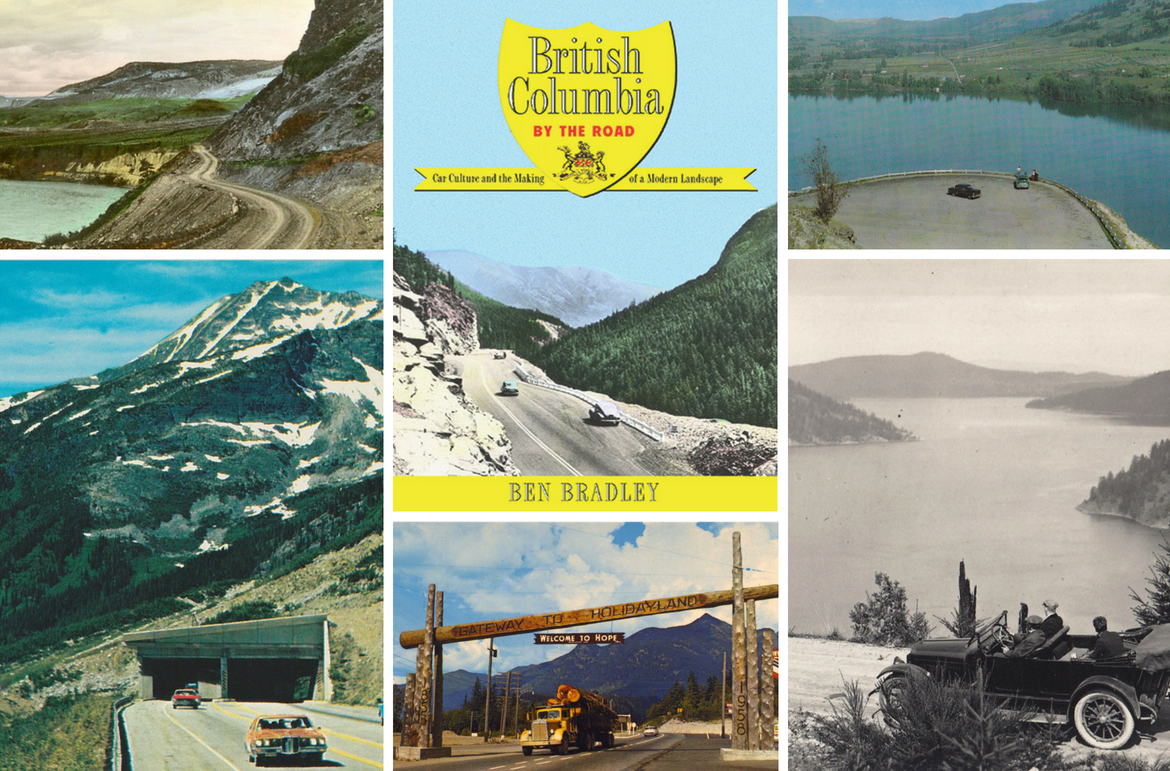

In British Columbia by the Road, Ben Bradley takes readers on an unprecedented journey through the history of roads, highways, and motoring in British Columbia’s Interior, a remote landscape composed of plateaus and interlocking valleys, soaring mountains, and treacherous passes.

School is out and for many, that means road trip season has arrived. Where to go? What route to take? What to see and do on the journey? British Columbians have been asking these questions for quite some time – it’s been 110 years since the mass-produced Ford Model T made car ownership and pleasure trips accessible to millions of Canadians and Americans.

Motoring in this province has a history of its own, even though we usually don’t think of it as part of the “bygone days” like passenger steam trains and horse-drawn stagecoaches. Roadside businesses that provided food, gas, and lodging have come and gone. Highways that were once main thoroughfares are now secondary routes. And a host of attractions and sights that were once popular with and familiar to the motoring public in BC are today largely forgotten. How many of these can you find traces of this summer?

Alexandra Bridge

Accessible by a short walk through Alexandra Bridge Provincial Park just north of Spuzzum, this steel-and-concrete suspension bridge spans the Fraser at the same spot as a colonial-era bridge of the same name. Completed in 1926, it provided the final link in the first highway between Coast and Interior. Prior to that, motorists from Coast and the Interior had been cut off from each other, unless they dipped down into Washington State or shipped their cars on railway flatcars.

A hefty toll was charged to cross the bridge until 1946, to the annoyance of truckers, ordinary motorists, and tourism promoters, but for nearly a quarter century, everyone who drove between Coast and Interior had to pass this way, sharing the same view of the river swirling and churning below. Replaced in 1961, it stands (for now) as a kind of monument to BC’s early car culture.

Clinton Hotel

Railways promoted BC’s natural scenery, not its history. The automobile, however, served as a kind of time machine, in that it allowed motorists to travel slowly and pause when and where they liked. Many were drawn to old buildings and other historical landscape features.

In the Cariboo, where drivers regularly imagined themselves following in the footsteps of gold rush-era freight wagons and stagecoaches, old roadhouses evoked romantic connections with yesteryear, and some were repurposed to serve the motoring public.

The most famous was the Clinton Hotel, built in 1861. It was a popular stopping place and the signature landmark for Clinton until May 1958. Unfortunately, it burned down the night after an authentic old-time stagecoach had been posed out front as part of BC’s ’58 Centennial celebrations. Today, its site has been marked by the Clinton Museum.

Wooden Head

Most of the 300-kilometre Big Bend Highway is underwater today, flooded by dams on the Columbia River. But when it opened in 1940 it was part of the Trans-Canada, and for 20 years was the main route between BC and the Prairies. It was never popular: a dusty, bumpy, six-hour drive through dense forests with few open views and even fewer buildings.

Travellers were welcomed to Boat Encampment – at the apex of the bend – by a giant wooden head perched beside the road, entreating them to drive safely so as to “enjoy the scenery longer.” This whimsical roadside colossus had been carved from a stump by a construction worker.

Wooden Head was the signature attraction of the lonely Big Bend Highway, and was retrieved after the Trans-Canada was rerouted through the Rogers Pass in 1961. Today it watches over traffic from a park in Revelstoke at the eastern foot of the Columbia River bridge.

Manning Park Gallows

The Hope-Princeton Highway provided motorists a choice in how to travel “beyond Hope.” It traversed Manning Provincial Park for nearly 80 kilometres, so when it opened in 1949, Parks Branch rangers scrambled to develop campgrounds, picnic sites, and attractions alongside it. They also sought to explain a major roadside eyesore: the Big Burn, where hundreds of acres of timber scorched in a forest fire lined the highway’s ascent to Allison Pass. Their solution was a roadside colossus that made the desolate sight into conservation lesson.

The Manning Park Gallows used shocking visual tactics to promote the gospel of fire safety, with a giant cigarette swinging from a noose, for the crime of killing BC forests. Park and Forest Service officials deemed this eye-catching pedagogical platform highly effective and erected it each summer until the Big Burn had turned green with new growth.

Columbia Village

Barkerville’s great tourism success during the early 1960s drove communities all around BC to propose similar attractions. Projects backed by the province and located beside a major highway achieved the best results – Fort Steele, for example. But not all of these schemes materialized.

The province supported the “Columbia Village” project proposed for Revelstoke, which would have seen dozens of old buildings salvaged and assembled into a heritage town. These buildings were due to be demolished for hydroelectric development on the Arrow Lakes. But finding a suitable parcel of land proved difficult. When the Keenlyside Dam near Castlegar was completed ahead of schedule, the desired buildings were destroyed and the project scuttled.

Revelstoke history enthusiasts were undeterred by the setback, and today there are multiple historical attractions in the area, including district, railway, and logging museums, plus Three Valley Gap heritage town.

Winner of the 2017 Lieutenant Governer’s Gold Medal for historical writing, awarded by the British Columbia Historical Federation, British Columbia by the Road: Car Culture and the Making of a Modern Landscape (UBC Press) by Ben Bradley challenges the idea that the automobile offered travellers the freedom of the road and a view of unadulterated nature.

In fact, an array of interested parties including boosters, businessmen, conservationists, and public servants manipulated what drivers and passengers could and should view from the road. When it came to roads and highways, planners and builders had two concerns: grading or paving a way through “the wilderness” and opening pathways to new parks and historic sites.

Ben Bradley is a historian of twentieth-century Canada. He is the author of articles about the history of parks, railways, and heritage sites in BC, and co-editor of Moving Natures: Mobility and the Environment in Canadian History.

[Cover images (counter-clockwise from top left): Cariboo Highway, Thompson Canyon, near Ashcroft, 1940s; Rogers Pass, 1960s; Hope, Welcome to Holidayland, with logging truck; Malahat Drive, 1910s; Vernon, Kalamalka Lake, 1950s.]