve been getting are quite exciting. What do you hope readers will glean from Mooncalves?

I’m grateful these fantastic authors have taken the time to read the book, let alone say nice things about it!

This book required exhaustive, careful research: I learned a lot about the mechanism and history of cults, and about transhumanist projects of a post-singularity future – but I don’t presume to teach anybody anything. If there’s anything to be gleaned, I hope it’s rather in the vein of books by authors like Otessa Mosfeigh: her female characters are unrepentantly gross, flawed, and steely, a kind of female embodiment that challenges ideas of femininity that even women harbor, unexamined. But perhaps most importantly, I hope this book can be enjoyed; I hope people find it just as funny as it is horrific. Things get awful in my book, but it maintains a mile-wide streak of black humor throughout. What else can we do sometimes, but laugh?

People often write from personal experience as a rule. How much autobiography is there in Mooncalves?

Oh tons – too much. I mean I’ve never been to prison, sat in an autopsy, been a man, a robot, or a ghost, and so on, but, still – too much.

Your prose are very internal yet do not block out the pressures and dense detail of the world around your characters. How do you as a writer find this balance of intensities?

I presume we all live alongside a self-narrative that unspools as we go, rich as any movie. I do, you do, and my characters do as well. At the same time, I get to observe them at length and very much at a distance, and render them accordingly. I think how they think, and yet observe them as others would.

It’s like a lame, solipsistic kind of Cubism.

Are you looking forward to reading and touring your book?

From what I’ve seen, to be a writer is to nurture an ego that’s equal parts gigantic and frail; it’s about emerging from your introvert cave, reluctant and hungry, to feed at an ugly feast. So – yes! And also – god, no!

Victoria Hetherington is a Toronto-based author, poet, and visual artist, and her work has previously appeared in Joyland, Broken Pencil, The Puritan, This Recording, and The Hart House Review. Mooncalves (Now Or Never Publishing) is her debut novel.