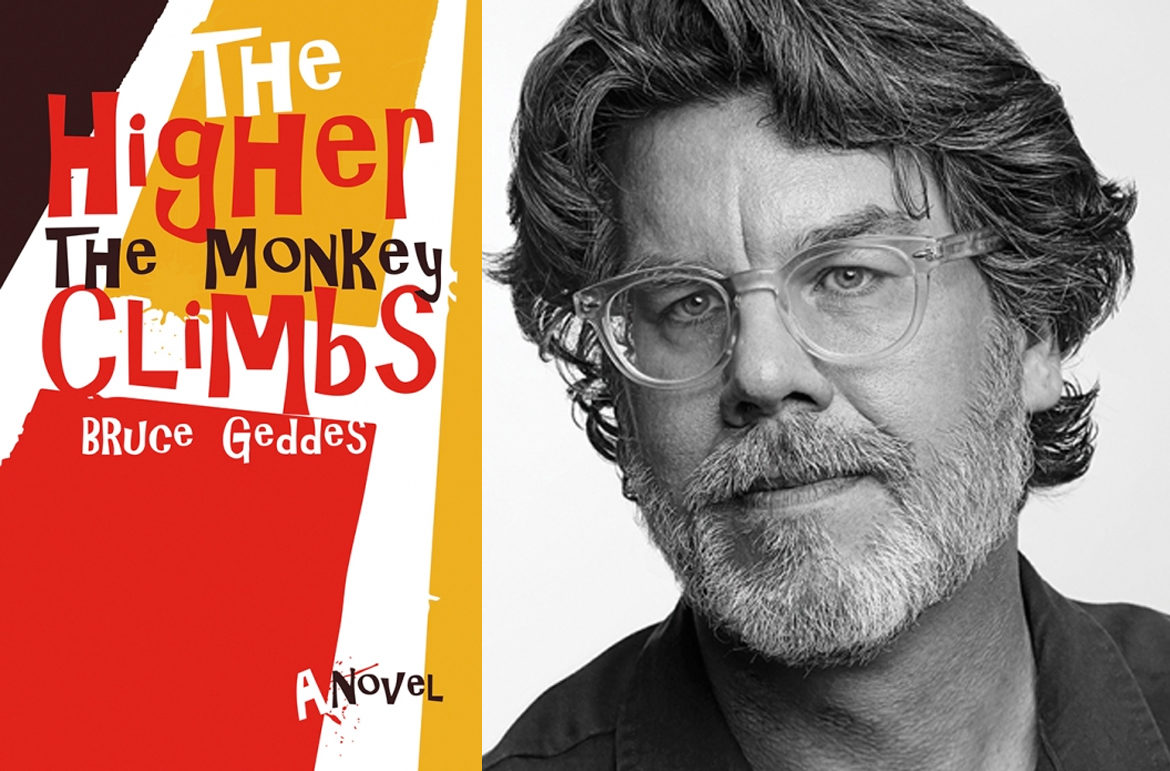

The Higher the Monkey Climbs opens with Richard receiving a call from his cousin Tony. Twenty-five years after Richard’s father died in a car accident, Tony is working on a theory that Gord’s death was orchestrated by Al Forzante, Gord’s former boss and a powerful union leader. With his own career and marriage sputtering, Richard is reluctant to believe Tony, inclined instead to cling to the one sure source of his own self-worth—being the son of legendary labour lawyer Gordon McKitrick. Does Richard believe Tony, pursue Forzante, and risk revealing unsavory elements of his father’s life? Or does he keep his mouth shut, humiliate his cousin, and allow Forzante’s crime to go unpunished? A mystery plated with plenty of sides, The Higher the Monkey Climbs by Bruce Geddes (NON Publishing) examines our relationship to our own pasts and how we adjust to the world as it shifts around us.

Although The Higher the Monkey Climbs is his debut novel, Bruce Geddes‘ fiction has appeared in various magazines and he has written two books for Lonely Planet. Bruce holds an MA in Latin American literature, is a graduate of the Humber School for Writers, and worked as a producer for the CBC.

How The Higher the Monkey Climbs start out? When did you realize the character you were writing was going to tell a larger narrative? Can you explain what interested you in the themes explored in your novel such as family loyalty, coming to terms with the past, and the fact that the narrator is an immigration lawyer?

The book was always a novel. The seeds of it lie in some chats I had over the years with a friend who’s been on the line at Chryslers in Windsor for twenty-something years. Anecdotes mostly, about the things that went on in the factory, how things have changed from one era to another. I started out thinking I could turn these stories into something, an updated, fictional Rivethead, maybe. But the more I worked that, the more it felt like a cliché about pretty much any industrial town. It felt like a poorly imitated Bruce Springsteen song.

Still, the relationship people have with the places they grew up and how that changes was (and is) pretty interesting to me. Not long ago, I was walking around with a friend of mine who now lives in Halifax but grew up in my current Toronto neighbourhood. He got a bit wistful, remembering things that had happened here or there, and I knew the feeling exactly. Your hometown gets in your DNA and, like some disease that lurks undetected, it stays there. Sometimes it emerges. Sometimes not. But it’s there. Anyway, that’s what got me on to writing about a guy living in Toronto who’s forced to confront some things from his past.

There was other stuff I was interested in, too. Like how people and organizations—in this case unions but it could be political parties, countries, charities, whatever—evolve and sometimes lose their relevance, even when they stay true to original values that were supposed to be eternal and universal. Everyone in the book is faced with a question of adjustment.

The idea of hanging on too long was also something I’d been thinking about; Alistair Forzante, the nonagenarian union boss, is modelled somewhat on Fidel Castro.

You’ve explored other mediums and genres in your previous writing. What was your biggest challenge in writing The Higher the Monkey Climbs?

Well, what wasn’t a challenge, really? Monkey is the second novel I’ve written.

The first one was a massive, sprawling, multi-generational thing involving a genius chef who poisoned her brothers’ food and neglected the daughter she only had to experiment with breast milk. The daughter marries a rich Greek guy, and they have a son who tried to get into Harvard Business School (but didn’t) and became an RA at the university in his hometown where one of the students stalks another and nearly freezes to death. Still can’t figure out why it didn’t sell.

So the challenges included reigning things in and concentrating my efforts so that less became more. The other big challenge was writing Tony and Richard, and that was really a question of spending a lot of time with them to learn about them and, I don’t know, make them more human.

For this novel, did you draw anything from your own experience in any way?

I produced interviews for one season of George Stroumboloupolous Tonight. That was actually really good training. You want to ask questions of your characters that will produce the most interesting answers in the same way you do for celebrities. After that year, I went back and made a lot of changes to the manuscript.

Also, I grew up in Windsor (which is called Wanstead in the book) and I knew people who were in unions, knew lawyers who dealt with them. I lived in Colombia for a year and so drew on that for Ines and Manolo. The scene where a crow perches ominously on a church hall balustrade really did happen to me in high school, and I once tried to cut vodka with Tang crystals. Some other stuff, too.

Who do you think will enjoy this book? What types of books do you think it’s similar to?

I’d like to think everyone would enjoy it. It’s wildly entertaining, you know! In fact, when I was writing it there was a lot of talk about the literary page-turner—Andrew Pyper’s name was mentioned a lot and if Gone Girl had been out at the time, it would have been mentioned in those conversations, too. I liked the idea of using the mystery of Gord’s death as a kind of backbone. The whodunit question is definitely important to the plot and it allowed me to branch off into other things. Structurally, I think it’s sort of like Gatsby where the narrator is tasked with sorting things out after the fact.