A beautifully illustrated children’s story about Canadian wildlife, Alison’s Fishing Birds (Caitlin Press, 2017) is the story of a young girl’s encounter with some of BC’s most intriguing river birds.

Written by acclaimed Canadian conservationist and Governor General Award-winning author, Roderick Haig-Brown, the story is richly illustrated by acclaimed and talented artist Sheryl McDougald with linocuts by Jim Rimmer. Alison’s Fishing Birds was first published as a limited edition in 1980 by Colophon Books.

Enjoy an illustrated excerpt below.

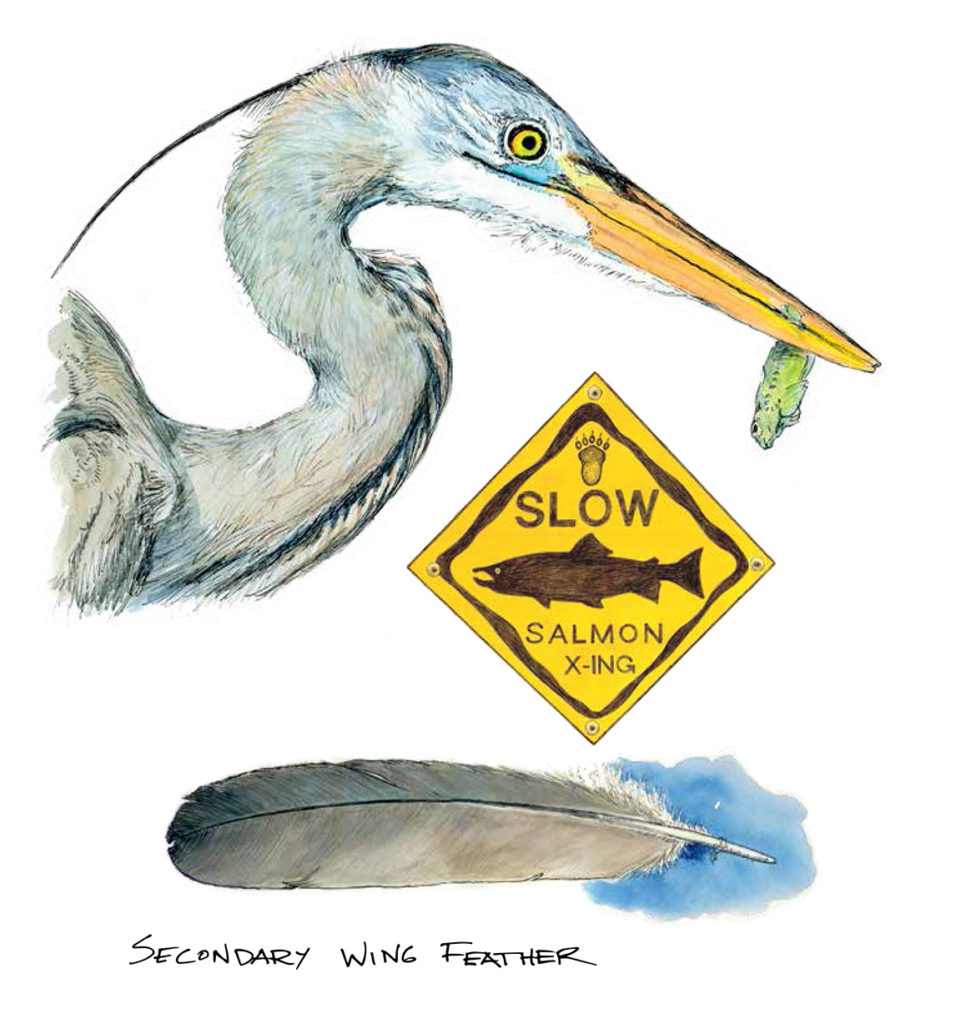

The Heron

Perhaps the most skilful of all the fishing birds that lived near Alison’s house were the herons. Alison saw them almost every evening as they flew up the river on slow, wide wings from a day of feeding along the beaches or on the flats at the mouth of the river. She liked them because they were so slow and calm and dignified, and because they were so big. Standing on their long legs and with their long necks held straight up, they were taller than Alison herself, and she was quite a tall little girl for her age. The spread of their wings was as great as the height of Alison’s father and he was a tall man.

One day Alison was walking down the trail toward the mouth of the river, to go and play with another little girl who was a friend of hers. She stopped at one place where she could walk out along a pile of rocks, because sometimes she had been able to look into the water and see little fish from there. Just as she started to go out on the rocks she saw a great shadow slipping over the ground, so she stopped at once and stood very still, looking up at the big heron who had made the shadow. He did not see her at all, because she was still under the trees, and he pitched down gracefully at the edge of the water.

He was so close that Alison could even see the black pupil of his eye. He was a very splendid bird, much more splendid than she expected because she had always seen herons in the distance before and they looked just grey. This heron—Alison called him old Walk-up-the-Creek to herself, because some people call all herons that and somehow the name seemed to fit this one—old Walk-up-the-Creek had a grey back all right, but he had much more than that. His long bill, as strong and sharp as a sword, was yellow. His head was white and two long dark plumes curved back from it. His throat and breast were white, but speckled handsomely with light brown. There were more plumes on his throat and on his back, and altogether he seemed a magnificent bird.

Alison had time to see all this because he stood quietly at the edge of the water, on one leg with the other drawn up under him, for several minutes. Then he began to walk, very slowly and smoothly, out into the water. It was quite shallow and soon he stopped again and stood quite still, on both feet this time. His neck was drawn in so that his head was hunched between his shoulders; but his great strong beak was pointing down a little and Alison could see that he was looking hard down into the water.

He stood so long like that that one of Alison’s feet went to sleep and she wanted to scratch her nose and wanted to pull her dress down a little on her shoulder, where it was uncomfortable. But she didn’t move because she knew old Walk-up-the-Creek was going to catch a fish and she wanted to see him do it. And all at once he did it, so quickly that Alison hardly saw how, though she was watching all the time. His head seemed to jump forward, his long beak went down into the water and out again in the tiniest part of a second and there was the fish, held so firmly that it hardly wriggled at all.

For nearly a minute old Walk-up-the-Creek didn’t seem to pay any attention to the fish in his beak; he simply stood there looking just as he had before he caught it. Then he lifted his beak, put his head back and swallowed the little fish, and Alison could see a ripple as it slid all the way down his long neck.

As soon as the little fish was out of the way old Walk-up-theCreek began fishing again. This time he held his head forward a little more and his body was tilted forward too. And instead of standing quite still he walked forward through the water, but so slowly that it hardly seemed like walking, though Alison couldn’t think what else to call it. He lifted first one foot, then the other, so slowly and gently that it really seemed as though he wasn’t moving at all. And quite suddenly his beak darted down again and Alison saw he had caught another fish.

This time he swallowed it more quickly and, just as he was starting to fish again, Alison’s nose tickled so much that she sneezed. Old Walk-up-the-Creek didn’t wait to see that it was only a little girl. He flapped his great wings, squawked angrily and flew heavily away. Alison watched the little ripples on the water where he had been standing and felt sorry she had frightened him so much. But she had to go on and play with her friend and couldn’t wait for him to come back.

That evening just before dark, when Alison was back at her own house again, she saw a heron flying up the river towards the big trees where they always roost. He was a fine big heron and Alison watched him carefully, wondering if he was old Walk-up-the-Creek. His broad dark wings moved very slowly; his long beak was pointing sharply straight in front of him, his head was hunched back between his shoulders; his thin legs were stiffly together, held straight out behind him.

Alison couldn’t see his plumes or the white of his head and breast; he was just grey and big against the sky. But as he flew past her he croaked loudly, just once. The herons don’t generally croak when they are flying up past the house in the evenings, so Alison knew it must be old Walk-up-the-Creek, and he must have remembered her.

Excerpt from Alison’s Fishing Birds by Roderick Haig-Brown, illustrated by Sheryl Macdougald with linocuts by Jim Rimmer, and foreword by Andrew Nikiforuk, published with permission from Caitlin Press (2017).

Excerpt from Alison’s Fishing Birds by Roderick Haig-Brown, illustrated by Sheryl Macdougald with linocuts by Jim Rimmer, and foreword by Andrew Nikiforuk, published with permission from Caitlin Press (2017).

One reply on “The Heron: an illustrated excerpt from Alison’s Fishing Birds”

Thank you, Read Local BC!! 🙂