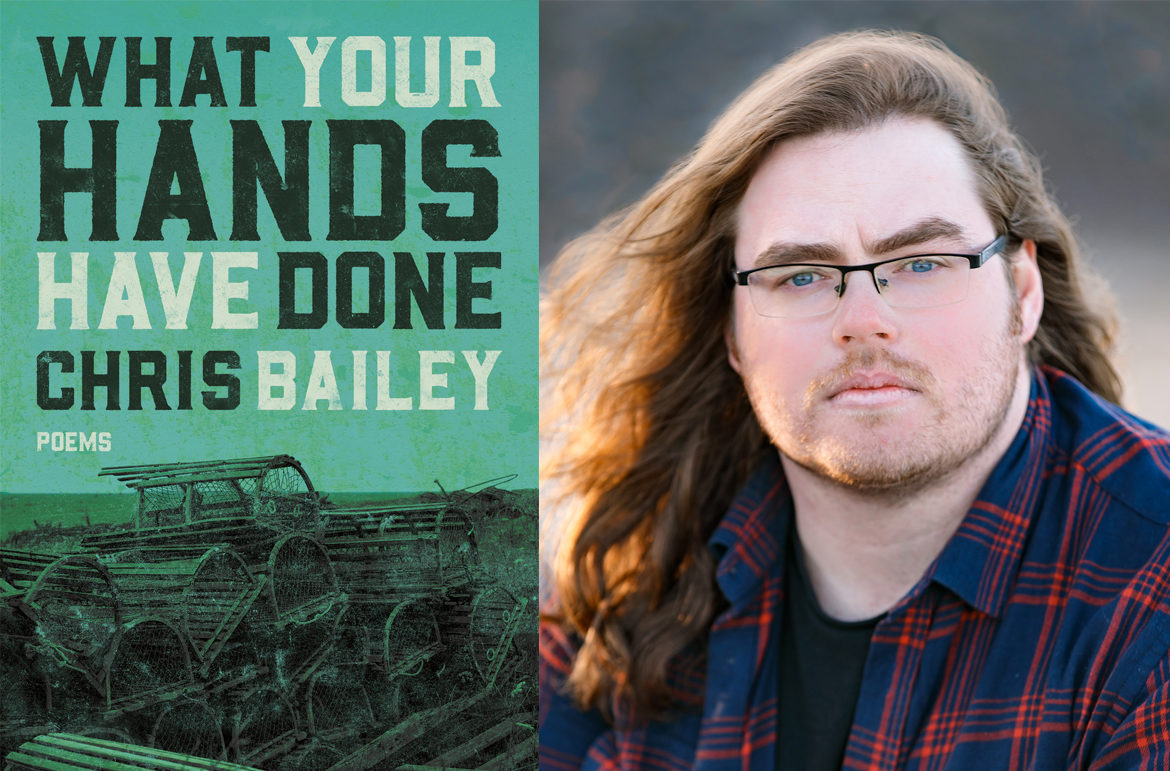

Chris Bailey‘s poetry collection, What Your Hands Have Done (Nightwood Editions), looks at how a life spent in a close-knit fishing family in rural Prince Edward Island marks a person. The book is rooted in PEI but moves from there to Toronto where the malaise of life proves to be unbound to the sameness of small-town days spent hauling gear on the Atlantic or toiling in rust-red potato fields.

The title of your debut collection is very compelling. Was it what you had in mind from the get go?

Originally, this was not my title. My intended title was Home is Just a Place to Hang Your Head, a line from the Warren Zevon song “Things to do in Denver When You’re Dead.”

“And LeRoy says there’s something you should know/ Not everybody has a place to go/ And home is just a place to hang your head/ And dream of things to do in Denver when you’re dead.”

I heard that line years ago and thought it was perfect for what I write about. The malaise of being here or there, of simply getting by, and the simple play on home being where you hang your hat. At my thesis defence, after I defended my thesis novel, my advisor, Dionne Brand asked me what my title was, and I told her, and she looked at me and said, “No. We need to talk about your title. It’s too long.” During the defence, she said she liked how I used my vernacular. She would point out a problem with the manuscript and I would say I’d fix it, and I would. I went home and flipped through the poetry book and frowned, and reread.

I got this title from the last few lines of a poem where the narrator’s father tells him he may have cancer, and the narrator breaks a cookie up and just stares a while at what his hands have done instead of speaking. I thought it worked on a couple levels, both with respect to work and sex, and so I wrote Dionne back the next day saying I fixed the title, that it was now What Your Hands Have Done, and she told me she loved it, and that it was mysterious and dangerous.

What excited you about this new experience? Publishing your debut collection and getting out there mixing it up with the public is obvious, but what in particular are you looking forward to the most?

Admittedly, I love to carouse. It’s my favourite part of leaving the house for things that don’t involve getting covered in scales and spawn and shit and guts. That I will get to go places I haven’t been to before, and talk to people I otherwise would not have met, and hear what they have to say about things. I’m looking forward to that for my own selfish reasons, namely, I love it so much.

In terms of the book, I’m excited for people to take a look at PEI in a way that’s free of Green Gables and isn’t really idyllic. Right now I’m fishing lobster and it’s cold as hell in the mornings, cold enough it actually hurts, and what people think of when I even discuss fishing or say “I fish,” is warm sun and families hard at work, but easy on each other, and life being sort of simpler than what they, themselves, may experience. I’m sort of demystifying, in a way, my occupation, my point of origin, and myself.

“I got this title from the last few lines of a poem where the narrator’s father tells him he may have cancer, and the narrator breaks a cookie up and just stares a while at what his hands have done instead of speaking.”

When did you begin working on What Your Hands Have Done? Was there anything strange that happened while working on the book?

This book is five years in the making. One of the poems got me into a creative writing workshop because I needed an elective and it looked like fun.

I’m also one of those people who, well, things just sort of happen, so it’s hard to pick a single strangest thing. There’s the PEI cab driver who got mad at me for recommending he read Elmore Leonard. The time I got to work with Lorna Crozier, and she called me a catch after a week of getting to know me and then seeing me read. How I ended up in a notorious slum in Toronto a couple months into my time there, and the only one who said anything to me about it was Dionne (this was after living on Toronto Island for a week, and then a month and a bit with a classmate and their family), and all the weird knocks on that door, beginning on my birthday when the cops knocked looking for the last tenant because she had called 9-1-1 and that was her last known address. That people in Hamilton stop me on the street to say how much they love my music or my band despite me not being able to play or sing a lick. How I found and lost a woman I loved due to, well, love tearing us apart. That I worked as a tour guide for a bit in Charlottetown on a half land half sea tour called “The Harbour Hippo” and it’s land-only counterpart “The Hippopotabus” whose tagline was “Hop on, go topless” since it was a double-decker, and my tips varied from a pamphlet on being a Born Again Christian, a subway cookie, peppermints from a guy’s pocket, and some sort of berry candy from an Asian country. I could go on. There are a lot of strange things (good, bad, and neither) that have happened, that I never would have expected. I mean, I never do. I can expand on any one of them.

And what do you hope readers will take away after reading your new book?

What I’m hoping most that they will glean is that they would like to buy another copy (or copies) for family and friends, and will want to buy the next one, too. Or buy me a meal or a drink when they see me. Other than that, I’m not sure. It depends on where they’re from in the country or the world, I guess. Canada is more than Toronto or the Tar Sands or a wilderness of trees. Eastern Canada is more than Newfoundland (where people outside of the Island tend to think I’m from because of my accent, I guess). PEI is more than Anne of Green Gables. That there’s a value in taking a look at the kind of life/lives depicted in the book. That there’s something to that work, that way of continuing on.

Chris Bailey is a fisherman and award-winning author from North Lake, Prince Edward Island. He has a MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph and is a past recipient of the Milton Acorn Award for poetry. His writing has appeared in UPEIArts Review, The Puritan’s Town Crier and on CBC Radio.