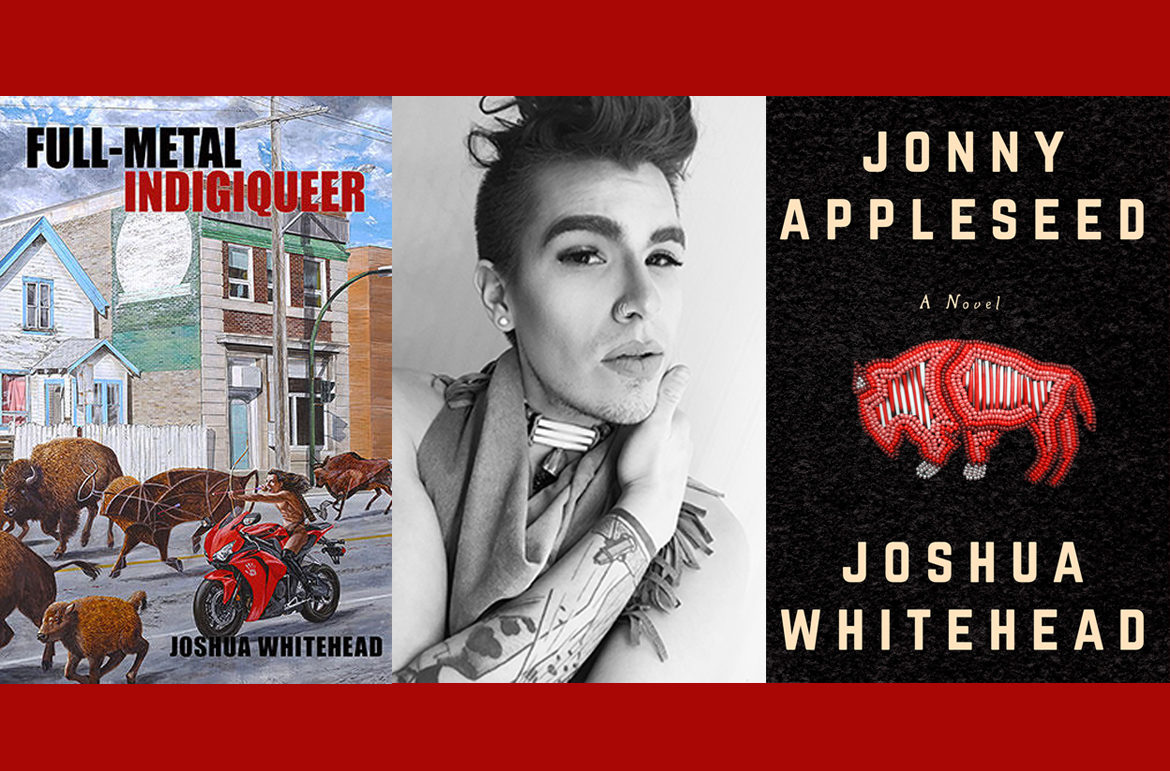

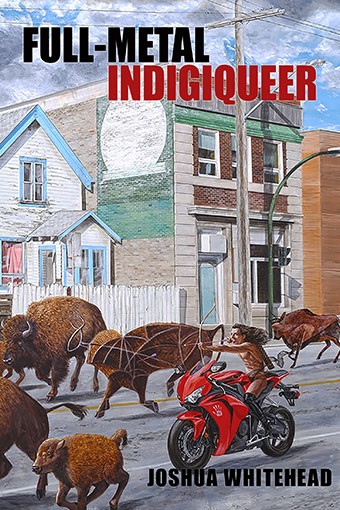

Joshua Whitehead‘s debut poetry collection, full-metal indigiqueer (Talonbooks), is a mashup of modern queer Indigenous life with cyberpunk dystopian elements. It tells the story of a hybridized Indigiqueer Trickster character, ZOA, who brings together the organic and the technological in order to re-beautify and re-member queer Indigeneity.

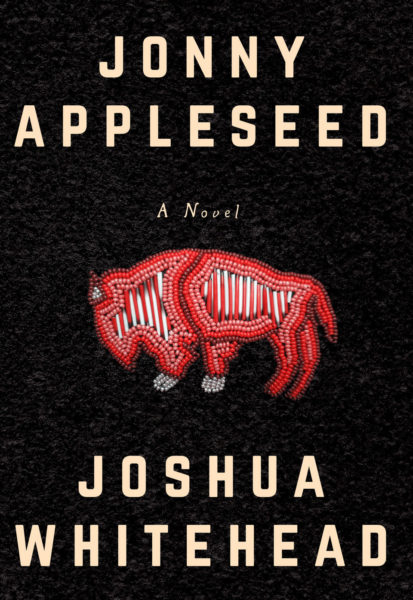

That same thread of repositioning queer Indigeneity is also apparent in Whitehead’s debut novel, Jonny Appleseed (Arsenal Pulp Press). Jonny is a Two-Spirit Indigiqueer young person (and proud NDN glitter princess) who must reckon with his past when he returns home to his reserve. Despite Jonny’s hardships around identity, belonging, and relationships, he is a strong example of fearless self-love that we all need. Whitehead recognized the need for a character like Jonny as there was a dearth of strong, Indigiqueer characters in the literature he was reading.

Joshua Whitehead is, in all senses of the word, a storyteller—otâcimow in Cree. Even in this interview, Whitehead weaves an incredible story of his influences, his hardships and triumphs, pop culture references, and his desire for visibility and accountability in the community.

What genre(s) do you write in?

I’m also very curious about what types of stories I tell. Surely, I’ve published and written literary criticism, theory, op-ed, non-fiction, autobiography, poetry, and prose—but what, I always ask myself, is the difference between the two? I think of Thomas King, who called everything “story”—I think of that root word in history, everything’s a curation of language, no? I ask what does genre mean in terms of gender, what does form mean in terms of the body, what does medium mean in terms of culture? For me, I call myself an otâcimow, a storyteller, because I don’t see any type of writing or genres existing in a vacuum. Everything is about animations, everything is about story—from Foucault’s jargon to Jordan Abel’s erasures.

Is there an experience, person or place that has had a strong influence on your writing?

My family, first, my homeland too influence me. I’m so lucky to have had a family that loves to sit down and tell story. If you ever sat around a dinner table with my family you’d be bombarded by stories, some hyperbolic (as in my mother constantly thinking my sister stole her remote and later finding it in the couch), some touching (as in animations of memories of our time spent together), some heartbreaking (recollecting ourselves after a death), and others enacting a powerful presence of what Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance,” (as in hearing about the trauma that’s riddled into our bones from residential schools to the 60s Scoop to CFS to MMIWG2S). This is why I can never think of myself as a solitary writer, I also don’t exist in a vacuum, I’m an otâcimow that’s an animated avatar of the stories that all of my relations, living, non-human, have shared with me.

But foremost, my niece Akira (who has the most bad-ass NDN biopunk name ever) centres a lot of my work. I world-build a little mound for that lovebug.

What is the hardest scene/poem you have ever written, and why was it difficult?

We need to see ourselves in healthy, respectful, beautiful, triumphant, sexy, and sexed ways—without it, we only see the Hyde in our Jekyll

There’s two that really hurt me when I wrote them. “mihkokwaniy,” the poem about my kokom who was murdered in the 60s and the intergenerational effects/affects that cost me and my family—every time I perform this poem I have to obliterate myself in some small way.

And Kokom in Jonny Appleseed who is an amalgamation of my two kokoms, my great-gran, and my aunties. Specifically, my aunt Terri who left us not that long ago. She was a bad-ass NDN woman who could crack rocks and split lightning with a stare but also laced her arms and laughs with love and maskihkiy (medicine).

I know that there isn’t often a single “ah-ha” moment, but what was the driving force behind writing full-metal indigiqueer?

I know that there isn’t often a single “ah-ha” moment, but what was the driving force behind writing full-metal indigiqueer?

full-metal was a project I worked on for the better part of five years while eddying my way through a BA, MA, and finally finishing it during the beginning of my Ph.D. The driving force was ZOA, my 2S cybernetic trickster, that old viral NDN-machina. ZOA is actually a character, a persona even, that I’ve held with me all my life. ZOA has been an orc in Lineage II, a Neopet, an online chat room avatar, a camp counsellor in Friday the 13th: The Game.

I’ve always been very attuned to logging myself into the cyberworlds with ZOA because I grew up as an overweight, femme-queer NDN nerd who spent his free time going to the library with his sister and discovering himself through MMORPGs (massively, multiplayer online role-playing games). ZOA’s allowed me to be femme, to morph between genders and sexes, to be sexy, to be vicious, to “pwn,” and also cared for me in many ways too. So I thought, let me materialize ZOA, lets put them in a book and let them wreck havoc on the texts that have harmed me, to etch out space where there wasn’t any for Indigeneity/2SQ (Two-Spirit, queer Indigenous) folx, let them heal me in that old role-playing way.

Your poetic style is anything but traditional, and full-metal indigiqueer opens with some very unique poems. How do you write and craft your poems?

I have this little game I play: find the hidden NDN. There’s almost always one, or a mention of one or a curation of an appropriated concept of Indigeneity in every text (I recently found one in Spiderman: Homecoming in the crumbling ruins of the Avengers’ alien technology). So when I was writing full-metal I played that while reading through the canons for my degrees, while playing video games and watching films, while listening to music and learning how to “beat” my face. When I did, I’d write down a feeling or a line that really stuck with me, resonated with me albeit angrily or lovingly, and I’d save it in my phone—call it an “anchor.”

All of my poems in full-metal, because I was so very much on the go and working to finish my degrees, are crafted from these anchors. I pull them out, kind of like a photograph, and with it, all of those feelings re-emerged even if it had been a week or a month since and the poem unfolded from there. Funny little things, those anchors, acting like seeds on the page and blossoming from a touch.

Your poetry collection provides so much for the reader to ruminate on, particularly its exploration of contemporary Indigenous identity. Can you tell me about how you see your use of deconstruction works as a means of decolonization?

When I think of full-metal, I think of the cyberpunk film AKIRA. Those technologically and bio-enhanced boys and girls all tested on, ridiculed, beaten, broken, dying. They had these abilities to destroy monuments, in full glory, and to rebuild from those ashes. I like that idea, to world-destroy in order to world-build and isn’t that the whole project of deconstruction in a postmodern literary and cultural epoch? What means “post” to Indigeneity? There is no post here, there is only the pre, circling in waves breaking the “A to Z” line that Western epistemologies like to think is time.

The short story “Jonny Appleseed” appeared in The Malahat Review’s Indigenous Perspectives issue (Winter 2016). Did you always plan for it to be a novel?

Little old Jonny, I love him so much—he’s the better parts of me all shiny in lube and medicine. Jonny was actually a character I created in my teenage years. I had this fantasy of writing a YA novel about these kids in Selkirk, Manitoba who called themselves the “concrete poets”. This group of kids read as a trace but living as a triumph.

I think of full-metal indigiqueer and Jonny Appleseed as companion pieces; Jonny and ZOA, that old star cross, condom-studded, love story.

While I was writing full-metal I continually had this human character who would converse with ZOA (as in the beginning poems) and then quickly fades away as the narrative becomes a sort of re-augmented NDN cyborg/biopunk that just goes full-on wihtiko and eats and eats and eats all the while excreting new territories, new places to storytell, leaving little shards of spiritstory. The human speaker though, for me, was Jonny. This little queer boy logging in and unleashing a virus into these canonic mainframes. So I wrote a short story about him (the bits in The Malahat), then he became a 100-page novella here in UCalgary’s English department, and then he became a novel after I spent a week in the Banff Leighton Artist Residency (an award gifted to me from a poem in full-metal).

He just kept growing and growing in the spaces that, I think, ZOA opened up for him. So I think of them as companion pieces, Jonny and ZOA, that old star cross, condom-studded, love story.

What challenges have you encountered in your journey as an author and what helped you overcome them?

The biggest challenge was thinking I had to read and write as white. It wasn’t until my Ph.D. (after creating a directed reading) where I actually got to study Indigenous literatures in a nuanced and meaningful way. I was force-fed, like a glutton, the canon for so long; ingrained to think that writing is a suffering, writing is a solitary act, writing is a type of voyeurism.

I overcame them by being a rebellious reader, a resistant one, and reading against those stories (re: full-metal) as well as taking time for myself to listen, for many years, to Indigenous storytellers, writers, elders, and kin. It was Eden Robinson who once said that “If you don’t see yourself in the literary landscape, then the landscape needs you more than anyone.” When I heard that, it was a major turning point for me—Eden was right, I didn’t see myself and that energized me to break all the rules so I could write myself into the world.

We need to see ourselves in healthy, respectful, beautiful, triumphant, sexy, and sexed ways—without it, we only see the Hyde in our Jekyll, we don’t see much past our traumas and its presents.

Jonny Appleseed often pushes normative notions and addresses difficult topics. But the writing seems so fluid and appears effortless. How do you balance this as a writer? Is including these “taboo” subjects important for you as a storyteller?

Jonny Appleseed often pushes normative notions and addresses difficult topics. But the writing seems so fluid and appears effortless. How do you balance this as a writer? Is including these “taboo” subjects important for you as a storyteller?

In Memory Serves, Lee Maracle wrote that “Sometimes our humour is used to open up people to hard truths.” I very much agree, sometimes I think that when an Indigenous laugh is also a type of salve being reapplied over old wounds. I see this working so beautifully in Eden Robinson’s Son of a Trickster (I once told her at a reading that my protagonist Jonny was in love with Jared, hah), I see this in Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves, Katherena Vermette’s The Break, Tracey Lindberg’s Birdie, and in Billy-Ray Belcourt’s This Wound is a World to name a few.

I think there are a lot of preconceptions around what is “too dark” or what is non-applicable to youth in order to maintain this idealization of a “childhood innocence” (that I always read as whiteness with its privileges) where children and youth should undergo this type of metamorphosis where you learn about the harder parts of the world in a timely and acceptable fashion.

But for Indigenous youth, we don’t follow that same timeline. When I worked for the Selkirk Friendship Centre I once had a thirteen-year-old overdose on my desk; I think about my father taken from his family and community as a young child; I think about Wenjack being reanimated continually. What does “childhood” and “innocence” mean for Indigeneity? I don’t want to think that Indigenous childhood died in those schools. But, we do age in a different time zone, and through location seemingly a different dimension too, as compared to the innocence of those protected children (think here of Reverend Lovejoy’s wife screaming “Won’t somebody think of the children?”). That’s what I wanted to do, to bring these “taboo” subjects to the conversation, to the metaphorical dinner table, and lay them out.

I wanted Indigenous youth to see themselves in Jonny Appleseed and know that they’re worth and lovely and beautiful even in their pain too. We do a disservice to ourselves and to our youths by censoring these topics, especially re: sex, sexuality, and gender. I wanted to break a piece of me off and share that with them because I would have wanted to have seen that as a kid too.

You recently withdrew from the Lambda Awards. Your honesty and transparency set an incredibly positive example for others. Why was issuing a public statement important to you?

I wanted to be accountable because that’s what I think literature is about. I also wanted to be transparent, to set a precedent, because I need to put my actions into play too.

I consulted a lot with my community and kin about my Lambda. I was so honoured and to have my first book be recognized on such a large scale was humbling beyond belief. But that particular title wasn’t mine to take—the trans community deserves that title for the hard work, perseverance, love, sweat, tears, and blood they’ve had to sacrifice to even have that nomination.

I wanted to be accountable because that’s what I think literature is about. I also wanted to be transparent, to set a precedent, because I need to put my actions into play too. Theory is good and everything but it’s only as strong as its applications. Hopefully, one day there will be a 2SQ categorization there and you know mama is going to come decked to represent.

What is the one book that you wish you wrote, and why?

I don’t think there’s any books that I love that I could have written—those are biostories owed to the communities and peoplehoods they come from. But, if I could have consulted or collaborated with a certain text it would have to been with Richard Van Camp’s The Lesser Blessed. That book opened me up to a world of Indigenous youth and the vivacity of it all in its wondrously pained vibrations. It’s an absolute must-read (and Larry Sole also makes a small cameo in full-metal as a shout out so I feel I got to talk with him a little bit at least, hah).

Where do you like to take a book and read? (favourite spot in the city, or in the world?)

Literally, my bed. I need to be removed from noise pollution and company when I’m reading so I can listen to my thoughts and feel what I need to feel. Plus I like to nap with stories too, hah.

What books are you reading? Can you give us a recommendation (or a few)?

I just finished reading and teaching Robinson’s Son of a Trickster. I’ve been talking non-stop about Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves. I just had some lovely conversations with Vermette’s The Break while I was at home.

But two that really stuck with me after hearing both author’s speak while I was at NALS (the Native American Literature Symposium) in Minneapolis this last month was: Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem and Natalie Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec.

Do you listen to music while you write? If so, what sort?

Non-stop, I need white noise to concentrate enough (or else I end up looking at RuPaul’s Drag Race’s Reddit page, researching how The Walking Dead universe would have blossomed if Carl hadn’t died, or watching another makeup tutorial, hah).

I listened repeatedly to Tanya Tagaq while writing full-metal indigiqueer—I needed those haunting growls. Buffy Sainte-Marie comes up a lot on my playlist as does Jeremy Dutcher now after having heard him during the New Constellations tour.

While writing Jonny Appleseed I listened to round-dance music a lot, spliced with Justin Bieber, Logic, Amy Winehouse, Cardi B, and Janelle Monáe. I felt like I really needed to get into his headspace—sometimes I think of character crafting as method acting.

Show us your writing space— what do you surround yourself with when you write?

Joshua Whitehead is an Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit storyteller and academic from Peguis First Nation on Treaty 1 territory in Manitoba. He is the author of full-metal indigiqueer (Talonbooks, 2017) and the winner of the Governor General’s History Award for the Aboriginal Arts and Stories Challenge in 2016. He has been published widely in Canadian literary magazines such as Prairie Fire, EVENT, Arc Poetry Magazine, CV2, Red Rising Magazine, and Geez Magazine’s Decolonization issue. He is currently working on a non-fiction, critical manifesto and a PhD in Indigenous Literatures and Cultures at the University of Calgary (Treaty 7). Jonny Appleseed (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018) is his debut novel.