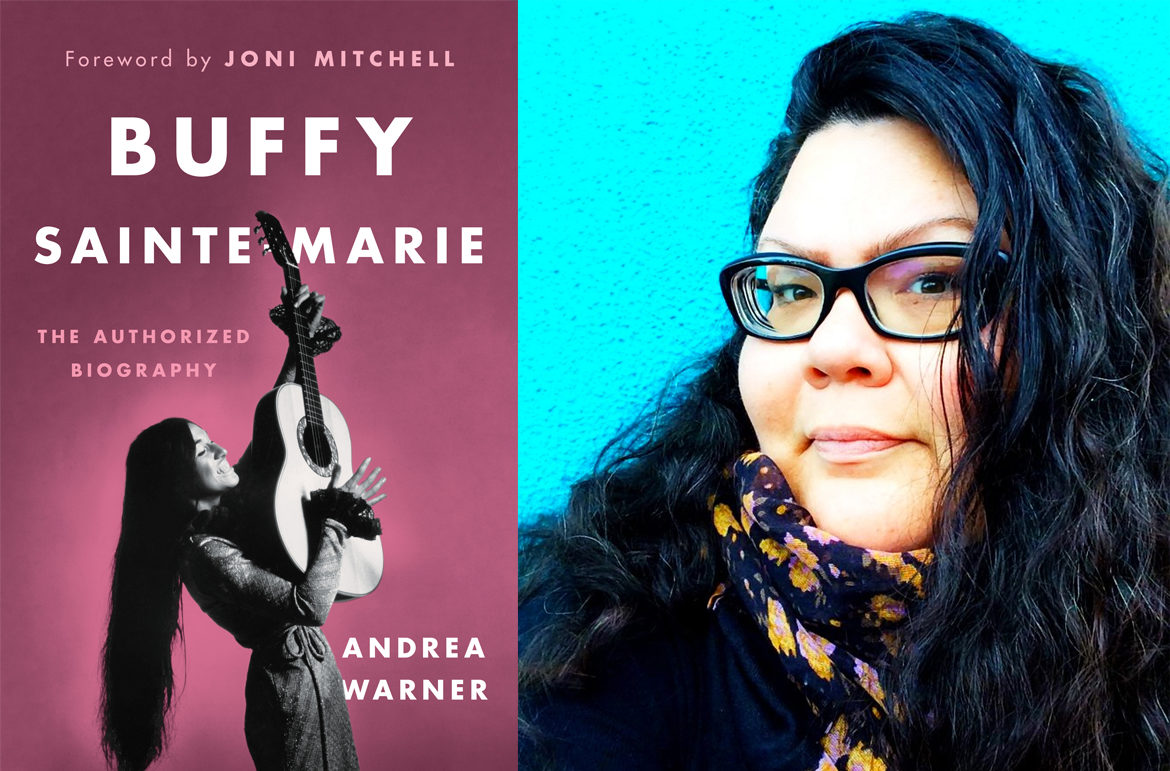

Music critic Andrea Warner drew from more than 60 hours of exclusive interviews with Cree singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie to create Sainte-Marie’s first and only authorized biography. Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography (Greystone Books) is a powerful, intimate look at the life of the beloved, trailblazing artist and everything that she has accomplished in her 77 years (and counting).

Read on for an endearing and charming conversation between the two artists.

Andrea Warner: So, why did you say yes to me and this book?

Buffy Sainte-Marie: I had read some of what you had written, including We Oughta Know. I knew your name and I think you interviewed me for CBC or you wrote something about an album for CBC.

AW: About Power in the Blood, and at the end of the phone call I was thinking, ‘Oh my God, I want to talk to you forever!’ and then suddenly you were like, ‘I don’t want to get off the phone.’

BSM: Okay there you go! I was so glad and when we first met, I just knew I was going to like you. We talked and listened to each other and I realized that as artists and people in this world we were interested in similar directions: up, down, sideways, around the corner. That we both had big heads—yes, big heads—that we weren’t trying to fit into somebody’s template. I felt that we’re both originals and that we appreciate uniqueness, originality, new thinking.

AW: From the beginning I think that you treated songwriting so differently than a lot of other people.

BSM: But see, other writers I think were trying to do that, too. I think they were doing it with a little bit different motivation. Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton and Bob Dylan in a way — but in a very special way — they were writing about the latest news. Phil and Tom, they used to pick up the newspaper and decide they were going to write a song a day about whatever’s in the headlines. But I’m not like that. I don’t think there’s anything against it, but I do it in a different way. I tend to write about what I feel strongly about in my heart but still isn’t being recognized by others. I’m not doing it just to get a hit related to whatever’s selling at the moment. A lot of us, when we’re young and in show business, that’s kind of what everybody’s trying to do. Everybody’s trying to get a hit. Everybody’s after the Get with a capital G. I wasn’t so much in it for the Get; I was in it a lot for the give.

AW: That’s a really beautiful way to phrase it. ‘You were in it for the give.’ I don’t think a lot of people really make art with that at the forefront of their motivations.

BSM: If you want to be effective, you’ve got to try real hard and I think most songwriters don’t try hard enough. As soon as they think that they can impress the kid down the street, they don’t go any farther. But let me see you sing that to a general audience and make just as much sense. You have to think about it more and you do have to think about it not only with your own heart but you have to try and think about it with that person’s heart, too. When you think you’re done, keep going, you’re not done.

AW: In the book we talk about your technological and digital experimentation and creation. Why do you think computers and technology come so easily to you?

BSM: I approached tech machines as new toys via music and art. There was no boss. If I had approached the same machines via taxes, business, uptight teachers, or military secrecy, I would not have had the passion, interest, or focus to keep me hot and motivated as I learned. And I was, and am, hot and motivated.

AW: What were the first pieces of art like that you made with your Macintosh?

BSM: In 1984 I started a digital illustration in MacPaint for a story I’d written called Forced to Dance. It was black and white, created completely in the Mac (no wet paints or photo scanning like we can do today). Apple didn’t yet have colour available to consumers, and I used MacPaint’s black and white pixels quite happily. Most artists were trying to “hide” or disguise the digital artifacts, trying to imitate oils, watercolours, photos, reality, other old school techniques associated with advertising art, but I deliberately did not try to blow away the pixelated edges of 1984.

AW: Are there comparable things about producing music digitally and producing paintings digitally? How are they similar and how are they different?

BSM: They are very much the same and if you already love and make both music and art, you’re going to love making digital music and art. The idea of saving multiple versions, as well as cut and paste, and taking elements of one song/image and using them in another way are the same techniques in music, art, and writing text. Very wonderful for any artist, especially a multi-tasker like me.

AW: Let’s talk about Sesame Street. What were the conversations that lead to the breastfeeding segment?

BSM: I was breastfeeding Cody on set anyway in whatever corner of the studio was available, and I asked (either Dulcie Singer or Lisa Simon) whether they wanted to include it and they said yes, and we did it.

AW: What was your favourite Sesame Street experience?

BSM: Too many to choose, but always anything I did with Carroll Spinney (who played Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch). But other Muppets, too — working with Grover to encourage his self-esteem is still a joy every time I watch it, he’s so endearing. But teaching The Count how to count in Cree was another highlight. To hear the numbers payuk, nisoo, nishtoo spoken with The Count’s Transylvanian accent still makes me laugh.

AW: A lot of people treat activism, it seems, as a sort of goal-oriented thing, but you are a lifelong activist. Can you talk a bit about how your activism has evolved?

BSM: From the time I was little I’ve been aware that everything’s always developing and that’s not a threat, that’s good news. I just think of Life as ever changing and evolving and I see that as thrilling. I’m not shocked by reversals in either direction, because I’m always expecting change. I see the human changes in a larger context of history, coming and going in waves like the seasons, like bees and termites, like saviours and cannibals: they’re always out there and I don’t take the current events of any one day personally. If you live in a wood house, every now and then you get termites. If you live among riches, you attract thieves. If you ignore termites and thieves in government, your house falls down. So I do what I can when I can, especially to alert audiences to red flags if I feel that they might be missing something because the news isn’t covering it.

AW: Sometimes activism can become a burden, particularly when people treat you as a spokesperson for something. But you’re so vital and youthful and have so much energy. How do you keep it up?

BSM: Regarding being a spokesperson, I don’t belong to any official groups (churches, political affiliations, etc.) so I don’t feel that kind of pressure. Every now and then some zealous fan would say something like ‘She’s our queen…’ but I always jump on that real quick. Indigenous people do not originate within the European pecking order. I never met an Indigenous king, or a duke or a prince, or any of that hierarchical fantasy wherein the royals are related to Jesus and you’re not. So I protest the queen label as something we should be trying to grow out of. That old European pecking order is obsolete and unhelpful. Stay calm and decolonize.

And as for your second question: zero alcohol and ballet.

AW: How does it feel to have just won a Juno for your newest record?

BSM: I’m so glad that Medicine Songs got this recognition, because of its content. Almost every song on it is a little treatise about something that I feel strongly about, something empowering or something to protest and try to make better. I’m giving my Juno statuette it to Elaine Bomberry in honour of her work in founding the Juno Music of Aboriginal Canada (Indigenous Music) category.

AW: What is important to you right now?

BSM: My mind is very conscious every day about human trafficking, and the history of the enslavement of Indigenous people in the world, which became institutionalized via the Doctrine of Discovery. I really hope and pray that Pope Francis might overturn it in my lifetime.

AW: What feels urgent to you right now? What are you most concerned about?

BSM: With regard to contemporary news and news figures, especially the right wing moving towards fascist policies, I’m concerned about possible backlash to much of the progress humanity has made in my lifetime. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale used to seem like science fiction. Now it seems like a caution. There’s always a new crop of five-year-olds—and a new crop of bozos. The good news: both can learn. The bad news: either can burn the house down if we citizens are not paying attention.

AW: What are you most hopeful about?

BSM: One of my mottos: The good news about the bad news is that more people know about it now. Although a lot of people are running around today as if the sky were falling for the first time, what I’m seeing is that average citizens are waking up to what’s been going on in the shadows since before the Old Testament. I see much of the hard-won transparency of today as indicative of good citizenship. “Good citizenship” sounds like a boring concept from grade six social studies but I don’t have a hipper word for it. Best advice: pay attention. If you see something, say something. And don’t be embarrassed: your participation can make the world better.

Join Andrea Warner to celebrate the launch of Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography at a free event at the Fox Cabaret on September 24, 2018. Andrea will be joined by special guests JB the First Lady and Angela Sterritt for live musical performances and readings, classic Buffy songs, a book signing, and more.

You can also catch Andrea Warner in conversation with Buffy Sainte-Marie at the Vancouver Writers Festival on Sunday, October 21.