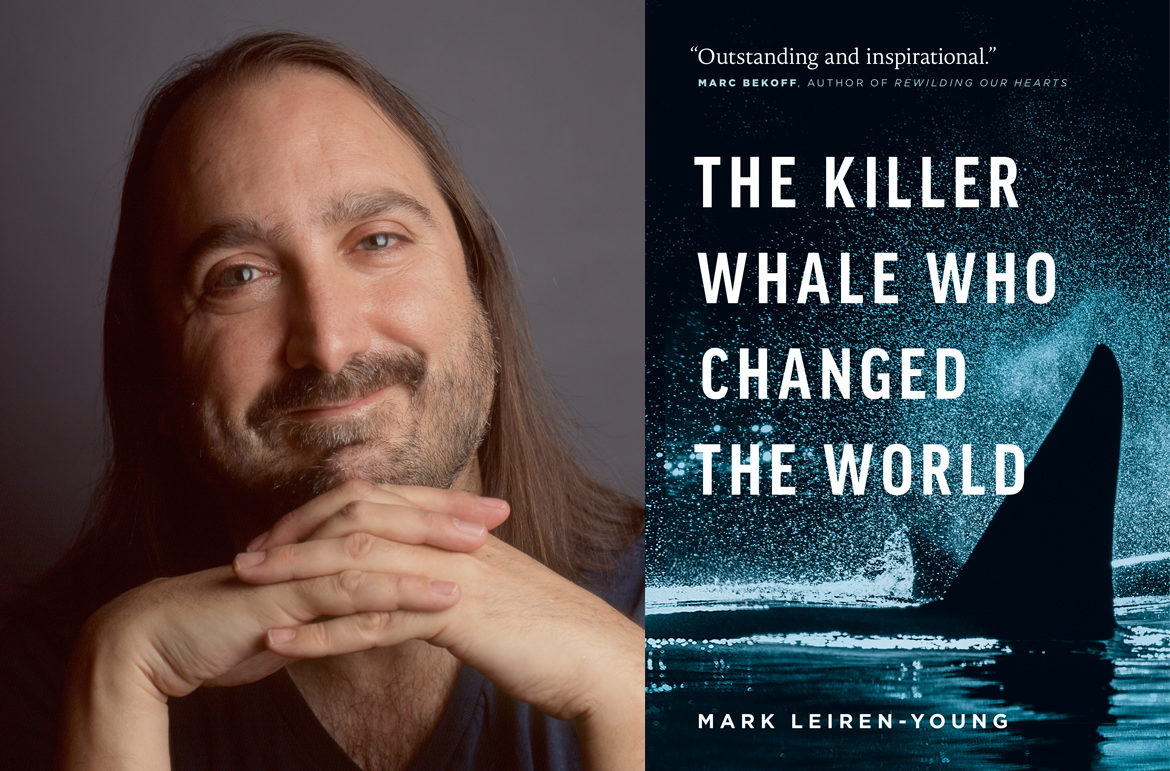

The Killer Whale Who Changed The World by Mark Leiren-Young (Greystone, 2016) is a fascinating and heartbreaking account of the first publicly exhibited captive killer whale—a story that forever changed the way we see orcas and sparked the movement to save them. Read Local BC caught up with Mark to discuss his interest in Moby Doll, and subsequent orcaholism.

You first heard about Moby Doll in 1996. How did you learn about his story?

I was writing a story for Maclean’s Magazine and Paul Watson—the founder of the Sea Shepherd Society—told me that the Vancouver Aquarium was the first place to ever display a captive killer whale. I couldn’t believe I didn’t know this, couldn’t believe everyone didn’t know this. I was hooked.

Moby Doll was the first orca publicly exhibited in captivity. But the original intention was to kill one to create an anatomically correct statue. Why and how did this killer whale come to be captured?

The Vancouver Aquarium sent out a team to kill a killer whale. Everyone knew it would be crazy to capture one – they were far too deadly – but when the amateur harpoonist finally took his shot, he missed. Sort of. Instead of killing the whale he accidentally hooked it. And the rest… changed the world.

Previously, orcas (or killer whales) were seen as violent predators—monsters. How did the capture of Moby Doll change that?

Within minutes of the harpoon hitting Moby things began to change. Many people believed that killer whales were so blood thirsty that – given the chance – they would rip each other to shreds. But when Moby lost consciousness two larger killer whales came to his rescue and held him aloft so he could breathe. When the hunters saw this, they no longer wanted to do what they’d been hired to do. Instead of finishing off the wounded whale with the rifle they had—for that exact purpose—they called their boss at the aquarium and asked if it was possible to change the plan and either display—or free—the whale instead. And then Moby arrived in Vancouver and everyone was shocked.

But this capture also spurred another major change—a sort of maritime gold rush for public aquariums to capture and display live whales. What happened, and what were the implications for this?

We went from killing whales with bullets to loving them to death. Before anyone realized how small the population was, orca rustlers took out almost an entire generation of young orcas from the Salish Sea.

Moby Doll inspired a whole generation of scientists to learn more about how these magnificent creatures, and also sparked the movement to save them.

What’s the current status of orcas in the wild right now?

There are orcas in every ocean on the planet so orcas—as a whole—are everywhere. What we know—because of the research sparked by Moby—is that there are different and distinct ecotypes of orca (basically different species). Moby’s family—known as the Southern Residents—is a seriously endangered population with fewer than 80 orcas still out there. And their culture—and that’s not a word I use lightly—is completely unique.

In Canada, the orcas are facing a terrifying new threat. I’ve spoken to scientists who believe the recently approved expansion of the Kinder Morgan pipeline equals extinction for the Southern Residents. I shared this in a recent speech to a federal government panel that toured BC (to create the illusion that the the KM proposal was actually up for debate).

What research did you do for this story? Did you learn anything that surprised you?

I’ve researched this story since 1996 and the biggest shock for me was also one of the biggest shocks for scientists. There are only three creatures on the planet where females have an extended life beyond their reproductive years. Humans, orcas and pilot whales (who are closely related to orcas). The theory—known as “the grandmother hypothesis”—is that in these three species wisdom is more important to the survival of the species than reproduction. The implications are mind-boggling and, to my mind, beg the question, what moral right do we have to harm these creatures?

Your article for the Walrus about Moby Doll was a finalist for the National Magazine Award, and you won the Jack Webster award for his CBC Idea’s radio documentary “Moby Doll: The Whale that Changed the World”. What is different about telling the story in book format?

The big difference is that as an author I really felt like i had to get a handle on all aspects of the story. The Walrus feature was only 3000 words and tightly focused. The radio doc—and I LOVE radio is built around quotes where other people explain the story. The book required me to become an authority aka author. It’s much easier to quote other people…

I hear you’ve finished a feature length film documentary about Moby Doll.

I was working on the documentary because I felt that someone had to preserve this story for posterity. So the documentary was in the works over a year before the book was. I’d always dreamed of writing a book about this story, but I’d had no luck pitching one and had surrendered on the idea. Then, the night Moby won the Webster, Rob Sanders from Greystone said we should do a book.

The challenge with historical documentaries is licensing historical footage—which is very expensive. I’ve shot all the interviews I need, but we need someone to cut us a cheque so I can buy the footage I need from CBC and the NFB. Meanwhile, I’ve made a short doc about one of Moby Doll’s relatives—Granny, The Hundred Year Old Whale. Granny’s movie should be in festivals this summer and is narrated by actress and activist, Laura Vandervoort (Bitten).

What are you working on next?

For BC readers who are also BC theatregoers my play Shylock is back at Bard on the Beach in September and my new play, Bar Mitzvah Boy, debuts with Pacific Theatre in Vancouver next March. I hope I’m only a few weeks away from announcing my next book so… stay tuned for that. And yes it’s about orcas.

P.S. Mark wasn’t kidding about loving orcas and radio… he’s just launched Skaana, a ‘pod’cast about orcas and oceans.

Mark Leiren-Young is a journalist, filmmaker and author of numerous books, including Never Shoot a Stampede Queen, for which he won the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour, and The Green Chain, which is based on his award-winning film of the same name. His article for the Walrus about Moby Doll, the first orca publicly exhibited in captivity, was a finalist for the National Magazine Award, and he won the Jack Webster award for his CBC Idea’s radio documentary Moby Doll: The Whale that Changed the World. Leiren-Young is currently finishing a feature length film documentary on Moby Doll.

One reply on “Mark Leiren-Young: self-professed orcaholic and the whale who inspired him”

Do elephants, another matriarchal society, also have post-menopausal females?

When will Mark’s plays be performed in Victoria?