North America is in the grips of a drug epidemic. While deaths across the continent soar, Travis Lupick‘s new book explains the concept of harm reduction as a crucial component of a city’s response to the drug crisis.

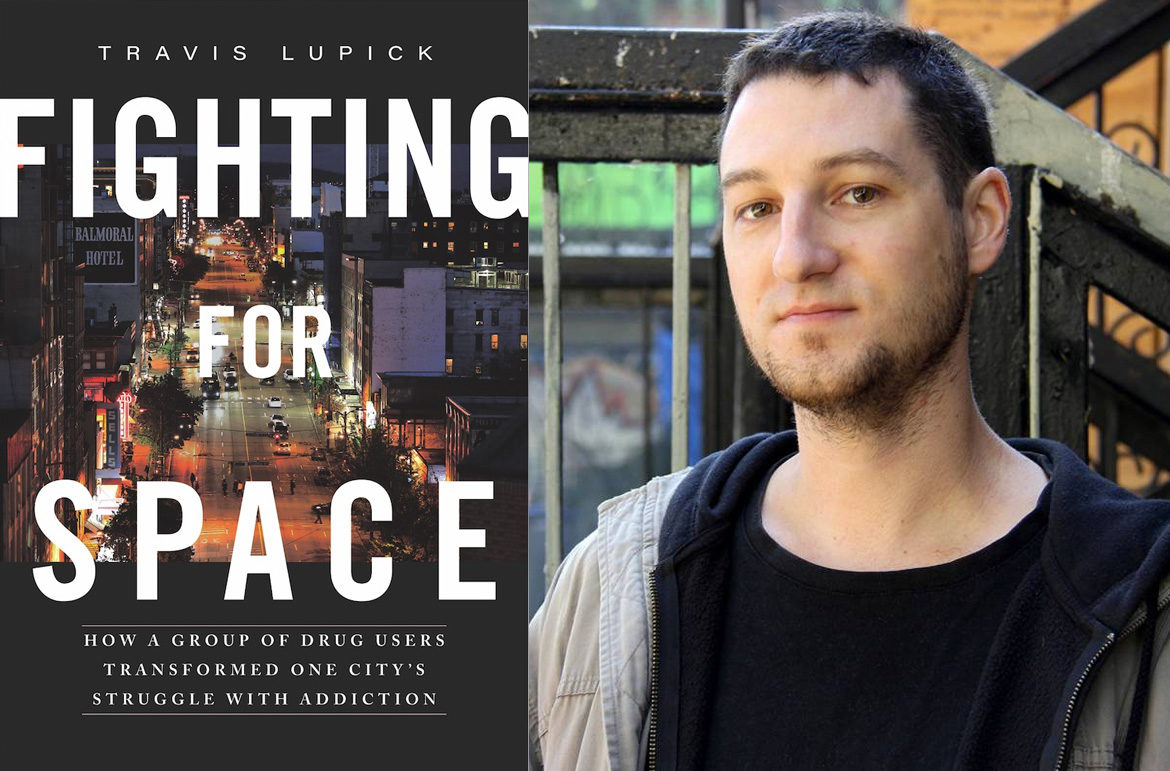

Fighting for Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City’s Struggle with Addiction by Travis Lupick (Arsenal Pulp Press) is the story of a grassroots group of addicts in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside who waged a political street fight in the 1990s and 2000s to change how the city treats its most marginalized citizens. As the same overdose crisis patterns emerge in cities across North America, there is much that advocates for reform can learn from Vancouver’s past experience.

Chapter 4: Hotel of Last Resort

Excerpt from Fighting for Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City’s Struggle with Addiction by Travis Lupick (Arsenal Pulp Press)

The Portland Hotel is located on the southeast corner of Carrall and East Hastings streets. The hotel shares the intersection with Pigeon Park, a small collection of benches screwed into a concrete space with a couple trees hanging over them. An open-air drug market operates there, and the benches make it a popular spot for the neighbourhood’s homeless people and alcoholics.

The hotel itself was built in 1908, and when Evans took the keys in March 1991, that was apparently the last time anyone had bothered to give it so much as a fresh coat of paint. Vancouver’s old cable-car line once ran down East Hastings, making the hotel a prime location in the early twentieth century. But those days had come and gone. The Portland was now a slum; paint peeled off the walls, the pipes leaked, the floor was filthy, and the lighting was dim. The Portland’s tenants were only there because it was one step better than living on the streets.

“We ended up being known as the ‘hotel of last resort,’” Evans remembers.

On paper, Evans’s job was to support ten of those tenants who were diagnosed with severe mental-health issues. In fact, the entire hotel was hers to run as she saw fit. “To start, I focused a lot on practical things: vacuuming and cleaning, changing door locks, and trying to figure out how to paint a room and hang curtains,” she recalls. “I did everything from cleaning to personal care to helping people with their welfare workers or whatever issues people had. It was absolutely, completely overwhelming.”

There were a lot of empty rooms in the hotel, so Evans also began to fill them up, taking people in off the street who were blacklisted from everywhere else. After just a few weeks, Evans was responsible for sixty or seventy people. “People who came with mental-health issues, HIV, criminal histories, and drug use,” she says. “That is who needed the support.”

Outside of the hotel, the Downtown Eastside was just as beat-up as the building Evans was given.

In British Columbia, welfare cheques are issued on the last Wednesday of every month, so once every four weeks, the Downtown Eastside is flooded with cash. Drug dealers circle the banks like sharks, looking for anybody with an outstanding IOU and potential customers who can rack up new debts. Government officials call it “Welfare Wednesday.” Residents of the Downtown Eastside call it “Wely” or “Mardi Gras.”

Liz Evans remembers her first Welfare Wednesday working at the Portland.

On the ground floor of the hotel, just around the corner from her office, there was a rough bar called the Rainbow. “The bartender was a big guy who kept a baseball bat behind the counter,” Evans says. “On my first welfare day, he smashed some guy’s head open with that bat. Someone came screaming into the hotel to get me. I went running out—I remember, I was wearing the most inappropriate clothing, a cotton skirt and my hair in pigtails.”

The man lay on the sidewalk with his skull broken open. “I’m holding this guy’s brain in, and there’s blood everywhere, all over my skirt. I remember waiting for the ambulance to show up, wondering if he was going to live or die,” Evans recalls. “It was just one of those moments,” she adds. “What the fuck am I doing in the middle of all of this? Holy shit.” It was May 1991, and Evans was twenty-five years old.

“He was a Hispanic drug dealer, was what I was told,” Evans continues. “But as far as I was concerned, he was another drug user. That’s one of so many stories that illustrates the hatred of people who used drugs in the community, not just by the outside world, but by people in the community too. Drug users were seen as scum.”

In the early 1990s, the Downtown Eastside’s drug scene was blowing up. The city had begun a slow but sustained effort to thin out a concentration of bars in the Downtown Eastside that had come to give it a rough edge. But closing the bars had the unintended consequence of pushing some people into drugs and creating room for that market to grow. Around the same time, injection cocaine arrived on the scene.

Everyone who lived at the Portland was severely addicted to drugs or alcohol. Evans estimates that ninety-five percent were injection users. “They were treating themselves badly and treating each other badly because they didn’t feel like their lives were worth much,” she says. “I was getting to know people and listening to their stories. And always the common denominator was, ‘My life is worth shit and I don’t matter.’ That was the piece that really made me think about my mum and think, ‘Well, fuck, these are just people in the world who don’t feel like their lives have a right to occupy space.’”

While she was never abused, Evans saw her own life in the lives of her tenants. “I had grown up with a mentally ill mother. I never had thought of her as sick; I just thought she was a really nice person who was broken and sad,” she explains. “And so I just saw [the Portland tenants] as broken and sad. These people are lovely, but they don’t fit. For whatever reason, there is no space for them. They don’t fit anywhere in the world, and the world, to them, feels like a very unwelcoming place.” Inside the Portland, she worked to create a sanctuary.

Travis Lupick is holding a book launch and panel discussion on November 16. The evening will begin with a short performance of Illicit: Stories from a harm reduction movement. The theatre production shares the stories of DTES residents who are working on the front lines of the community’s response to the overdose epidemic.

The panel, “The Fentanyl Crisis and Where We Go From Here”, brings together a politician, a mother and advocate, a nonprofit service provider, a representative for the health-care system, a drug user, and a journalist, for a public discussion about BC’s fentanyl crisis.

One reply on “Drug epidemic and overdose crisis looms large in Fighting for Space by Travis Lupick”

This is exactly the sort of thing I need to get involved in. I’d love to branch out meet new likeminded people. I’m always looking to expand my knowledge so I can better help others. I’m freshly new to the blogging website world and would benefit from other points of view and opinions.